Review: A Korean Hawaiian American dream (with Guy Fieri) goes pear-shaped in an inventive debut

On the Shelf

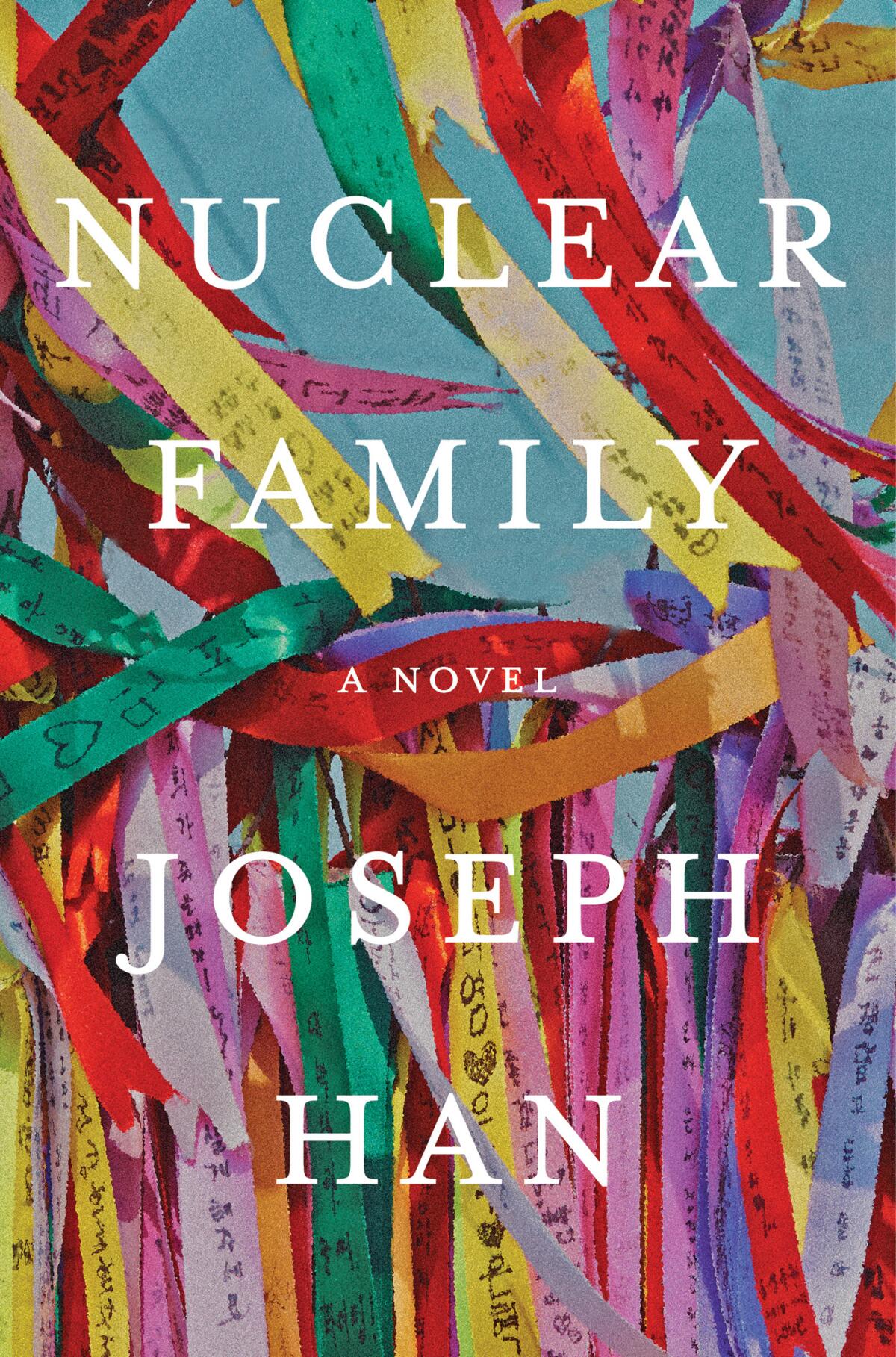

'Nuclear Family'

By Joseph Han

Counterpoint: 320 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Two historical facts: The armistice agreement that still governs the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea was written by an American military attorney in 1953. And the agreement that declared Hawaii the 50th state was written by continental Americans in 1959.

If, in the 20th century, we didnât interrogate such facts, thank goodness things have changed. Joseph Hanâs debut novel, âNuclear Family,â tells not only the story of a Korean American family living in Hawaii but also a story-within-a-story about how that Korean American family was broken into pieces by the 1953 Korean divide.

At first, the Cho family â Appa, Umma, Grace and Jacob â bears a superficial resemblance to the store-owning immigrants in the popular Canadian sitcom âKimâs Convenience.â Yet they are both more affluent and less connected than that TV family; they own three plate-lunch delis in Honolulu, but Grace spends her university days in a weed-soaked haze, while closeted Jacob jets off to Korea to teach English, hoping to make peace with his sexuality in his grandparentsâ homeland in a way he hasnât been able to in his own.

While in Seoul, Jacob is first stalked and then inhabited by his dead grandfather, Baik Tae-woo, who left his first family behind the DMZ during the Korean War. Tae-wooâs will is so strong that, when Jacob is on a tourist outing to view the border, his grandfather tries to bang through a spirit wall and Jacob trips, landing on his face, his head crossing the border â pratfall as international incident. Han is very funny both in small moments (Appaâs regular dances while sweeping the shop) and larger ones (Tae-woo manipulating a drunk Jacob into a mĂŠnage Ă trois).

Bethanne Patrickâs June highlights include Tom Perrottaâs âElectionâ sequel, essential new war histories and a fresh look at females of all species.

That plot summary would make for a terrifically mordant comic novel, but Han is so skillful in his debut that it becomes much more than one familyâs hapless attempts to cope with their sonâs dilemma and the media blitz that threatens to ruin their chain business. Yes, Grace and Jacob are alienated from their parentsâ industry and family piety, as well as from each other (âa distance had grown and set in place, a permanent fissure the width of the hallwayâ). But the novel really gets going when that alienation slithers out from their stories into the streets of Honolulu, where not everyone feels at home.

Itâs Hanâs attention to âthis monstrous city,â with its traffic and noise and constant military presence, that sets his Korean American family story apart from some others recently published. First, thereâs the constant friction between Koreans and Korean Americans and the other populations in the city; the Chos partly owe the success of their business to one of the whitest white men in food culture, Guy Fieri. Han poses Fieri, a man whose approbation of âfoods people love with all their hearts, at the expense of those same hearts,â as the Cho familyâs strange commercial savior, his fiery face adorning their establishments.

But in the wake of Jacobâs DMZ kerfuffle, the customers who gobbled up meat jun and mac salad and numerous banchan start to keep their distance. The media surmises that Jacob might be a Korean spy. Once his family is linked to the North Korean regime, Appa learns that loyalty looks different in his adopted country.

Itâs that tension that gives âNuclear Familyâ its radioactive fuel: between traditional values in both Korea and Hawaii, between all traditional values and the mores of American capitalism. Early on, the author focuses on the generation gap among the Chos. But somewhere in the middle, Hanâs writing becomes experimental â particularly in a section written by Grace full of âredactionsâ that invites the reader to play an existential variation on Mad Libs. If you can freely substitute words, why not people?

Showrunner Soo Hugh and directors Justin Chon and Kogonada find the personal amid the storyâs sweeping scope

The last third of the book grows more and more fragmented, as Han picks up the pace in explaining how Jacob and Baik Tae-woo âmetâ and started sliding in and out of each otherâs bodies and consciousnesses. A chapter titled âLocals,â told in the second person, insists on the connection between Koreaâs U.S. military presence and Hawaiiâs U.S. monetary presence.

âWe came to Hawaiâi from other countries and worked under an exploitative plantation system,â says Hanâs collective immigrant voice. âWe came as picture brides, plantation laborers, bachelors, families. Most of us felt like we didnât have a choice in the matter.â Later, Han acknowledges that these immigrants âdonât speak âĂlelo Hawaiâi. ... We know Kamehameha schools are only for the Hawaiian kids, but we make do and embrace all the islands have to offer us.â

If youâre not struck by these sentences, maybe you havenât been paying attention to the history of all the United States, where Indigenous languages have disappeared and the children who speak them are shunted off into reservation schools even as their usurpers embrace all the country has to offer. We have more in common with the Chos than ambition and generational drift.

In âNuclear Family,â through laughter and wonder and intriguing complexity, Han makes us pay attention.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

Juhea Kimâs âBeasts of a Little Landâ captures the dualities of Korean history but ties up symbols too tightly in the service of grand ambitions.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.