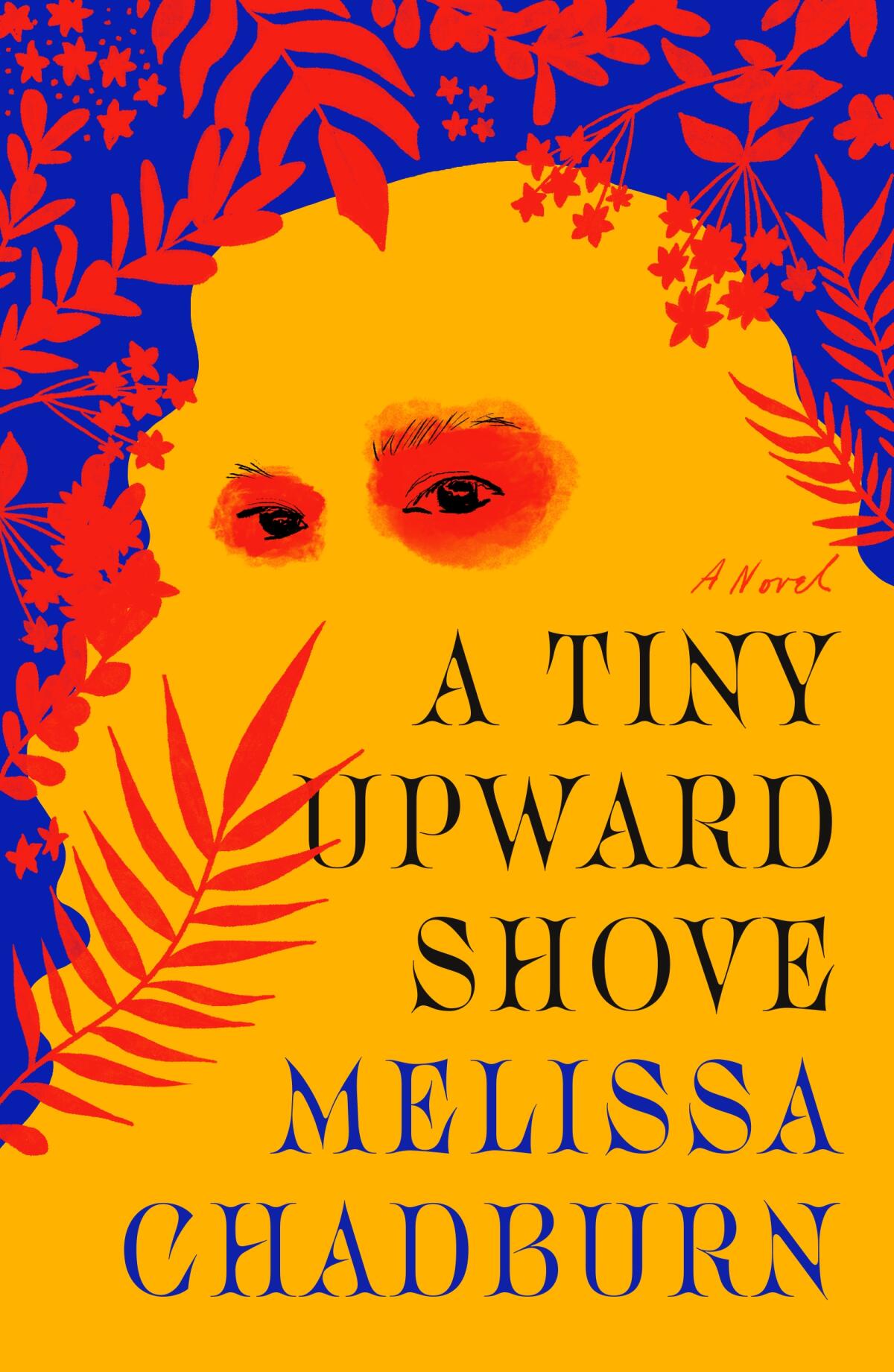

Review: A murdered L.A. woman gets her revenge in a shocking, redemptive debut novel

On the Shelf

A Tiny Upward Shove

By Melissa Chadburn

FSG: 352 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Many years ago, my husband worked as a military prosecutor on a large Army base. The stories he brought home every night ranged from silly mishaps (a sergeant who fell asleep on his car horn) to accounts so traumatic I asked him to stop sharing them. At the time, I was teaching at night and spending days home alone with our toddler daughter; there was no room in my psyche for tales of abuse, addiction and violence.

Melissa Chadburnâs brilliant and terrifyingly honest debut novel, âA Tiny Upward Shove,â has a moment of such similar horror that I was once again tempted to skip the whole story. Lucky me: privileged enough years ago to say âThatâs enoughâ to my husband in my cozy house with my healthy, happy child, privileged enough now to put down a book in which a toddler is locked in a closet until barely recognizable as human.

Chadburn has made herself a different kind of luck. A native Angeleno of Filipino heritage, she survived Californiaâs foster-care system to become an activist for women and children. Then she turned to fiction, displaying the talent and compassion (note I did not say âempathyâ) to give voice to every one of the intertwined characters in her debut novel. These include a real-life Canadian serial killer, Willie Pickton, whose 2007 conviction for the murders of six women led to the discovery of dozens of bodies at his pig farm on the outskirts of Vancouver.

The protagonist at the center of Chadburnâs fiction is Marina Salles â and also the creature who inhabits her soul after her gruesome death. Marina, a âBlackapinaâ (she never knew her Black father), is doted on by Lola (Tagalog for grandmother) until her mother, Mutya, decides theyâll strike out on their own, drifting through L.A. and its outskirts and shattering Marinaâs future.

She threw a welcome party for herself at the Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, a beautiful old building with black and white marble, Alice-in-Wonderland floors.

Hunger and neglect lead to worse â to the 13-year-old Marina being sadistically raped in a bathroom by a friend of her motherâs, to a foster-care facility known as the Pines and finally to her becoming, at 18, Picktonâs 49th and final victim.

We know the contours by the end of the first paragraph, which is when we meet Aswang, Chadburnâs variation on a mythical Filipino shapeshifter commonly depicted as a vampire or a warebeast. âI need to close my jaw around his neck. I need to sink my teeth into his skin,â Aswang says. âI need to taste that raunchy yellow man who killed Marina. ... This is not a hunger Marina ever felt. I am not Marina Salles anymore, no Blackapina foster girl. I am Aswang. And this is a hunger only we vengeful feel.â

Chadburnâs trickster-predator creature frames a heroâs journey â perhaps an odd thing to say about someone who is dead on Page 1. But the arc is clear: Both as a living person and as an aswang, Marina goes on a quest, acts decisively in crisis and is ultimately transformed. In this way, Chadburnâs Marina â or her spirit â inverts the hero archetype: not only a woman, but a victim of a form of violence most often visited on women.

In her authorâs note, Chadburn draws attention to the real crimes her fiction draws from: âWhile my novel does not tell any of their specific stories, I believe it all too accurately reflects many of them.â

The power of âA Tiny Upward Shoveâ rests in her insistence that even the murdered had agency in their lives, no matter how forgotten or lost to themselves and society.

Bethanne Patrickâs April picks include highly anticipated novels from Jennifer Egan, Emily St. John Mandel, Don Winslow and Douglas Stuart.

Perhaps itâs her drive to amplify every voice that leads Chadburn to a risky and not always successful choice. She covers not just multiple narrators and perspectives, but multiple ways of setting them up and setting them apart. Sometimes we watch Marina in third person and sometimes we hear from her directly, narrating her short roller-coaster life. Her Lola also addresses Marina from the grave. More than halfway through, a long third-person section introduces a new character, Sabina. She becomes essential to Marinaâs story, but the narrative pastiche can be confusing, especially in close proximity to traumatic episodes.

Donât let the confusion â or the trauma â stop you short. Pick the novel back up again, as I did. There are payoffs and compensations, even in the most cursed lives. Marinaâs briefly happy time at the Pines with her girlfriend Alex may be the sweetest heroâs reward since Dorothy won the burned broomstick in âThe Wizard of Oz.â Their bond gives Marina the drive to fulfill a mission â a promise to Alex. She has just enough cash for a bus ticket to Vancouver and just enough strength from her grandmother and deeply imperfect mother to get there.

At the end of a heroâs journey, the protagonist is supposed to return with some kind of trophy: an elixir, a token, some symbol of redemption. Chadburn places Marinaâs death up front, but she also gives us her redemption: Aswang. This is the fantastical force that not only avenges Marinaâs murder but saves other women.

Chadburn has written a stunning debut novel about the hardest things, drawing on style, study and tough experience to make it impossible for us to look away. However much luck hovers over our lives, we are lucky to have her stories.

The author of âThe Handmaidâs Taleâ and a new essay collection explains the âwoman problemâ embedded within L. Frank Baumâs âWonderful Wizard of Oz.â

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.