Imani Perry on how the racial sins of the South belong to us all

- Share via

On the Shelf

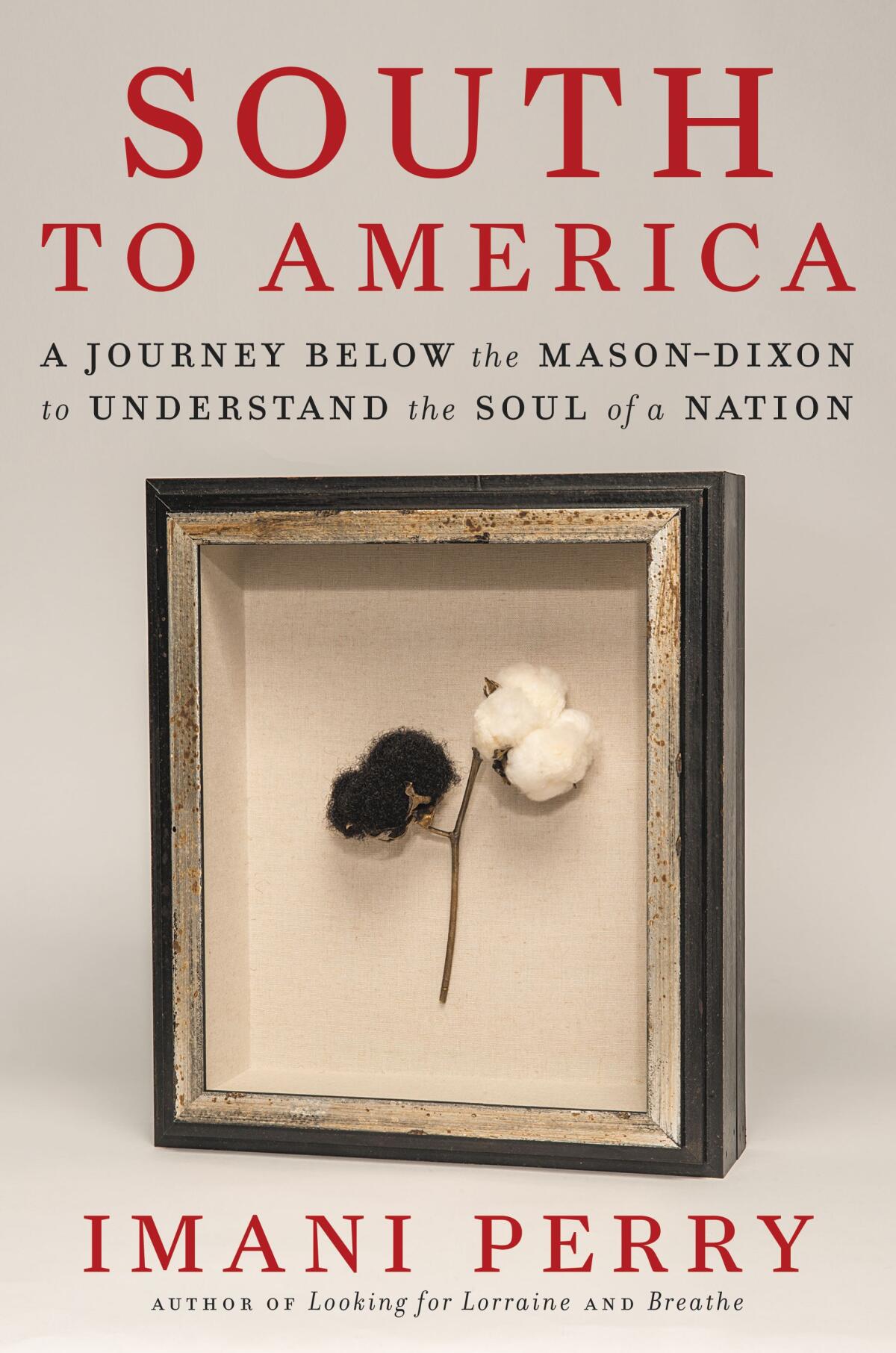

South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation

By Imani Perry

Ecco: 432 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Imani Perry’s new book, “South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation,” is a cultural, historical, social, intellectual, political and personal tour.

A native of Alabama who was raised in New England, Perry considers the South home despite living in Philadelphia. Her condition of quasi-exile allows her to consider the South from within and without and to explore its relationship to the country as a whole. “ ‘American’ means something, even though there’s an intense set of divisions and inequalities that are part of its story,” Perry told me. “The South becomes an encapsulated version of the core of the complication of what we are.”

The author takes us along on taxi rides to speaking engagements, to the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, inside a tourist cave and much more, with the question of race and racism always at her back. She tells rich stories of place while ignoring the borders dividing disciplines and genres, weaving personal experiences with deep history, economics and cultural critique.

Perry is the Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies at Princeton University and author of “Breathe: A Letter to My Sons” as well as an award-winning biography of playwright Lorraine Hansberry, “Looking for Lorraine.” We spoke this month via Zoom; our conversation has been edited.

Even as a backlash brews over teaching America’s racist history, ‘Forget the Alamo’ and ‘How the Word Is Passed’ tell of the full, inglorious past,

You write about “a collage of historical meaning” in terms of thinking about where we come from. For you, was the book also such a collage?

Oh, yes. I mean, both personally and in the sense of where I’m situated socially and historically. To be born — and this is relevant now because we’re talking about the Voting Rights Act — to be born seven years after the Voting Rights Act, only seven years into when my people, literally, my family, had access to suffrage rights. And only nine years after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, in some ways at the crossroads of history, [which] on one level is treated as a heroic, triumphant history, right? The Birmingham struggle was extraordinary, but on the other hand is where we still are. We’re still at this crossroads moment where the question of suffrage, the question of racial violence, is still so present. The South is the primary grounds for thinking through what this all means in terms of who we are.

I’ve never felt anything but Southern, even though I’ve lived most of my life outside the South. This is an anchor for me. The personal part is piecing together why this region is where I feel like I make sense as a human being, even though I don’t live there. That’s tracing through the idiosyncrasies of my own story — and also the idiosyncrasies and the submerged parts of the American story.

You write more than once about how “the South is supposed to bear the brunt of the shame, and the nation’s sins are dispensed upon it.” I think many L.A. Times readers in California might think racism isn’t our problem. Like, it’s easy to dismiss it as “other.”

Wow. [laughs] I mean, there are many wonderful things about L.A., but having had family that moved from Alabama to L.A., that would be a huge mischaracterization. Everyone has gone back South. The promise of L.A. proved not to actually be as promising. I’ll say, having left Alabama young and spent most of my time coming of age in Massachusetts, one of the things that’s interesting for me is I experienced many more acts of racial aggression in Boston than in Alabama. Slurs, physical aggression of a sort I’d never experienced.

I think this is how people are socialized to think about racism, right? We are trained to think of racism as a Southern problem, as opposed to thinking the ways of the South shaped how we do race everywhere. The fact that the nation began there, built its prosperity off Southern land and unfree labor, and also the genocidal relationship to Indigenous people that becomes a way of doing things. So when we talk about gentrification, we need to think about that as rooted in the very beginning: Just move people out. When we talk about extreme poverty, children in cages, all those things come from this history; we have learned these habits. So to tell the story of the South as the story of the nation helps us all become more honest about what this nation is. That’s the precursor to really deep transformation.

Nikole Hannah-Jones talks about power, privilege and ‘The 1619 Project’ in advance of her L.A. Times Book Club visit.

The Great Migration is often portrayed as a heroic narrative of Black people coming into their own by moving to places where there’s more opportunity than in the South. But you write about Birmingham that “staying alive on the grounds of your ancestors’ murder and abuse is no small matter.” Could you talk about that?

The Great Migration is, as Isabel Wilkerson writes, perhaps the most significant internal migration. But it’s also the case that it was never the majority of African Americans who left. To this day, the majority of African Americans live in the South; it’s always been over 50%. And white Southerners migrated too, in even higher rates. So the migration is as much about work and the boll weevil as it is about this notion of opportunity. I think that’s really important because while for many people it was about seeking out a better fortune, for others it was that there’s no more agricultural labor. It was rural people who disproportionately migrated; they migrated to Northern cities, but they also migrated to Southern cities. I always say my family’s not a Great Migration family, but we are in a sense that we moved to Birmingham.

I ask this in the book: We have an answer to why people left, but not why did people stay. And it’s a personal question because my family is still overwhelmingly based in the Deep South. I think it has to do with a sense of home and connectedness to history and community. What did it mean to stay and fight? Fight in the sense of the movement, but also just to make a life, to get educated, to build schools. Homeownership rates are much higher for Black people in the South than other regions. That’s a really important part of the story too.

And having homes enables building intergenerational wealth, which white people still have way too much of the share of.

I love that you made that point because there’s a great book that lays this out in terms of economic history, “Whitewashing Race.” The way that homes are valued was a matter of policy. The home that my family has was bought in the 1960s, but the appreciation of the home is not as great were it in the white neighborhood. That’s not because the home isn’t taken care of — all the homes on the block are taken care of. There just was a set of decisions made by the federal government that homes in Black neighborhoods were worth less. That’s a national policy, not a Southern policy. But also things that seem like they just happened, were made. They were built.

Taylor Harris discusses ‘This Boy We Made,’ her memoir on seeking answers about her son, the anxieties of Black parenting and her evolving faith

Tell me a little bit about how you became the kind of scholar you are.

I grew up in an intellectually nurturing environment and learned early the passions of the life of the mind. I was never a conventional scholar but something closer to conventional than what I am now. I realized that it was as important to me to try to write to people’s heart as their mind. I didn’t want to live in a place submitting to the Cartesian anxiety that the mind and the body are disconnected. As scholars, we often play at pretending we’re impartial and distant, but everything you try to study is a passion project.

That was an organic unfolding as I moved through the career and as I answered the thing that had always moved me, which was to try to write meaningfully. And as I thought about why music and literature were for me the inspirations. I was once interviewed for a fellowship and they asked me, which writer are you most shaped by? And I said, Thelonious Monk. They said, can you name a real writer? [laughs] Writing music is writing. I meant: He’s elliptical and experimental and returns to themes. To do this work that brings in law and history and storytelling and the creative imagination and art is to just be honest to how I’m moved and shaped.

Kellogg is a former Books editor of The Times. She can be found online at @paperhaus.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.