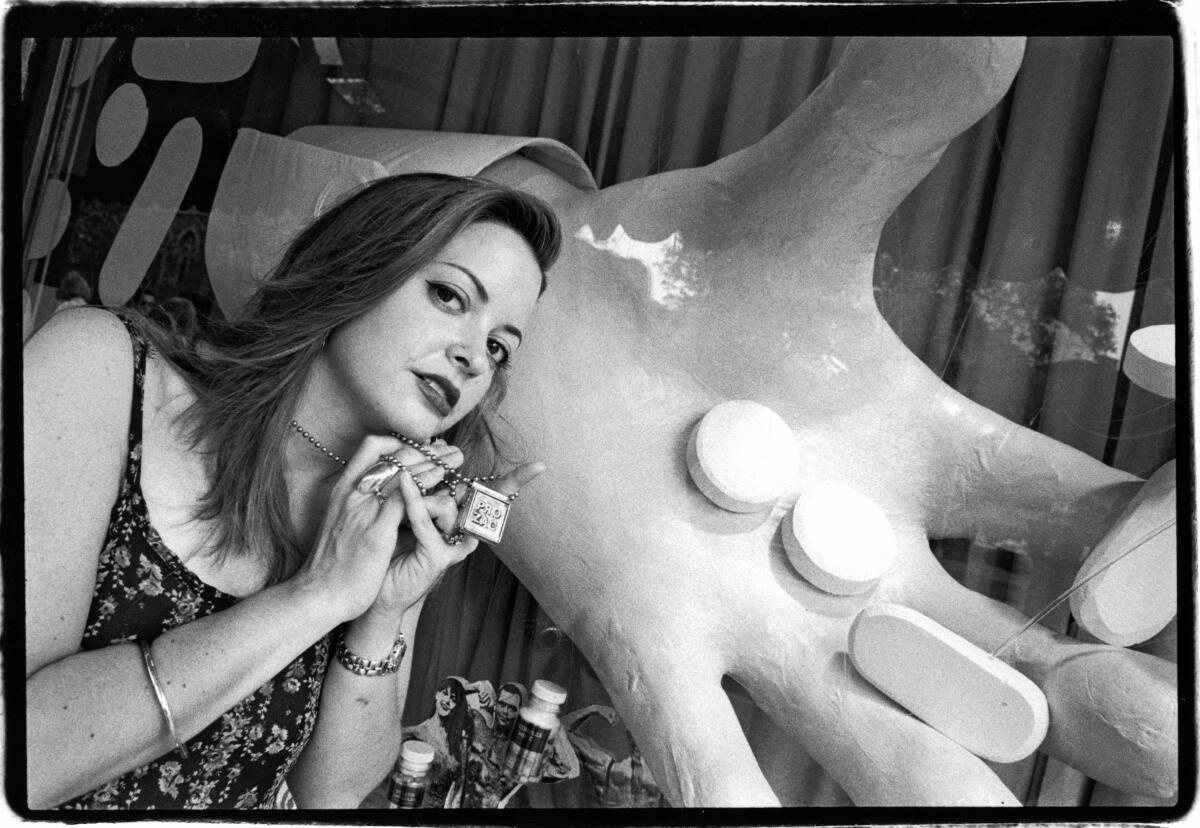

Appreciation: ‘Prozac Nation’ author Elizabeth Wurtzel chronicled the world’s woes and her own with gusto

Really, the only person who should tell Elizabeth Wurtzel’s story is Elizabeth herself, in her singularly unminced words, because her story is too kaleidoscopic for any kind of newspaper obituary, even one that compares her to Amy Winehouse or Baudelaire.

Her moods, her moral commitments, her conceptions of men and romance and vanity and Israel, even who her parents were — all of it was always changing. The story ended this week, when she died at 52 after battling breast cancer. It started with the first line of her first book: Something is really wrong.

With precision — also recklessness — Elizabeth chronicled wrongness, the world’s wrongness, her personal wrongness, and the beauty of all wrong things in “Prozac Nation,” about her depression; “Bitch,” about her temperament; and “More, Now, Again,” about her drug addiction. She also published hundreds of articles on topics ranging from intellectual-property law to hair loss from cancer treatments.

“I love to argue,” she wrote in 2018. “I am in it for the headache.”

Elizabeth found herself extremely difficult. I did not. As I look over emails from her, I find she never failed to check in after big events, to offer congratulations or condolences. Other times she sent photos of my kids, the odd good word, a fantastic anecdote. It’s hard to convey, without screenshots of email and texts, how generous she’s been for the last two decades. Though her books were made of sublime laments and self-savagery, she was wide-smiling and bright-eyed in person. I’m thinking of that grin right now, her passion for her dogs, and the neo-coral lipstick, and how she considered cancer her “final con.”

But if she gave her friends love, she did seem to give herself a headache. She was her own best perceiver, so I have to trust her on that. In her work she unflaggingly beheld her own existence, and existence itself, in suspended animation; she was forever on high alert to how existence felt on her neurons, her fingertips, her face, her legs, her bloodstream.

Elizabeth Wurtzel, who wrote influential memoirs documenting her struggles with addiction and depression, died Tuesday at age 52.

“A rainbow does not see it has color,” Elizabeth wrote, in 2017. But she somehow could see the full spectrum of her own refracted light.

I met Elizabeth first in the mid-1990s, not long after “Prozac Nation” came out, when she was famous for self-harm and exhibitionism, but also for writing with cracked brio about pop music for the New Yorker. Socially, she was ... maybe the phrase is “a piece of work.” For years I studied her from a safe distance, starstruck, until I came to know her more intimately through my ex-husband, who was her oldest friend.

Our friendship survived the divorce. In middle age, conspiring with her in the corner of a book party or a bar mitzvah was delirious fun — better than the cocaine we both regretted doing when we were young. Often we talked about sobriety.

What came to mind on Tuesday, the minute I heard she’d died, were a few impromptu comments she’d made about watching the twin towers fall on 9/11.

“I had not the slightest emotional reaction,” she told a journalist in 2002. “I thought: ‘This is a really strange art project.’ It was a most amazing sight in terms of sheer elegance. It fell like water. It just slid, like a turtleneck going over someone’s head.”

Like everything else about Elizabeth, the wild and whirling observations were dutifully framed as “controversial.” At Miramax, the movie production company, people were especially incensed. To “err on the side of sensitivity” — good old sensitive Harvey Weinstein, who started and ran Miramax — the company shelved the movie of “Prozac Nation.” What a jerk move. With her words, Elizabeth had in fact expressed the paralysis — and trauma — she’d experienced watching the World Trade Center being emulsified from the building next door. Two years later, her dog Augusta was trained as a PTSD service dog, and went with her everywhere; when Augusta died, her beautiful dog Alistair had the same training. Elizabeth with her dogs was a whole Elizabeth.

Did I say Elizabeth went, later in life, to Yale Law School and worked with David Boies? That she presumed when she turned 41 that she’d never marry — and then did? That she discovered extremely recently that her father was not the person she’d grown up believing he was? That not a single person who met Elizabeth in later years didn’t marvel at how open-hearted and heart-opening she was?

“More, Now, Again” opens with an epigraph from St. Augustine’s “Confessions.” “Too late came I to love you, O your Beauty both so ancient and so fresh, Yet too late came I to love you. And behold you were within me and I, out of myself, where I made search for you.”

“Life is just a shock to the system,” she wrote in 2018. She was available for the shocks. She let herself feel the shocks — and one day the shocks were love.

Elizabeth will be credited with inventing the confessional memoir, but as a learned student of Augustine, she’d brush that off. Like Augustine she worried she’d be too late for love. But for Elizabeth, and in Elizabeth, it came just in time.

Virginia Heffernan is a regular contributor to the Times Opinion section.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.