- Share via

Fifty-five years ago, Mexico’s authoritarian government killed student demonstrators during a peaceful rally in Mexico City. It would later become known as the Tlatelolco massacre.

Mexico was the center of international attention in 1968 as it was set to host the Summer Olympics, an opportunity to showcase the nation’s economic growth and stability.

In the months leading up to the international sporting event, students rallied against the Mexican government, which had been under the rule of one political party — the Institutional Revolutionary Party — since 1929. Activists fought against the government’s economic and political suppression, particularly against labor unions.

On Oct. 2, 10 days before the start of the Olympics, an estimated 10,000 students peacefully assembled and demonstrated at the Plaza de La Tres Culturas. They chanted, “¡No queremos olimpiadas, queremos revolución!” (“We don’t want the Olympics, we want revolution!”)

The United Farm Workers union is endorsing President Biden for reelection, saying it would be a win for labor rights and the ‘daily lives of farmworkers across America.’

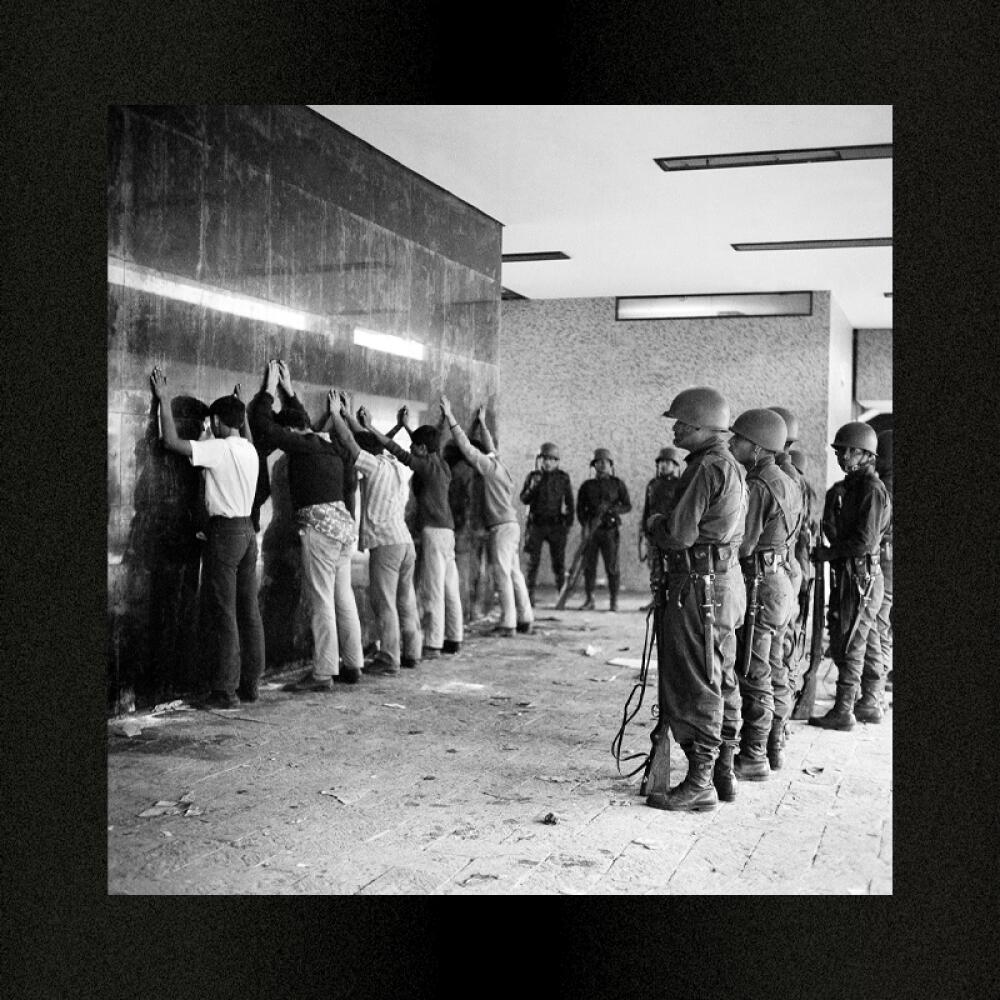

Government troops marched into the plaza and opened fire on the unarmed civilians, later claiming that demonstrators acted violently.

The exact number of deaths is uncertain. Estimates range from 44 to more than 400 deaths. In addition to the killings, more than 1,000 people were beaten and arrested. The massacre was initially portrayed as a violent student uprising, though countless interviews with survivors indicate that the demonstration was peaceful. Military reports indicate that at least 360 government snipers were positioned in buildings surrounding demonstrators.

In Jessie Fuentes’ hometown of Eagle Pass, he sees concertina wire and a floating barrier outfitted with serrated blades on the river where he grew up.

In 2002, then-President Vicente Fox ordered a special prosecutor to investigate the mass shooting and other incidents pertaining to Mexico’s “dirty war” against left-wing activists.

The investigation resulted in genocide charges against former President Luis Echeverria, who was interior minister and in charge of national security at the time under the administration of President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz.

Echeverria denied any wrongdoing.

Efforts to prosecute Echeverria failed in 2007. The special prosecutor’s office was shuttered that same year, leaving many unanswered questions.

In 2008, Times reporters Tracy Wilkinson and Deborah Bonello wrote about the Tlatelolco massacres and its lasting impact on its 40th anniversary, noting that the attack has become a symbol of “Mexico’s entrenched culture of impunity, in which rampant killings and kidnappings are rarely resolved.”

In 2018, a week before the 50th anniversary, a Mexican government agency finally acknowledged the mass killing as “a state crime.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.