DC Comics is about to release its new movie, âBlue Beetle,â the latest superhero-driven attempt from Hollywood to provide representation of Latinidad with all of its beauty, comedy and complexity (including our favorite heroĂnas, the nanas or abuelitas).

Our culture has always embraced the presence of powerful and mysterious beings protecting us. Blue Beetle might just be the latest link in that long chain, which started even before the current geopolitical map of our continent was traced.

Of gods and magic

Tradition in the pre-Columbian, pre-Euro-colonized societies and civilizations was filled with fantastic humans gifted with amazing, magical powers that sometimes turned them into gods. Among them is the Mesoamerican QuetzalcĂłatl, at times a powerful god, at times a mythical leader.

More than four decades ago, groups of Black and Latino journalists embarked on an endeavor to tell stories about their communities that the Los Angeles Times was failing to showcase.

The figure is still debated and analyzed by experts. The Toltecs had a ruler called Ce Acatl Topiltzin QuetzalcĂłatl, a beloved, powerful and monk-like wise man who allegedly led communities into progress, until he mysteriously departed after getting drunk and failing to lead by example.

But for the Mexica (or Aztecs), there is the god QuetzalcĂĄtl, most likely created as an evolution of the historical figure. The âQuetzal-Feathered Snakeâ is the lord of the earth and skies, creator and protector of the people â and a man turned into a god.

Later, Europeans would bring their stories of gods, demigods, and heroes. The Greek and Roman pantheon, along with the Christian narrative, became part of mestizaje and mixed with the tales of the pueblos originarios. Many Catholic missionaries adapted the stories of Mary, Jesus and the apostles to the nature-driven polytheistic imaginary of the Americas for successful indoctrination.

A contemporary case to illustrate this mythical mestizaje could be the merman Nemor, an old comic book character that recently resurfaced â no pun intended â in the Marvel multiverse with a âLatinizedâ identity. While the original American character was inspired by Greek mythology and portrayed him as ruler of Atlantis, the new version sets him as king of Tlalocan, the paradise of the Mexica god of rain, TlĂĄloc.

Bandidos y forajidos

Inhabitants of the European colonies in the Americas also created their heroes in literature and anecdotes, reflecting their struggles to build their own identity and their fight to become independent state-nations.

One of the most interesting examples comes from two Robin Hood-esque outlaw bandidos. And they both may share the same destiny in comic books and movies through different characters.

The first one is William Lamport, later Castilianized as GuillĂŠn de Lampart. The Irish pirate and adventurer allegedly mingled with Spanish royalty in the early 1600s until he was exiled to New Spain (later Mexico) after, well, flirting with the wrong â married â woman. De Rampart apparently liked it there and tried to start a revolution against the colonizers, but the Spanish Inquisition captured him and burned him at the stake, accused of sedition and â of eating peyote. He is still revered as one of the first martyrs for Mexican emancipation.

The co-host of âDrag Race Mexicoâ sat down with columnist Suzy Exposito to discuss her illustrious television career, her Chicana pride and the freedom of being nonbinary.

The other one came about 200 years later. JoaquĂn Murrieta was a Californio who supposedly fought against American colonizers arriving during the Gold Rush, after the U.S. invasion of Mexico. Legend says Murrieta lost his family at the hands of the new settlers and, in vengeance, would continuously rob them to spread the riches among the segregated and impoverished Mexicans, until he was killed.

It is very likely that, in the early 20th century, a journalist and history buff named Johnston McCulley would hear about both, or at least one, of those characters, which would inspire him to write a pulp novel about a hero with a double identity fighting against the corrupt government of Mexican Alta California. His name? El Zorro.

The adventure story would soon become suitable for the young Hollywood industry, and its anti-Mexican sentiment was well received by supporters of the Monroe Doctrine. The masked, caped Hollywood hero was born. And a fan named Bob Kane would find some inspiration in him to create, along with Bill Finger, another famous avenger with an identity crisis: the Batman.

Globalizing our heroism

The 20th century and its mass media brought more heroes. And in a world seduced by Americana, striving to become globalized, the new concepts of our heroes aimed to be more universal, yet still very local.

Mexican radio and magazine publishers would create characters such as KalimĂĄn, a descendant of the Indian goddess Kali trained in the Himalayas, who uses mental powers and Buddhist-inspired techniques to fight evil.

And for many, the first masked superhero in Latin America, or at least Mexico, was a result not of literature, but of real-life wrestling. Hiding his identity in lucha libre fights in the 1950s and 1960s with a silver mask, Rodolfo GuzmĂĄn became an icon under the name that would turn him into a legend: El Santo. His popularity would take him to the movies, where he would portray a lucha libre champion always ready to fight against supernatural creatures or Cold Era enemies using his strength, intelligence and high-tech gear.

And of course, if you are Latinx, we know that comedy and heroism can come together wearing a red grasshopper costume. El ChapulĂn Colorado was the silly yet noble superhero created by Roberto GĂłmez BolaĂąos âChespiritoâ for his worldwide TV show. An urban legend says the character inspired âThe Simpsonsâ writers in creating the infamous Latino-ish Bumblebee Man.

Searching for new idols

The cultural industries of the 21st century have âdiscoveredâ (wow! â Iâm being sarcastic) the buying power of the US Latino and Latin American markets. Latinidad is more present than ever.

In the not-so-distant past, Latinos were basically non-existent in Hollywood or reduced to secondary characters (the noble native or the naive buffoon) or evil nemeses (thugs and liars). But now, more and more Latinos are getting main roles and better portrayals of their culture, even in the superhero trend.

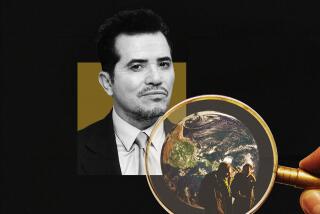

Like other movie superheroes, Blue Beetle is a character brought from a comic. But perhaps the film is also trying to reclaim our tradition with so many Latinos as main characters, actors and talents behind the scenes, including Boricua director Ăngel Manuel Soto, Mexican writer Gareth Dunnet-Alcocer and Mexican American actor George LĂłpez.

In the past, real and imaginary heroes gave our ancestors hope and inspiration. With the world more divided than ever, who would not give a chance to a superhero who might not save us in real life, but at least inspire us to fight for whatâs righteous and bring a smile to our faces?

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.