- Share via

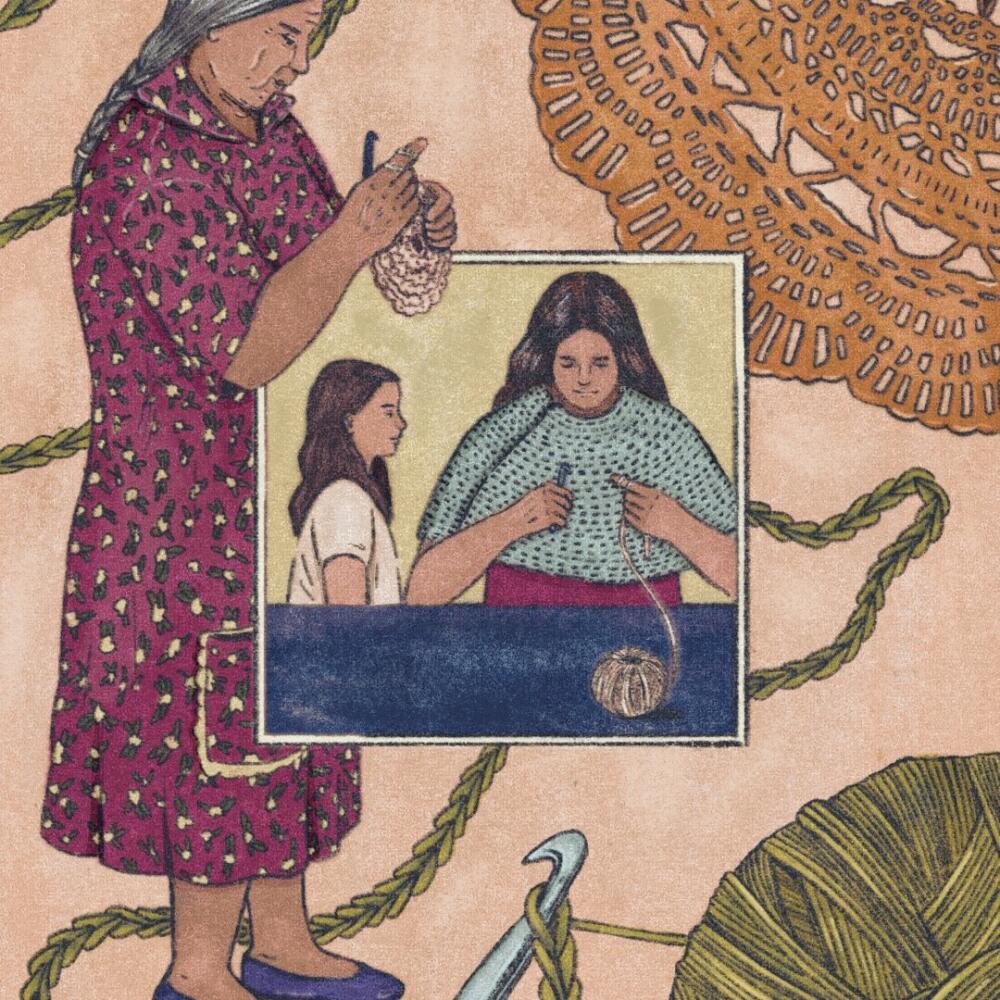

From childhood, crochet has connected me to the important women in my life. In the fourth grade, Juliette was one of my first best friends, and the first person to teach me how to crochet. We spent our free time making doilies and flowers, enamored by the fun of making beautiful things. I didn’t know it yet, but she wasn’t just including me in the lore of yarn — she was also teaching me about friendship and the sacred act of creation.

Derived from the French word meaning “hook,” crochet differs from knitting because it uses one hook instead of two needles. It’s also more forgiving than knitting, as it’s easier to undo, restart and repair since the stitches can stand alone, and are not dependent on the ones before. I love to crochet for this grace and for its certainty. Whether it takes me a few hours or a month, there’s a tangible finish line with a completed project in hand, and everything about it feels exciting and reachable and possible.

What I didn’t know is that crochet actually has a pivotal role in the history of Mexican craftsmanship. While crocheting is of European origin, there is a Mexican craft known as “randa” that is similar to crochet that dates to pre-colonial times. Artisans from Indigenous groups would use maguey cacti to create a fine thread, which would then be weaved with crochet-like techniques. Though not well known, the craft is still practiced today in many Mexican states.

For over 180,000 Ecuadoreans in New York City, ecuavoley, a sport from their homeland, brings together identity, community and an opportunity for mutual aid.

Of course, the only reason it exists at all is because of colonization, which saw the enslavement and near eradication of Indigenous peoples and their practices. But to me, it’s not just a case of “randa good” and “crochet bad.” While I would love to learn randa, and maybe even traditional Otomi embroidery, crochet has taken on a life of its own in Mexico and in families like mine who learn the techniques and pass them on to their descendants.

For many years after my fourth-grade lessons, I didn’t crochet. But everything changed when I was 20 and COVID-19 became a painful part of our lives. My college classes went completely remote, and because my dad had to travel for work and could have exposed us every time he came home, my mom and I moved in with my tía and abuela. Despite the closeness we felt living together during that time, we were undeniably isolated from the outside world and experiencing so much free time that it was more stifling than comfortable.

To pass the time, my mom and I decided to pick up crocheting again, which turned out to be a homecoming for both of us. We had both been taught by other people, me by Juliette and her by her grandmother as a child.

Daniel Flores embraces identity, music and culture on TikTok with help from his trumpet and the city of Chicago.

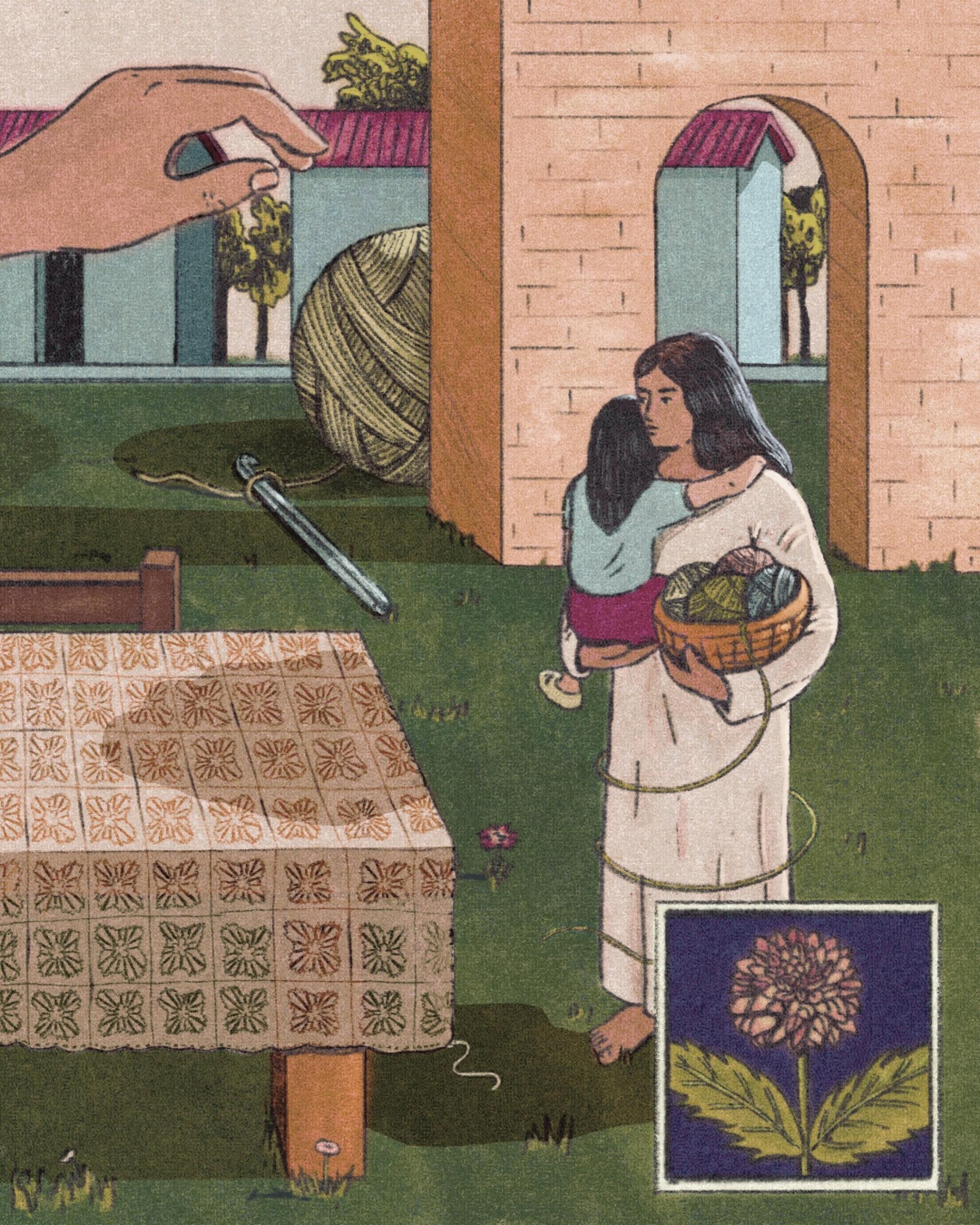

In returning to crochet, we were relearning and discovering techniques together in a reciprocal way. While she taught me how to read patterns and how to use more complex stitching, I showed her how to imagine possibilities for bigger and more fun projects outside of traditional crocheting. Suddenly, we were no longer satisfied with just making squares for a blanket. Our projects turned to beautiful summer tops, sweaters, jewelry and dolls. But even more than improving our crocheting skills, the time that we spent together led to incredible and thought-provoking conversations, reflections and rewatching our favorite movies as we worked.

But up until recently, I’ll admit that crochet has sometimes felt like a betrayal of my identity. As the child of a Mexican family, I’m all too familiar with the costs of colonization and loss of culture. Enjoying something as European as crochet, even when it’s harmless and fun, can feel strange and wrong, or at least it did for me. Especially when the crochet community online and in real life, which is heavily saturated by white creators and artists, asks questions like “Is this just a white girl hobby?” Not that I was surprised.

I love to crochet, but I love it even more now knowing its connection to a culture that, in so many ways, has made me who I am. With every stitch, every loop and every turn of the hook, I’m carrying on the legacy of my great-grandmother, my mom and the cultural history of Mexico. Take Diego Armando Juarez Viveros, one of the most prominent male crocheters from Mexico who crochets large, wearable works of art to connect with and honor his Indigenous heritage. Or Yolanda Soto-Lopez, a Mexican American woman who has amassed millions of online fans for her crocheting tutorials on YouTube.

Learning Spanish wasn’t part of a quest for identity. I was proud of this fact; that I was pursuing fluency on my own terms and not for cultural credibility.

Last year, 200 artisans in Jalisco made headlines for crocheting the world’s largest “woven sky” across the town of Etzatlán in order to pay homage to their Indigenous roots and religious beliefs, as well as bring an entire community together.

I could argue that crochet is actually the most Mexican thing I could ever do.

Sofía Aguilar is a Chicana writer based in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the L.A. Times, Refinery29 Somos, and New Orleans Review, among other publications. @sofiaxaguilar

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.