Newsom’s top education advisor bares his mental health struggle: ‘You’re not alone’

- Share via

The boy hated himself.

Six months into his first year in high school, he dropped out. For more than a year, he isolated himself in his Huntington Beach bedroom where he became addicted to video games and anonymously vented his anger online with racist and misogynistic screeds, haunted by suicidal thoughts and fantasies about hurting others. His health deteriorated as he binged on pepperoni pizza, grew obese and developed terrible rashes.

Then Ben Chida ventured out of his room.

Today, Chida, 38, is Gov. Gavin Newsom’s chief deputy Cabinet secretary, a key member of the team building an ambitious plan to reshape public education through a $50-billion continuum of services to create a healthy foundation for children and a path to meaningful jobs at the end.

Chida was the chief architect of five-year compacts with the University of California and California State University, pledging financial stability in exchange for gains in graduation rates, access and affordability. He guided a statewide data system, set to debut this year, to follow students through the educational pipeline into careers to assess what works and doesn’t.

He is driving Newsom’s Master Plan for Career Education, set for release this fall, that would help high school students explore potential careers, build job skills while earning academic certification and access greater state financial and counseling support.

Yet Chida still struggles with his mental health. He has thought about suicide every day since he was 14 — including now — although he doesn’t take steps to act on it. On some days, he lies on his office floor, seething at his inadequacies and then projecting his bitterness toward colleagues with impatience and verbal lashings. He is known to be condescending and disrespectful at times.

Chida recalled that he once unloaded a profanity-filled tirade at an educational nonprofit’s board members who had invited him to dinner a few years ago — “a really lame thing for me to do ... that wasn’t my best self.” Michele Siqueiros, president of the Campaign for College Opportunity, said the outburst was “inappropriate and challenging, but it didn’t stop us from moving on and working together,” including work supporting students by largely eliminating remedial classes in community colleges and streamlining the transfer process to universities.

Another person who experienced Chida’s anger was startled by the behavior but found candor in his heated words and a willingness to move beyond disagreements to look for solutions.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

“I want to be a good, kind, authentic person to everybody,” Chida said. “But I get stressed and overanxious. And the way I manifest that is I lecture somebody or I get in a fight. I’m not proud of that.”

But Chida’s dark past has become his road map to diagnose problems in the traditional education system — and advocate for changes so fewer young people fall through the cracks like he did. He wants to do so with raw, honest conversations, not polite policy discussions.

Chida said he is sharing his life experiences to give a message to young people who are struggling with self-hate, social isolation, anxiety and school absenteeism. And he wants to reassure the adults in their lives as well.

“You’re not alone. It’s not your fault,” he said. “It’s on us that we have not done a good enough job supporting you.”

Newsom, in an interview, said Chida’s willingness to share his personal trauma has brought greater meaning to their work. He said he was always impressed with Chida’s “next-level intellect” and powerful analytical skills he likened to a human ChatGPT.

When Chida began sharing his personal journey, Newsom said, it opened up others on his staff to share their own insecurities, including his own. Newsom said he too struggled with school and self-esteem due to dyslexia.

“The more he talked about it, the more everyone else talked about it. And all of a sudden you realize … we’re all a work in progress,” Newsom said. “It’s a real crisis of loneliness, of isolation, feeling inadequate, not good enough. And it’s just of epidemic proportions, with social media exploiting that anxiety in profound ways.”

::

Chida was born scrappy — heso magari, literally translated from Japanese as a crooked belly button, a phrase that connotes a contrarian and obstinate nature, his mother said in an interview.

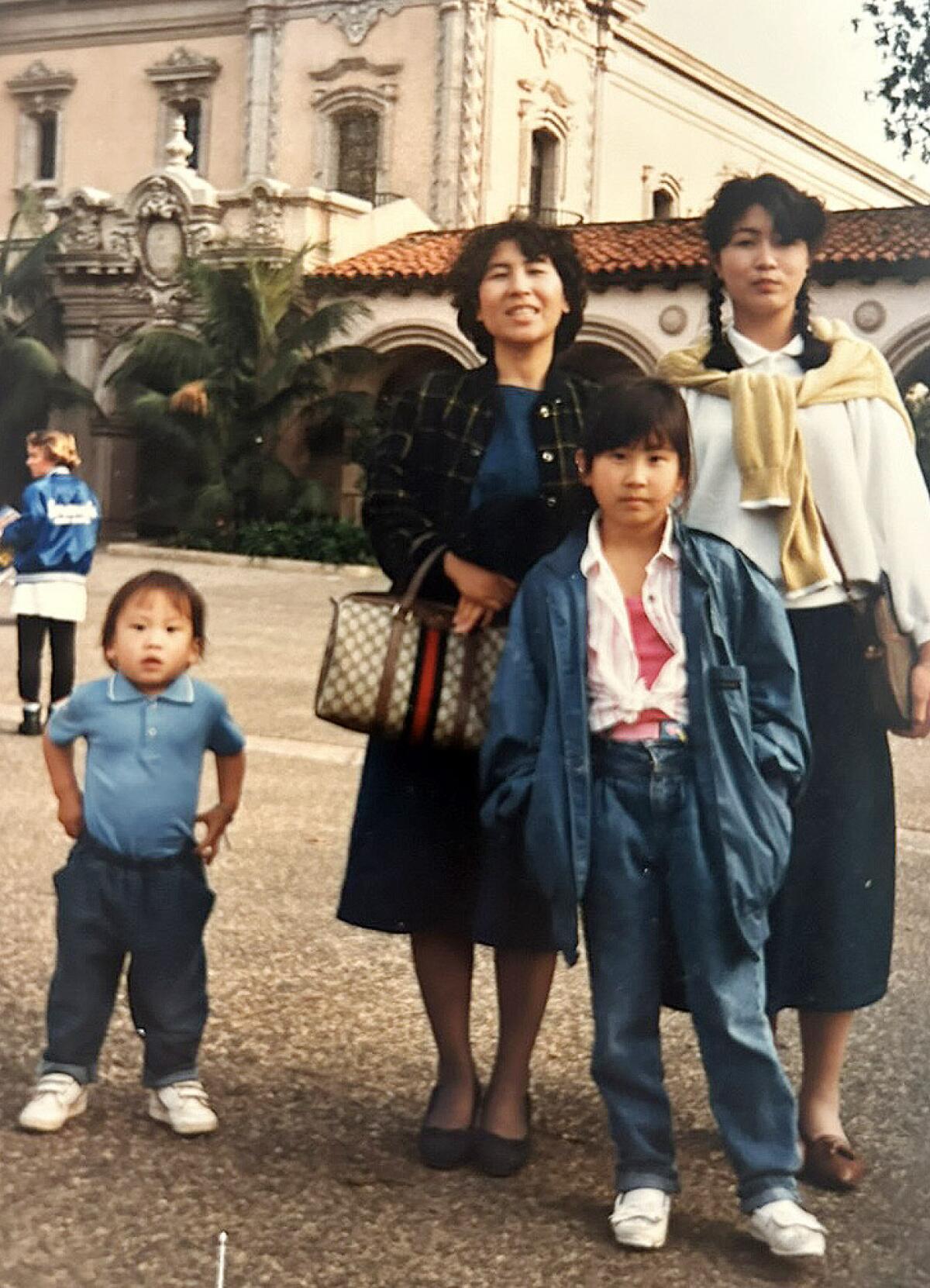

His parents were immigrants from a remote area of northern Japan — his father, Tetsuro, was a roofer, his mother, Teiko, a home health aide — who were under constant financial duress. The family of five lived near the poverty line, with a $30,000 household income in 2005, and struggled with a business bankruptcy and home foreclosure. The enormous stress led his father to the bottle and physical altercations. Chida, who was born in Fallbrook, Calif., as the youngest of three children, said he bore the brunt of the abuse.

He tested boundaries and, when physically disciplined by his father for his rebelliousness, he fought back. “My husband was very strict, but Ben was the most difficult of my three children,” Teiko Chida said, adding that he raised hell even at preschool, kicking his teacher and refusing snacks.

As a child, he was a leader — organizing neighborhood friends to build a clubhouse using materials from his father’s business. But, Chida said, he was also a bully who would dominate and control others in what he now sees as a misguided conception of masculinity.

“I remember distinctly wanting to be strong and looked down on those who weren’t,” he said.

Even at a young age, he knew what he wanted: to escape the financial stress that damaged his family. He kept a photo of tech billionaire Bill Gates’ mansion in his wallet and hustled to make money by selling golf balls he retrieved from a nearby course and pagers and beepers at marked-up prices.

Academics came easy, landing him in gifted and accelerated classes. But as he entered eighth grade, family financial tensions mounted. His older siblings were off on their own, leaving Chida in a traumatic home environment. He began to ditch middle school. His grades fell. He entered Edison High School in Huntington Beach on unstable footing and dropped out during his first year in 2000.

The collapse culminated “years and years of anger,” Chida said, leading him to project hatred online — even fantasizing about committing violence.

“You’re angry and you’re resentful and you feel lost, and you feel unseen and you feel like people hurt you,” Chida said. “And the internet is enabling you to think these sorts of ugly thoughts.”

It’s why the pandemic school closures that brought on a mental health crisis among many teenagers hit Chida in a deeply personal way — dredging up the pain of his teenage self.

His mother said the school called a few times, but her son would say he didn’t feel well. Like many immigrants, Chida’s parents were unfamiliar with U.S. educational laws and procedures. They asked him why he didn’t want to go to school, his mother said, but he would never explain and they did not probe, reflecting a common Japanese cultural reticence to openly discuss sensitive issues.

Once, Chida’s father came home from work midday and found his son’s bedroom door locked. He kicked it down, looked at Chida and left without a word. They still have never spoken about that day and the door was never fixed. Teiko Chida said her husband broke the bedroom door lock because they both feared their son would take his own life while holed up inside. As he hit more than 300 pounds and developed skin rashes around his neck, stomach and legs, she cried every day.

She began reading up on a phenomenon in Japan of severe social withdrawal called hikikomori, in which individuals may isolate themselves in their parents’ homes for six months or longer. She followed the advice not to push her child and instead support him with love. But the parents insisted Chida leave his room once a day for dinner with them, becoming closer.

Finally, in late 2001, Chida told his mother he wanted to return to school.

He’s still not sure why.

He was getting tired of playing video games more than 14 hours a day. He was becoming intrigued by the online political debates over 9/11 and the Iraq war. He had started watching “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” and USS Enterprise Capt. Jean-Luc Picard’s leadership and empathetic strength put him in a more hopeful frame of mind. Maybe all of that played a role, he said.

He went to Coast High, a loosely structured alternative school in Huntington Beach. That is where he met the man who would change his life.

Gerald McIntyre, tall and fit, was a former Marine and Vietnam War veteran who taught P.E. and history. When the 15-year-old Chida mouthed off against the war, McIntyre told him he disagreed and challenged him to write a paper to change his mind. Chida dived in, producing a 20-page paper about the lack of evidence for weapons of mass destruction.

McIntyre had reignited Chida’s desire for connection. He presented a strong and healthy model of masculinity. McIntyre was the first to suggest Chida enroll in community college, seeing how bored the gifted student was with homework packets. But the first class Chida took — on leadership — didn’t meet the transfer requirement to a four-year university, filling him again with feelings of frustration.

He persisted, and after four years was accepted into UC Berkeley. But he felt like an “impostor and second-class citizen” as a transfer student, Chida said. He didn’t join any club and made no friends other than a few fellow transfer students. Still, he earned a political science degree with magna cum laude honors. His mother remembers she never cried harder than at his 2007 graduation ceremony.

“Our difficult child became a good child,” Teiko said. “It was a tough time, but good for our family.”

Chida, inspired by McIntyre, would go on to teach third-graders at an underserved public school in New York for three years, but was dismayed by the inequitable access to opportunities his students faced. He concluded he could serve them better with bigger systemic changes.

That’s when he decided to shoot for Harvard Law School, calculating that only an elite credential would give him entry into high-level policy circles.

Before leaving his students for Harvard, he vowed to never forget them or his overarching mission to help young people left behind. So he emblazoned that commitment on his arm — a tree tattoo chosen by his class, which represented the class reading gains charted by Chida.

He clerked for two federal judges, served as an attorney-advisor for then-California Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris for two years and joined Newsom‘s staff in November 2018.

Chida’s parents say they are grateful for American educational opportunities but wish that high school officials had been more proactive in reaching out when their son needed them. Chida’s oldest sister, Mihoko, a veteran educator who has worked in schools in Southern California, Japan and Thailand, said the system utterly failed her younger brother. The family is trying to build stronger bonds after Chida, who lives in Sacramento, persuaded his parents to relocate to Fremont, where his sister also lives; his brother, Ken, is in nearby Union City.

In hindsight, Chida said no single approach can help every child, but a caring and trusted adult reaching out when he first started ditching in middle school and then dropped out in high school would have made a difference for him.

“I didn’t have those relationships,” he said. “I was in crisis and no one noticed or reached out.”

But heroic teachers aren’t enough, he said. Broad, systemic supports are needed to touch all students, and that’s what he’s intent on building with others:

For children to secure safe and healthy foundations — universal preschool, after-school programs, nutrition and other wraparound services. For young people to find meaning in school with promising career pathways — apprenticeships and internships, greater high school access to college courses, more opportunities for low-debt college degrees, greater training in such high-demand fields as education, healthcare, climate and technology.

Chida is also assisting with Newsom’s mental health initiatives, including a $4.7-billion effort to coordinate the health and education systems to better help young people grappling with depression, anxiety and isolation.

He knows that becoming well is a complex, lifelong journey. About a year ago, he began seeing a therapist, taking antidepressants and meditating. He no longer binges on pizza, and is down to 160 pounds. He has come to realize that he has cloaked years of sadness in anger and that men, especially, need permission to feel vulnerable and hurt.

First Partner Jennifer Siebel Newsom, who has launched several mental health initiatives, said Chida’s willingness to share those insights offers a powerful role model, especially for young boys.

“Men like Ben who are willing to share their mental health journey and model positive masculinity are the antithesis to the rampant toxic masculinity plaguing our society,” she said in a statement, adding that many boys and men are flooded with online messages of misogyny and hate.

“On top of California’s investments in best-in-class youth mental health resources, we must also call upon more men to help counter the dangerous narratives that are hurting boys and leading to isolation, and instead model the value of empathy, care, and connection,” she said.

Myrna Castrejón, president of the California Charter Schools Assn., butted heads with Chida and state teachers unions during bitter negotiations over charter school reform legislation in 2019. But Castrejón said she understood his forcefulness and appreciated his ability to disagree respectfully.

“Ben does this work because he anchors himself in his role in drawing from private pain to shape his public purpose,” she said. “Very few people in public service do that with authenticity, and he does.”

::

But baring all isn’t easy, Chida said.

“Having this lived experience … can be the supercharged superpower that drives you forward and motivates you and makes you super passionate,” Chida said. “The flip side of that coin is that it … re-traumatizes you constantly. It makes you feel personally responsible for healing the trauma you went through yourself.”

Nonetheless, Chida plans to share his story more publicly. One of his first forays was a social mobility symposium at Cal State San Marcos last fall, where he tossed aside his prepared remarks to speak from his heart about his year of dropping out and the urgency of helping young people in pain.

Dropping f-bombs, Chida told the audience he wanted raw, truthful conversations. He commanded rapt attention, and some rose at the end to give him a standing ovation.

“I don’t know where this conversation goes,” he said later. “Honestly, it’s scary. But hopefully it makes people feel a little bit better and less alone.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.