The woman in the brightly colored shawl is beautiful. But she does not look happy.

Or, at the very least, she wears a wry expression, one that suggests something in between boredom and belligerence.

Chef Chris Bianco long remembered that look. For years, he wondered what happened to the portrait his father sumptuously rendered in oils over the course of several months starting in late 1969.

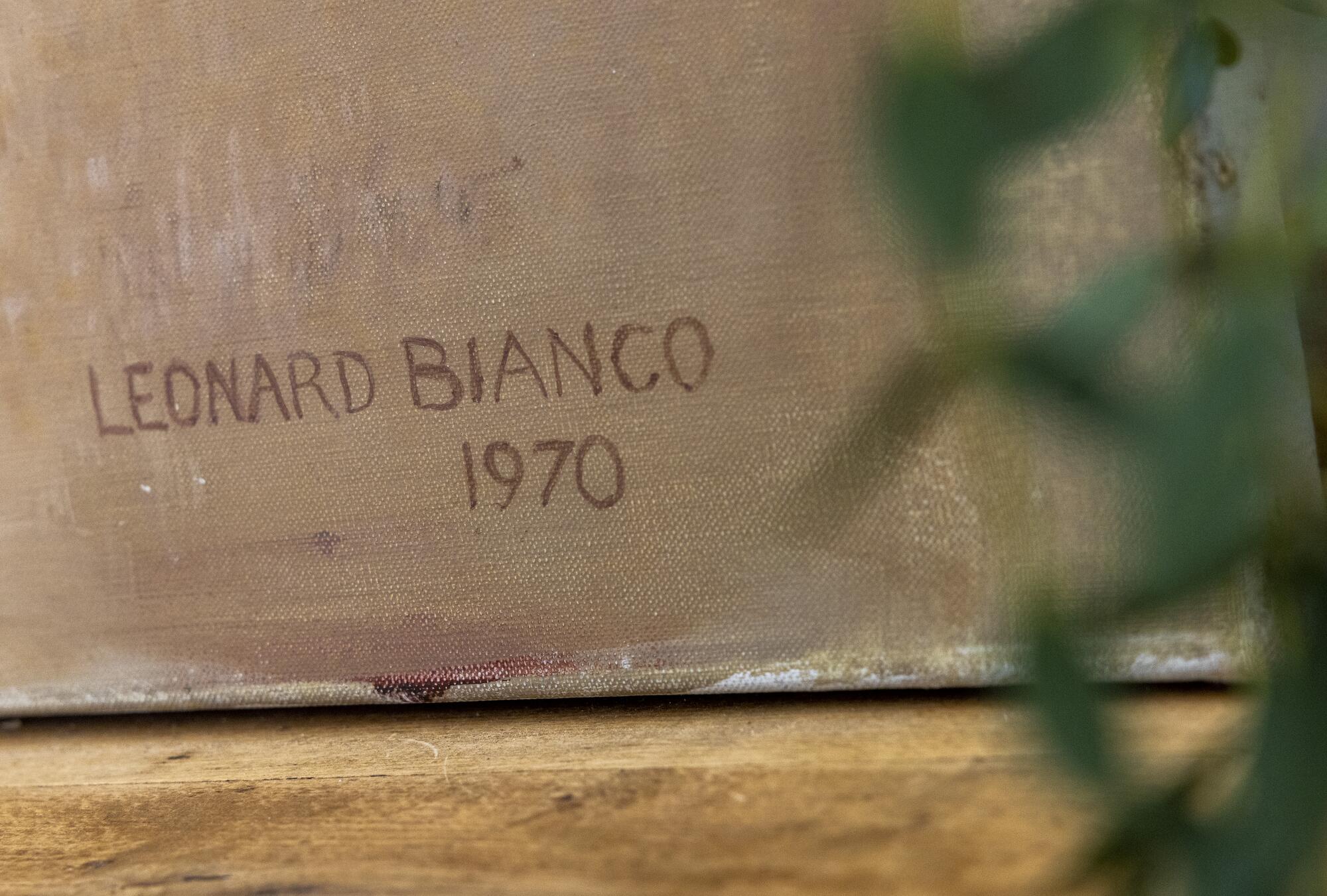

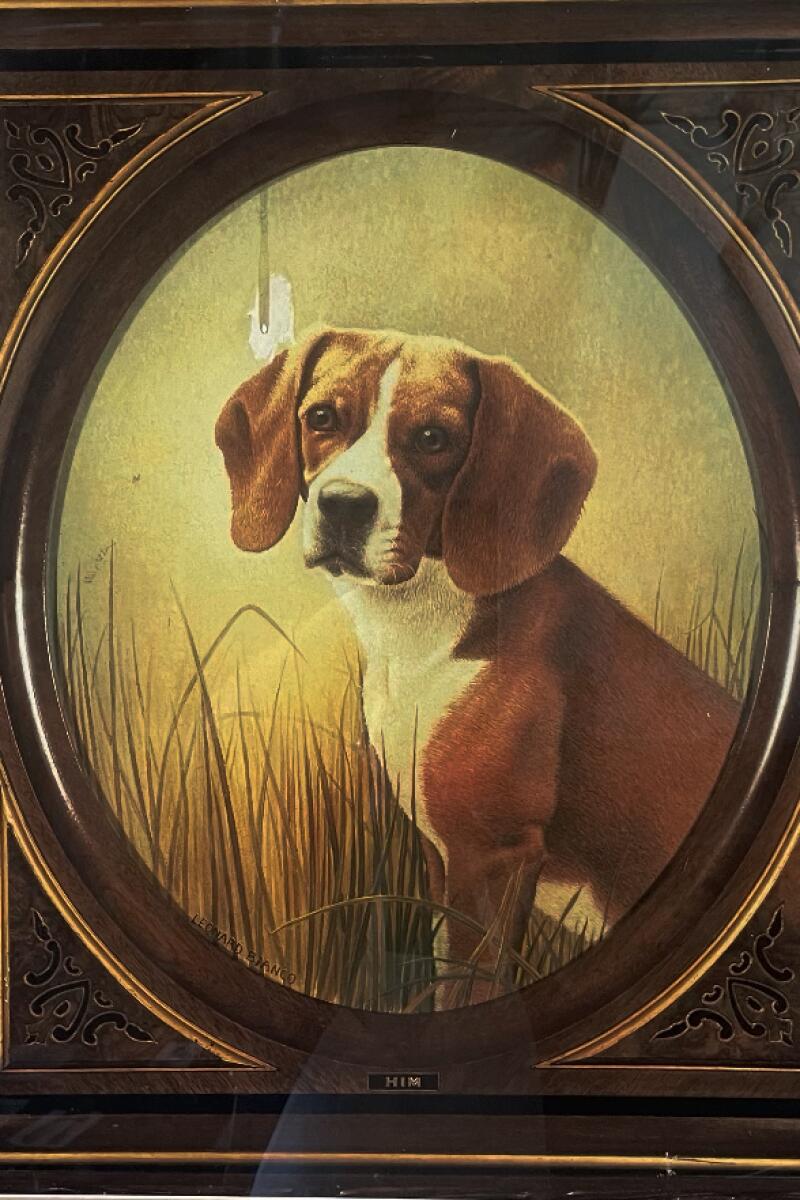

Leonard Bianco was an accomplished New York artist who enjoyed a varied career: Barbra Streisand commissioned him to paint her portrait, and he created a depiction of Christ for the historic St. Maryâs Basilica in Phoenix. He even painted President Lyndon B. Johnsonâs two beagles.

But the painting of the 30-something woman in the shawl â that may have been his masterpiece, said Chris, the James Beard Award-winning force behind Pizzeria Bianco and Pane Bianco at Row DTLA, and four Phoenix restaurants.

For Leonard and his family, though, the portrait was a source of pain, and a kind of stubborn psychic baggage that hovered at the edges of his career. This was the case long after the painting disappeared more than 50 years ago amid an acrimonious dissolution. And it remained so after Leonard died in 2021 at 94.

Then something remarkable happened. Sitting in a brown leather chair at his Phoenix home on a Sunday in April, Chris was scrolling through his Instagram notifications when one caught his eye. He clicked the link.

A photograph showed the painting leaning against a brick building in the New York borough of Queens, beside a trash bag.

âI zoomed in, and my dadâs signature was on it,â Chris said.

He didnât make a sound. Or even move.

âI just stared at it for about five minutes,â Chris said, âand handed my phone to my wife, Mia, to see if I was seeing a mirage or having a dream.â

She confirmed he wasnât.

But Chris was confused. The elegance of the artwork contrasted with the gritty streetscape in a way that was hard to process.

âI couldnât put it all together,â said Chris, 61, arguably the most famous pizzaiolo in the United States.

He hadnât been searching for the painting. But the discovery made him certain about one thing: He needed to get it back. Even if it meant reckoning with the darkness it represented.

Leonard grew up in the Bronx â a âkid from 143rd Street and Willis Avenue,â his son said â and came of age playing stickball in the streets of the borough then known for its large Italian population.

After serving in the U.S. Army during World War II, Leonard began pursuing a career as an artist in New York. He got some formal art education â including studying with American romance illustrator Jon Whitcomb and watercolor master Dong Kingman â but wasnât classically trained. Instead, Chris said, his father had innate gifts, including a dexterity with light and perspective.

Leonard married Francesca Lena in 1959, and they had two children: Marco, then Chris. By then a skilled portrait artist, Leonard also did commercial work, including for a greeting-card company.

Chris was 7 in 1969, when his father got a commission from a well-to-do Manhattan woman. Leonard had just moved the family from the Bronx to Ossining, N.Y., a town about 35 miles outside the city. Heâd bought his first house, and money issues loomed, in part because the life of an artist meant irregular paydays.

âMy dad, like most artists, if you get a decent hit, youâve got to eat off of that buffalo for a long time,â Chris said.

This commission seemed like a good one. But the client had requirements. First, Chris said, she wanted an especially ornate frame, so Leonard had a gold-leaf one fabricated at a cost of $2,000. She paid for it upfront.

Chris said that his fatherâs fee for the portrait was $4,000, about $33,000 today. The artist and his subject struck a handshake deal.

Chris remembers minute details of the roughly four months his father spent toiling over the canvas, which was about 6½ feet tall. He explained, for example, that the intricately patterned shawl wasnât actually a shawl. The woman was pregnant, Chris said, but didnât want that to show, so a window curtain was draped over her.

âItâs one of my favorite parts of the painting,â Chris said.

Leonard delivered the painting to the woman in 1970. Thatâs when things went awry.

She refused to pay, Chris said.

He said his father filed a lawsuit, but nothing came of it. Public records show that Leonard sued the womanâs company in 1971; none of the case details are available online.

âHe just finally gave up on it,â Chris said. âMy dad never got a penny.â

And he never got the painting back.

The result, Chris said, was âa lot of heartache. It made for a tough year.â

It wasnât just about the money. There was something existential about his fatherâs angst.

âTo not get paid for something â at best, it can be confusing,â Chris said. âMaybe they didnât want to pay for it because itâs not good? ... He was very insecure about his work. Which was hard for me to understand, because he was a great painter.â

Still, even after the bitter experience, Leonard included photographs of the painting in his portfolio. It was, after all, undeniably striking. But it seemed like its beauty would forever be tarnished.

Marion Weiss and a friend had just gotten lunch at a pizza place in Hellâs Kitchen and were heading back to her apartment in the Queens neighborhood of Astoria on the afternoon of April 15.

Walking down 35th Street, Weiss spotted something leaning against her building. It was a large painting, she said, next to the garbage and obviously âjust there for anyoneâ to take.

The painting depicted a woman with a brightly colored shawl. âI was fascinated by it â I was just so curious,â said Weiss, 35. âWhere did it come from? Why is it here?â

Studying the painting, whose frame had been removed, she remembered that rain was in the forecast and said to herself: âI canât leave this here.â

So Weiss and her friend carried the painting up three flights of stairs to her apartment. She noticed the artistâs signature and began researching âLeonard Biancoâ on the internet.

Around the same time, Jessica Wolff was learning about the painting, too. She operates Stooping in Queens, an Instagram account that posts images of items left on the street, and one of its followers had just sent in a submission.

Krissy Kivel had seen the painting on the sidewalk and said she âjust stopped dead.â Her apartment wasnât big enough for the artwork, and she hoped that sharing it via Stooping in Queens could help secure it a new home.

Wolff added the painting to the Instagram page. By then, however, Weiss had already snagged it, she said. Before long, the friend whoâd helped Weiss carry the artwork up to her apartment saw the Stooping in Queens post.

This touched off a complex digital choreography â comments were written, direct messages exchanged â but a granular rehashing of the process risks stripping the story of some of its magic. The takeaway: Weiss connected with Chris the next day. The painting, she told him, was safe.

1

2

1. Leonard Biancoâs portrait of President Lyndon B. Johnsonâs beagle Her. 2. Biancoâs portrait of Johnsonâs beagle Him. The originals are part of the collection of the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park in Texas; these prints hang at Chrisâ restaurant Pane Bianco in Phoenix. (Chris Bianco)

âItâs one of the craziest fâ things Iâve ever had happen to me,â he said. âProbably the craziest.â

As they spoke, Weiss said it became clear that the artwork belonged with Chris. He wouldâve paid for it, he said, but she didnât want money. Weiss explained: âIf I was in the same situation, and someone found something that was from my family, I hope they would do the same. It was going to the right place.â

Chris was overwhelmed by her kindness. âI donât know how I could ever show the gratitude I feel,â he said.

Making arrangements to have the painting shipped to L.A., Chris, who splits his time between Hermosa Beach and Phoenix, started to process what had happened. The ordeal over the artwork all those years ago had taken something from his father.

âHe never really, I donât believe, saw his greatness,â Chris said. âItâs an amazing painting. Thatâs what I know â I donât need anybody telling me that. That is a message for people: The best art is what you love.â

A huge wooden crate arrived in Los Angeles in late September. Chris pried it open and looked at the face he knew from photographs.

âIt was surreal,â he said.

It was hard to square the womanâs beauty with the ugliness of the episode. But taking possession of the artwork offered a measure of recompense.

âJustice may not happen in our own lifetime,â Chris said. âSometimes things donât happen overnight, but ... eventually, ârightâ finds its way.â

Chris asked that The Times not name the woman in the painting, because doing so could detract âfrom the overall message that this was a bad circumstance that turned into a really goodâ one. Reached by The Times, the woman, now in her 80s, confirmed in a brief telephone conversation that she was the subject of the painting but otherwise declined to comment.

Still, a mystery endures. How did the portrait end up on the street in Queens? There are theories. Weiss wondered if the woman or a family member had lived in her building. But the woman and her children havenât lived there or nearby, according to online public records.

Thatâs not Chrisâ focus. For him, the experience has revealed a lesson to be shared with his three young children: âSometimes we just have to hang around long enough. We donât need to make voodoo dolls of people or wish bad upon them. We just got to hang around and present kindness.â

The experience has been a gift in more ways than one.

Chris and his father had a tradition tied to the opening of the chefâs restaurants: Leonard would create a painting for each one. It was a ritual dating back to the 1994 debut of Chrisâ first sit-down spot: Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix.

There was no way to continue the tradition at Pane Bianco, which opened in June, two years after Leonardâs death.

But on what was once a blank wall just off Pane Biancoâs open kitchen, the woman in the brightly colored shawl now looks out across the restaurant. During a recent afternoon, none of the diners seemed to meet her gaze. But Chris did.

âHer external beauty was a billboard for my dadâs work,â he said. âShe paid it forward â she lent her image. Now itâs mine to share with others.â

If the woman owed Leonard, Chris or any of the Biancos anything, that debt has been settled.

âSheâs paid in full,â he said. âWeâre good now.â

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.