- Share via

The search for answers played out in a Rowland Heights home, in a room the owners use for karaoke. On this day, it was the stage for reenacting the worst mass shooting in modern Los Angeles County history.

Full-length mirrors covered a wall. Chinese lanterns hung from the ceiling. A disco ball reflected light on the tile floor below. And a middle-aged Asian man, head in hands, dispelled the mystery that hangs over Monterey Park to this day: why a 72-year-old would shoot 11 people to death, turning a celebration into a bloodbath and shattering a tightknit community.

“I’ve thought about suicide and even thought about killing someone, because I often hear voices in my head telling me to kill someone,” Kaidy Kuna told his friend.

But Kuna is an actor. And on this Saturday he was rehearsing a play called “Dance with New Year’s Eve.” His character, AhGen, was written to parallel Huu Can Tran, who fired 42 rounds in the Star Ballroom Dance Studio during a Lunar New Year’s Eve celebration before taking his own life.

The play was created with limited input from those tied to the Jan. 21 Monterey Park massacre — and despite the concerns of many survivors. Its aim is to help a community struggling to heal and grappling with the unknowable.

Because when mass shooters die, the answers often die with them.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department investigation remains open, with no clear sense of when it will be over. A letter recovered from Tran’s home — written in Chinese and addressed to law enforcement — has yet to be released.

Investigators handed over Tran’s letter, surveillance video, witness and victim statements and other evidence to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit to determine a motive and complete a post-shooting analysis. The FBI declined to comment on the letter.

“Do you remember at the very beginning when all these things happened?” asked Lloyd Gock, who survived the shooting by hiding under a table. “The police already said that the truth may probably never come out. We’ll probably never know why he did it...

“We can only guess.”

Like the character meant to parallel his life, Huu Can Tran lacked a sense of belonging.

He was born to a wealthy family in Vietnam five years before war tore the country apart. He told his friend William Chen that, as a teenager, he had chopped a person’s hand off during a fight. His family sent him to Taiwan to avoid jail.

Tran studied electrical engineering, but he told a former friend that he also got in trouble, joined a gang, kidnapped people. He moved to Hong Kong, but he stayed in the gang life there.

At least that’s the story Tran told.

He was considered the “black sheep” of his family and fell short of expectations, according to his former friend, who did not want his name linked to Tran. So fraught was the relationship that his father once threatened to cut him out of his inheritance.

Investigators continued to puzzle over what pushed Huu Can Tran to carry out a mass shooting at a Monterey Park dance studio, focusing on the possibility he was driven by jealousy.

Life in the U.S. wasn’t any easier for Tran. He lived in Texas for years before moving to Southern California, where he bought a small, white stucco home in San Gabriel in August 1989. He bounced from job to job, working as a carpet cleaner, at a supermarket, as a delivery driver for an auto parts company and a property manager for an apartment complex in Arcadia.

The same year he submitted a petition for naturalization, 1990, a San Gabriel police officer arrested him after patting him down and finding a loaded RG40 .38-caliber revolver. He had been trying to notify police that a nearby liquor store had been robbed at the time of his arrest, according to a police report.

Dancing was the bright spot in Tran’s ordinary life. He was proud of his abilities, boasting to friends that he’d been professionally trained in Texas.

Star Dance was one of his favorite places. It’s where he met Chen around the late 1990s; they visited the studio at least three times a week. Tran, who went by Andy, danced with partnerless women, a grin at times splitting his face from ear to ear.

“Andy always had a smile on his face, and he was friendly to other people,” Chen said. “He liked to make friends.”

The studio is where Tran met his future wife. They married in June 2001. The following year, he started Tran’s Trucking Inc., registering the company in San Gabriel and working as a driver.

But his life began to unravel. He dissolved his company in 2004 and filed for divorce a year later. He had told his former friend that he didn’t get along with his ex-wife’s family and had secretly made audio recordings that he threatened to use against her in the divorce. Tran’s ex-wife did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Eric Chen, a San Gabriel pastor, tried to help survivors get access to resources and encouraged them to seek counseling after the Monterey Park mass shooting at Star Ballroom Dance Studio.

Through it all, Tran kept dancing.

He offered to teach women how to ballroom dance for free, according to his former friend. But he had two requirements: They had to show up every day. They could only dance with him.

Shally Ung, who started going to Star Dance in 2006, said a friend complained Tran was too controlling. Eventually her friend quit dancing with him. She warned Tran that, if he kept it up, he wouldn’t have anyone left to teach.

Tran often complained about the studio’s Chinese dance instructors. He said they were hostile because he was stealing potential students, which meant a loss in revenue. He also complained to his friends about Ming Wei Ma, the studio’s former manager.

Chen noted a growing sense of paranoia in his friend, evidenced by Tran’s fears about his family. He told Chen they were going to kill him. He was frightened of his brother and wove tales that Chen said seemed irrational.

He changed his phone number every month, Chen said, and believed people were listening in on his calls.

“He always had a problem of the mind,” Chen said.

Eventually, Tran stopped going to Star Dance. After he sold his San Gabriel home in 2013, Tran told Chen he was going to drive around and live out of his van.

The ensuing years are a mystery to those who knew Tran. Some heard he had gone to live with his brother in Northern California.

A gunman opened fire at a Monterey Park dance studio late Saturday, killing 10 people and wounding 10. He went to another dance studio in Alhambra but was disarmed by two people and later killed himself in Torrance.

But in the first weeks of 2023, nearly 100 miles southeast of Star Dance, his life was barreling toward darkness.

He lived at the time in a mobile home in Hemet, where he stockpiled hundreds of rounds of ammunition, along with supplies to make suppressors that muffle a firearm’s blast.

He twice visited his local police department, accusing his family of fraud, theft and poisoning, crimes he alleged had happened in L.A. decades earlier.

He said he’d come back with proof. He never did.

Twelve days after his last police visit, on Jan. 21, Tran returned to Star Dance.

Gone was the smile captured in a photo from the old days and in the memories of people who had once shared the ballroom with him. That night, he looked haggard, aged beyond recognition, according to surveillance video and witness accounts.

He carried a modified Cobray model CM11-9 pistol.

First, he killed Mymy Nhan, 65, in the parking lot. Then he went into the studio, where he fired 42 rounds over several minutes. Eleven people died. Nine others were injured.

Then he headed to Lai Lai Ballroom & Studio in Alhambra, where he had also once danced. Brandon Tsay, whose family owns the studio, wrested the gun from Tran’s hands.

Twelve hours later, Tran sat in his van in a Torrance parking lot. Officers closed in on him.

He turned his gun on himself.

On a Friday afternoon in a cramped room in Temple City, Tuen-Ping Yang coached the star of “Dance with New Year’s Eve” on the character he would need to become.

“We put the gunman’s background in you,” he told Jonathan Lim, the actor playing AhGen in the Mandarin version of the play.

“The audience, do they know?” Lim asked.

“They don’t know,” Yang said, with a shake of his head. “They will not know.”

Yang is the executive producer of the controversial play, which he also helped write. It will be performed by two different casts, in English and Mandarin, ending on the anniversary of the Monterey Park massacre.

The play revolves around AhGen and Linda, a couple who lost contact after AhGen emigrated to the U.S. The onetime lovers encounter each other more than 30 years later at a Lunar New Year’s Eve celebration at Star Dance, where AhGen tells Linda about his failures in America.

Like Tran, AhGen is an immigrant. They share mental health struggles. He too bought a truck and worked as a carpet cleaner. He and his wife split up and also never had children.

AhGen tells Linda that he called 911 to turn himself in three months earlier because he believed the FBI wanted him to kill President Trump.

“I always thought you took all my savings and ran away to America, avoiding me,” Lee Chen said, reading the role of Linda during a rehearsal for the play’s English version. “I didn’t realize you went through so much suffering.”

Yang, the director, interrupted the actors to remind Chen of the importance of this scene, intended to redeem AhGen in the audience’s eyes.

“Make him from a bad person, become a good person,” Yang said, before resting his hands on Kuna’s shoulders as the actor crouched on the floor. “At this moment, the audience will be on his side. It’s very important.”

By the end of “Dance with New Year’s Eve,” AhGen and Linda will be shot to death.

Yang began to imagine the play weeks after the Star Dance shooting.

When he first floated the idea of bringing the tragedy to the stage, Maria Liang, the owner of Star Dance, shut him down. Weeks later, he tried again, telling her “it’s for Chinese people. For our next generation. ... We want people to remember.” Liang eventually agreed.

Angela Sheng, president of Elite Performing Arts Group USA, which is staging the performance, said she and Yang talked to about 20 people as they worked on the drama, including survivors and Liang.

A survivor named Gao, who asked to be identified only by her last name because of safety concerns, is among the performers. Tran had given her free dance lessons a decade ago. As he reloaded his gun during the shooting, she said, she ran for safety through the studio’s side exit.

“I want to participate because it will alleviate my sadness, stress and help me get out of the shadow of the shooting,” Gao said.

The performance will consist of three parts: 70 minutes of a play; about 20 minutes of the survivors telling their own stories, along with news footage of the shooting; and about 40 minutes of music, with a choir and dancers.

Nearly a dozen cameras will record the show; Yang hopes to make it available on streaming platforms.

As the play came together, Yang said, people in Monterey Park were divided into two factions: those who wanted it so they could remember the victims, and those who felt the play would be traumatizing.

Yang said he’s directing it to remember the lives of “11 innocent people he killed with no reason.” He also wants to let people know Chinese Americans are part of the U.S. just like everyone else.

“It’s a mass shooting in our home, our community. We don’t know what’s the reason. ... But he killed people. That’s the truth,” Yang said. “So please remember this happened.”

Eleven people are dead after a man opened fire in a dance studio in Monterey Park. Police believe the shooter also targeted an Alhambra studio. Here’s what we know.

Liang showed her support for the play at a news conference last month in Pasadena. Although she wasn’t at the ballroom during the shooting, her brother was shot in the arm. She lost Ma, her “best friend” and “public relations manager,” as well as treasured clients.

Liang — who emigrated from China — said she knows and trusts those who created the play to tell the story of Star Dance, which she called a “social hub” for many Chinese immigrants. She plans to speak on stage about that night.

The play can’t explain why Tran shot up the ballroom, Sheng said. But the story is about immigrants and what happens when their dreams die.

It’s also about isolation and loneliness, she said, referring not just to what happened in Monterey Park but also to a mass shooting in Half Moon Bay that occurred less than 48 hours later. In that case, 66-year-old Chunli Zhao, who emigrated from China more than a decade earlier, killed seven people.

“That … led us to think it’s a big problem,” Sheng said. “Elders and their isolation, so we want to raise that awareness.”

Shally Ung spun her dance partners, Soo Wong and Sally, across the tile floor, leading them in the cha-cha-cha and rhumba on a recent Thursday.

They joined more than 50 others for the first ballroom dance workshop at the MPK Hope Resiliency Center, which opened in August to help survivors and community members who are grappling with the shooting.

Along with their love of dancing, Ung, Wong and Sally shared something else: They all survived the Star Dance massacre.

During the shooting, Ung, 58, lost Andy Kao, her decades-long dance partner; Sally had been grazed by bullets; Wong, 69, lost her best friend, Diana Tom. Sally asked not to be identified by her full name due to safety concerns.

It had taken Ung four months to begin dancing again, and then only after she started seeing a psychologist. She initially resisted mental health treatment; her husband encouraged her to go. She’s now completed 16 sessions.

“It’s helping,” Ung said. “After that, I relaxed a lot.”

The horror of that evening felt far off as the women danced with ease borne of years of practice. Ung’s crystal-embellished pants glittered as she moved across the makeshift dance floor; they were the same pants she’d worn the night of the shooting.

She knew the men’s and women’s dance steps and spent the four hours partnering with her two friends. When she caught a break, she sank into a chair and fanned herself with a napkin.

“I’m so tired,” she said, sighing. But she spent most of the afternoon smiling.

As the event wound down, Yang arrived with fliers in hand. He wanted to ask the survivors in attendance if they’d be open to sharing their stories of that night on stage. Initially Wong, Ung and Sally agreed. But after Yang left, as they sat down to talk it through, their feelings shifted.

“Originally we thought the play was to lift up spirits. But listening to it, it’s like reenacting the trauma,” Ung said in Cantonese.

“Always repeating it. I’m not mentally prepared for it,” Sally said. “I don’t want to think about that day.”

By the end of the conversation, the women had decided not to participate.

The same concerns have played out among other survivors and families of the deceased, who expressed frustration that they have not been able to read the script to better understand the play.

Gock, a survivor, also questioned where the money from ticket sales will wind up; some tickets cost more than $200. (Yang said the performing arts group has invested more than $100,000 in the play and will likely lose money, “because we don’t know how much tickets we can sell.”)

“I think it’s very distasteful to try to remind people what happened or reenact what went on,” Gock said. “It’s not a funny matter. It’s gonna bring up a lot for people.”

Fonda Quan, whose aunt was the first person killed outside Star Dance, said her family hasn’t been contacted or asked for their input. She said she was under the impression that a lot of survivors and even those injured would be involved.

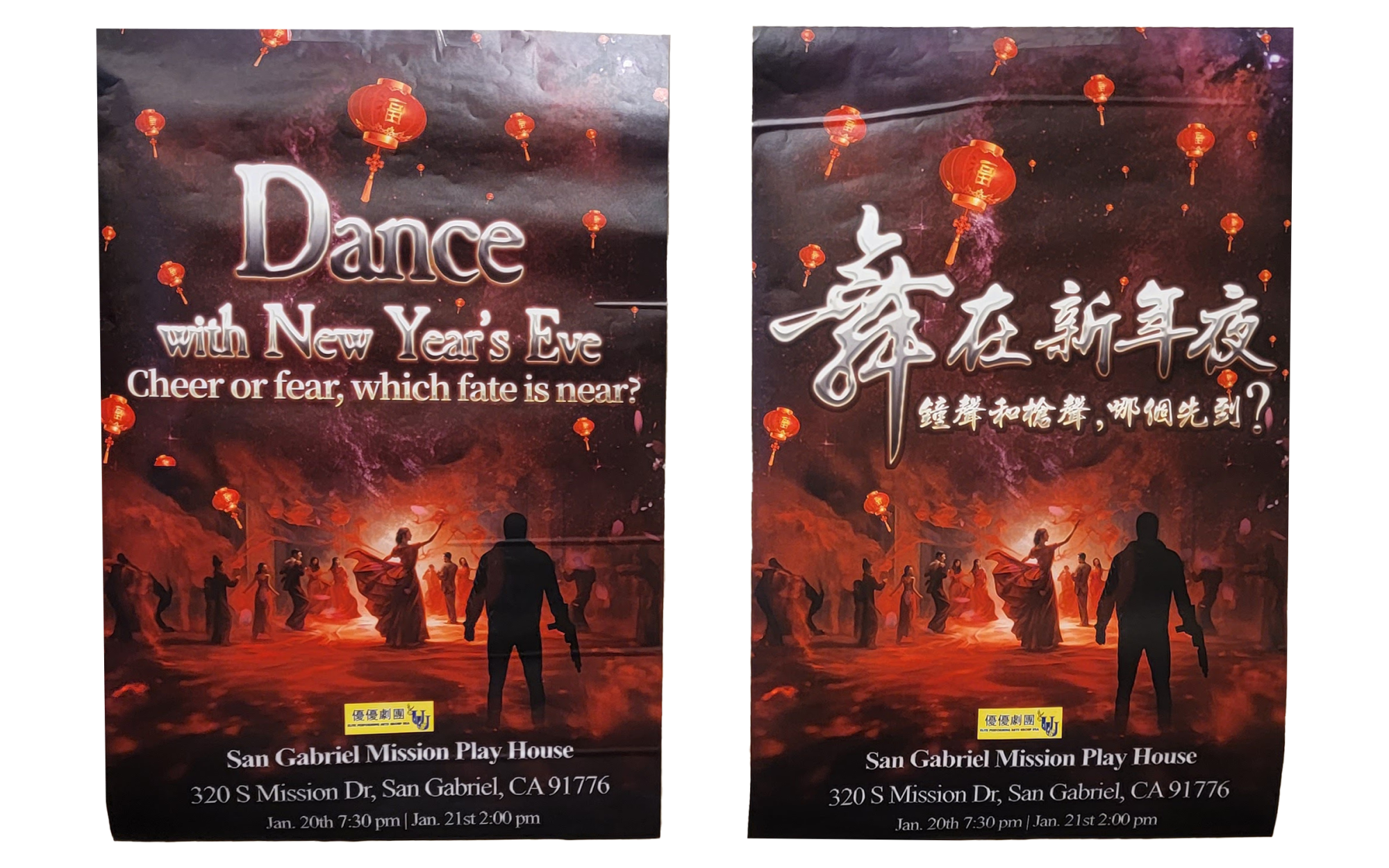

Kristenne Reidy, whose father, Valentino Alvero, was killed in the shooting, said she found the flier for the play — which reads “Dance with New Year’s Eve Cheer or Fear, Which Fate is Near? — to be “too on the nose.” It depicts silhouettes of dancers and partygoers at a Lunar New Year’s Eve celebration and a man lurking in the foreground holding a gun. A Chinese version of the flier reads: “Which will come first: The sound of bells or gunshots?”

She and her father’s friends had nightmares after the shooting, she said, adding: “I can’t imagine for the people who were actually there to have to see this flier.”

The play was initially presented to Reidy as a ballroom dance performance, which she fully supported. Then, she heard secondhand that one of the protagonists is meant to represent Tran. Reidy no longer supports the play and said she doesn’t plan to attend.

“The intention, I think, is good. We want to see everybody as a human being. This man was also an immigrant and was part of the immigrant community, and there is this idea of forgiveness and humanizing him, because he was human,” she said. “But he also made the decision to kill my dad and those people.”

Instead of attending the play, Reidy said, she and her family will pray at her father’s grave.

For months, a banner on Garfield Avenue, a block north of the building that housed Star Dance, read “United We Dance” in memory of the massacre.

Today, a red banner for the January Lunar New Year Festival hangs in its place.

The city has reverted to a sort-of normal — although the mass shooting has permanently marked many here, including first responders.

Out of 17 firefighters at the scene that night, two remain on extended leave, said Fire Chief Matthew Hallock.

The department has provided peer counseling and mental health services to its staff. But with the one-year anniversary nearing, Hallock said, there will be “setbacks.”

“There was never going to be a quick fix,” Hallock said of the department’s recovery process. “This was the call that had such a tremendous impact on the first responders.”

Lt. Bob Hung, a 15-year veteran of the city’s Police Department, was among a half-dozen Chinese-speaking police officers who responded to the 911 calls and talked to dozens of survivors, victims’ relatives and bystanders who didn’t speak English or felt more comfortable with Mandarin or Cantonese.

Inside the ravaged studio, he listened as cellphones rang, owned by people who would never answer them.

It fell on Chief Scott Wiese to ensure his officers were getting rest. He spoke with officers individually the night of the shooting to see how they were feeling.

“Everybody was emotional. They are human beings. None of them had ever seen that level of trauma before,” Wiese said. “They understood the impact it was going to have on the community.”

In the months that followed, each officer handled the trauma differently, the chief said. Some talked to their families. Others talked to their peers. Some didn’t want to talk at all.

Wiese said he tried to make sure his officers had therapy and peer support available. Most took advantage of the help, he said.

No one has left the department in the aftermath of the shooting. No officers requested leaves of absence, even though the department offered them.

The police chief acknowledged that the community “will never know the complete reason” behind the shooting.

“We can speculate all we want,” Wiese said, “but no one will ever know, because no one got a chance to talk to him about what he did.”

Hung said it’s normal for people to look for explanations. But heading into the anniversary, he also wants people to think about those who lost loved ones.

“The burden that we carry is very small compared to what those family members have to carry,” he said.

Since that day, they — like Americans across the country — have watched in horror as gun violence continues unabated.

In nearby Orange County, where a retired Ventura Police Department sergeant killed three people at a bar. In Lewiston, Maine, where a gunman killed 18 at a bar and a bowling alley. Most recently, on a university campus in Las Vegas, where an academic fatally shot three people.

Councilmember Henry Lo, who served as the Monterey Park mayor at the time of the shooting, called the mayor of Lewiston after the October attack there. Lo had attended Colby College, about an hour away from the city.

“This seems to be a very uniquely American phenomenon,” Lo told The Times. “It seems like, when we try to have a conversation, we all go into our little quarters, and it comes down to: Are you against the 2nd Amendment or what can we do to stop having” mass shootings.

“What we can’t allow to happen is for people to suggest just move on and say this happened and there’s nothing we can do,” he said. “We have the responsibility to make sure that we are part of the conversation and then we will not forget.”

All signs of the Monterey Park massacre have long since been cleared away. The space that housed the studio sits empty, chairs and tables gone. There are no plans to open another business there anytime soon.

It is unclear whether Star Dance will reopen in a new location.

But on a stage in San Gabriel next month, in a Star Dance of the imagination, music for dancing will play once more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.