Anne Cusack Derk, Times photographer of skill and heart, has died

Chicago in the late 1970s and 1980s overflowed with a cadre of smart, keen-eyed photojournalists who would go on to win national acclaim, taking unforgettable pictures from their hometown and hot spots around the world.

They worked for the Chicago Tribune, the Sun-Times and other newspapers, competing fiercely for the best images before adjourning for liquid therapy at the Billy Goat Tavern, a storied journalism watering hole.

More than holding her own in this remarkable company was a young photographer named Anne Cusack Derk. She was something of a unicorn â frequently the lone woman in the bullish fraternity of Chicago news shooters.

Known for both her vivid picture-making and her abundant heart, Cusack became the first woman honored as Photographer of the Year by both the Illinois Press Photographers Assn. and, twice, by the association of news photographers in Chicago.

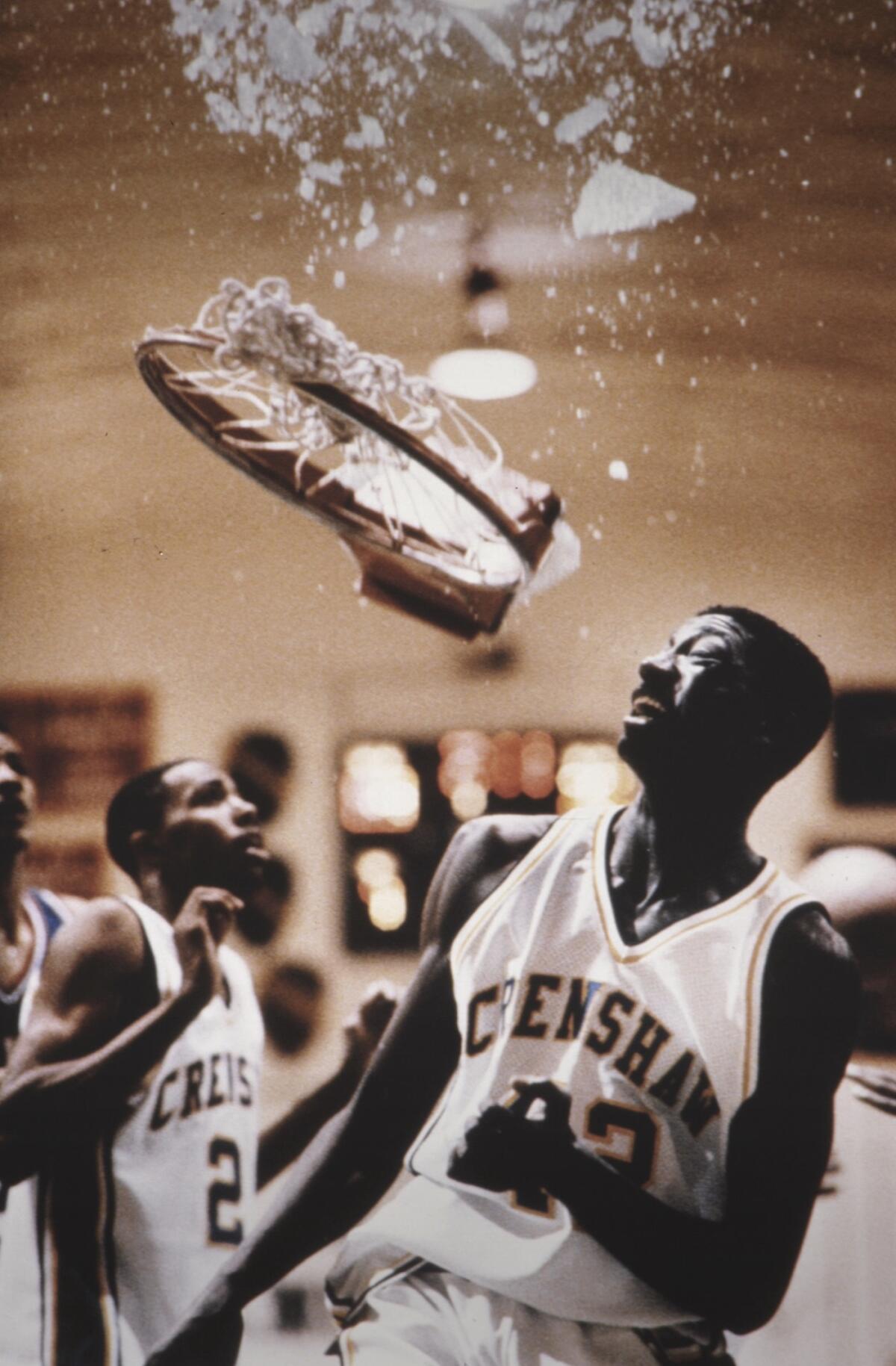

Cusack later took her intimate storytelling to The Times. In a career that spanned five decades, she won renown for photos that captured the anguish of Vietnamese boat people on the South China Sea, the grit of a âgirl boxerâ from L.A.âs Eastside and the ferocity of a backboard-shattering dunk by a high school basketball player.

Cusack, who retired from The Times in 2015, died Monday, with her two daughters at her side, at Los Robles Regional Medical Center in Thousand Oaks. She was 72 and had struggled with interstitial lung disease since 2019.

Her colleagues remembered her as a trailblazer, a woman who made award-winning images while raising three children with her husband, Richard Derk, a former photo editor at The Times.

âShe met the world with an open, loving, unguarded heart,â a dear friend, Nancy Drew, wrote in tribute to Cusack. âIt was the key to her art. As a news photographer she walked into situations both grim and delightful, and came back with award-winning images.â

Like many news photographers, Cusack was called on to shoot an array of images, from news conferences to murder scenes. Her skills came into highest resolution on projects, including her nearly two-month foray to Southeast Asia to catalog the suffering of Vietnamese refugees. At one point, she jumped into a dugout canoe, the only vehicle that could get her to a remote island where many people were stranded. In a relentless rain, she held an umbrella in one hand and a bucket in the other. Years later, Cusack would laugh while recalling her guide, who repeatedly admonished: âKeep bailing! Keep bailing!â

While she captured wrenching images during that assignment for the Chicago Tribune, the newspaper had not yet fully embraced photo essays and initially published only a handful of her pictures. So Cusack set to work with her husband to design a five-page layout of the photos. The presentation was so compelling that the Tribune ran all five pages.

âOne thing that came out of it was a kind of awakening at the paper of the power of photojournalism,â Derk recalled.

Some of his wifeâs most compelling work for The Times came when she collaborated with Kurt Streeter, a gifted writer who is now a national correspondent for the New York Times.

The duo first worked together on a series about a slight young girl from L.A.âs Eastside who yearned to become a boxer. âThe Girlâ recounted the journey of Seniesa Estrada and her father, Joe, delving deeply into issues of race and identity.

Cusackâs photos captured the girl and her sport in all its savagery and tenderness. One gripping image showed Seniesa, her eyes gleaming with desire, reflected in the glass pane over a poster of Muhammad Ali.

Cusack and Streeter would team on three other projects that delivered harpoons to the heart. One followed identical twin boys struggling with heart disease. Two other projects centered on young women with traumatic medical conditions: one an Iraqi disfigured by a war-time bomb, the other an American who suffered a horrendous brain injury in a car accident.

âShe was so much more than a photographer,â Streeter said this week. âShe was a reporter right there with me, with a special ability to make people feel at ease. It was like having a motherâs wisdom and care and strength at my side. That always helped so much in these highly emotional situations.â

Not surprisingly, Cusackâs caring persona took full force in her home life.

Her three grown children remembered her as the mother who guided and inspired by example: driving home from work, she told one daughter to stay in the car as she donned fire gear and jumped out to shoot a brush fire; helping prepare her kids for âCrazy Hair Dayâ in school, her creativity conjuring up just the right hairdos; and consoling her teenage son, jilted by a girlfriend, by lying on his bed and finding the right words.

âAnne trailblazed that path for so many women, and beautifully captured the essence of people and what it meant to be human,â daughter Gwendolyn Derk, a physician who lives near Portland, Ore., said in a Facebook post.

Anne Cusack was born in Chicago in 1951 and grew up in the northern suburb of Glenview. She attended the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where she fell in love with another Daily Illini photographer, Richard Derk.

âAnnie,â as friends called her, would become the first woman photo chief at the college paper. She graduated in 1973 with a degree in social work.

Cusack worked at small papers, mostly in suburban Chicago, before landing in the big time: the Chicago Tribune, where she was a photographer from 1978 to 1990. Among the luminaries shooting pictures in Chicago in those days were John White, a Pulitzer Prize winner for the Sun-Times, and Pete Souza, later chief White House photographer for President Obama.

Perry Riddle, another member of the Chicago cohort, landed a job as a photo editor at The Times, and in the 1980s he brought other members of the group to the paper, including Al Seib and Rosemary Kaul. The Times offered jobs to both Derk and Cusack, who moved to Thousand Oaks.

Richard Derk said the humanity that so many colleagues and subjects admired in his wife was not a âtactic.â

âOn a story, she would just become part of someoneâs circle, become part of someoneâs family,â Derk said. âIt wasnât a journalist working their way in there. She was very much a student of the human condition.â

After leaving The Times, Cusack put her creative energies into new passions, particularly sculpture. Diagnosed with the lung illness in 2019, it became harder for her to remain active. But she was thrilled that she got to attend the wedding of her younger daughter, Maggie, in October of last year.

The family plans a showing of Cusackâs work in Thousand Oaks and a burial in Glenview, Ill. She is survived by her husband, two daughters and son, George, and two grandchildren, Miles Tucker Derk and Paul Richard Derk.

This week, the Derk children remembered their mother as someone who urged a certain wonder about the world.

Maggie, a transportation planner who lives in the greater Portland area, recalled a night in their childhood when her mother woke the two Derk girls in the dead of night. Though it was past 2 a.m., she lay them down on a blanket on the lawn to watch a meteor shower.

To this day, the sisters recall one particularly giant celestial object. The meteoroid appeared so enormous they are sure they heard it roaring across the heavens.

âWe just had a blast, laying out there in the dark together,â Maggie Derk said. âWhen I see a shooting star now, I will think of her.â

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.