L.A. County COVID-19 deaths hit a new winter high. Why?

The number of COVID-19 deaths reported weekly in Los Angeles County has hit the highest point of the season, underscoring the continued deadly risks of a disease that has ripped through the community for nearly three years.

L.A. County recorded 164 COVID-19 deaths for the seven-day period that ended Wednesday, a new high that exceeds the summer peak of 122 deaths for the week that ended Aug. 6. That tally was the worst in 10 months. The rolling weekly death tally declined slightly for the week that ended Thursday, to 163.

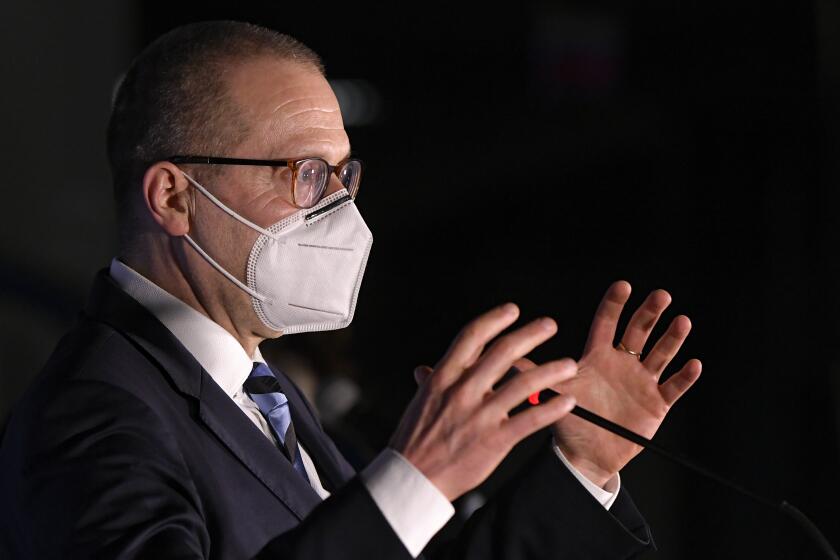

âDeaths are high, and itâs really upsetting,â L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Thursday. Nationally, many more people are still dying from COVID-19 â about 36,000 since early October â than the flu â estimated to be about 14,000 over the same period.

But the distressing development comes even as other metrics show a relatively promising picture. L.A. Countyâs latest death tally is a fraction of last winterâs maximum, when 513 deaths were reported for the week that ended Feb. 9.

The number of coronavirus-positive patients hospitalized statewide and in L.A. County has remained substantially lower than last winter and is showing early signs of decreasing from a potential early winter peak.

A feared COVID-19 wave that officials warned could crest following travel and gatherings over the winter holiday season has also failed to materialize. Case rates in L.A. County and across California have fallen in recent weeks, as have coronavirus levels in wastewater.

The latest Omicron subvariant, perhaps the most infectious yet, has gained a foothold in California. Officials say its growth advantage is worrisome.

COVID-19 âdid seem relatively flat over the holidays,â State Epidemiologist Dr. Erica Pan said during a webinar Tuesday, and officials are hopeful âweâre out of the woods and out of the worst for this winter season.â

Ferrer also expressed optimism that cases are declining. L.A. County reported 1,857 cases a day for the week that ended Thursday, down 19% from the prior week. On a per capita basis, thatâs 129 cases a week for every 100,000 residents. A rate of 100 or more is considered high.

The peak rate this fall and winter was 272 cases a week for every 100,000 residents, recorded the first week of December. Over the summer, cases peaked at a much higher level: 476 a week for every 100,000 residents.

The California Department of Public Health regularly estimates the effective reproductive number of the coronavirus. For roughly the last month, that figure has been below 1.0 in L.A. County, which indicates transmission is either stable or decreasing.

âWe donât know how the upcoming months will look in terms of COVID,â Ferrer said. âWe know the pandemicâs not over. However, we have likely entered a new phase, in part because of the tools now available to blunt the impact of COVID and in part because of the choices people in L.A. County are making.

âMy hope is certainly that we continue to report lower numbers and that transmission is significantly lowered in the weeks ahead,â Ferrer added.

Still, the recent increase in deaths is concerning. L.A. County has seen more weekly COVID-19 deaths this winter than last summer, despite having significantly fewer coronavirus cases officially reported.

A World Health Organizationâ official says the agency sees âno immediate threatâ for the European region from a COVID-19 outbreak in China.

One obvious culprit is the continued proliferation of at-home tests, the results of which are not reliably disclosed to public health authorities. The extent of this reporting gap is impossible to know, but some officials estimate the number of infections is roughly five times the official counts.

The countyâs autumn low was 43 COVID-19 deaths in the first week of November, which rose to 153 for the week that ended Dec. 23. Weekly deaths temporarily declined but then rose after winter break, posting new seasonal highs this week.

Itâs unclear why deaths are higher than in the summer, and Ferrer said the county will probably have to review medical records to see what trends emerge. One possibility is that people dying from COVID-19 more recently were also sick with other respiratory viruses, such as flu and RSV, that werenât circulating as widely earlier.

Another explanation could be that older residents are more vulnerable because they are far removed from a prior infection or vaccine dose. Only about 38% of eligible county residents 65 and older have gotten the updated bivalent booster â available since September â a figure Ferrer called âsobering.â

A preliminary study in Israel finds that seniors who received an Omicron-targeting booster shot were 81% less likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 than those who skipped it.

âWe believe that we could prevent more deaths, certainly more hospitalizations as well, amongst older people if we could increase the rate of uptake on the bivalent boosters,â she said.

Older residents are also more likely to have underlying health conditions that put them at higher risk of developing severe illness from COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses, Ferrer noted.

Itâs also possible that the strains that are circulating now are causing very mild illness for most people, âbut for older people, and people who have serious underlying health conditions, [it could be] leading to more severe illness.â

One thing is certain, though: Older and poor residents are being hit especially hard by COVID-19 deaths, according to county data.

People 80 and older are nearly five times as likely to die than those 65 to 79. And people in the latter age group are five times as likely to die than those 50 to 64, according to county data for the three-month period that ended Jan. 3.

Mild cases of COVID-19 can cause patients to suffer long COVID symptoms, and a new study finds that some of those symptoms can linger for more than a year.

âThis emphasizes the extra risks that older age groups face. And it does underscore the importance of protections against COVID-19, especially if youâre around people who are at risk of more severe illness, and your risk ... of transmitting to someone older,â Ferrer said.

That California encountered a COVID-19 surge thatâs considerably milder than the prior two winters is promising.

âMy sense is that we have more immunity thatâs really helping us particularly avoid hospitalizations for lots and lots of people,â Ferrer said. The increased immunity includes the more than 80% of residents who have completed their primary vaccination series, including people who have received one or more booster shots.

Ferrer also said she thought more people were taking preventive measures than a few months ago. âI see a lot more people wearing masks, certainly on airplanes,â Ferrer said, recounting that on a flight she was on, 1 in 3 passengers were masked.

But the next few months are still uncertain.

Officials have warned that the rise of a new coronavirus subvariant could threaten to reverse trends, as has happened several times.

The Omicron subvariant XBB.1.5, perhaps the most infectious strain yet, has gained a foothold in California â and its spread could send case counts climbing.

âIt has a relatively high growth rate advantage. It does have this mutation that has even more immune evasion,â Pan said of XBB.1.5. âSo we do expect it will gradually become the more predominant strain in California.â

The new subvariantâs implications remain unclear, Ferrer said.

âI think the question on just about everyoneâs mind is how concerned should we be about XBB.1.5? I suggest we should be cautious. Itâs a new strain. It spreads rapidly and it can evade prior immunity. However, I donât think anyone has a clear picture yet of what the impacts will be,â Ferrer said.

Some areas have seen hospital admissions rise seemingly in concert with proliferation of the variant, but that hasnât been the case everywhere.

âThereâs not yet clear data or patterns,â she said. âAnd it may be that XBB.1.5 doesnât fit into the patterns that weâre used to seeing.â

Thereâs also the continued risk of long COVID, an array of persistent and sometimes disabling symptoms that can linger for months or years after infection, which is expected to be a public health threat for some time. The threat of long COVID is one reason health officials say itâs important to take reasonable steps to avoid infection.

Ferrer said 5% to 10% of people who have been infected with the coronavirus may end up needing long-term care, âand that will have implications for all of us.â

âWe worry a lot about long COVID, and we track all of the studies. Itâs very real for millions of people across this country who are debilitated by the symptoms that they continue to experience,â Ferrer said.

Times staff writer Howard Blume contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.