- Share via

In the hospital, La’Veyah Mosley struggled at first to understand what had happened. The 12-year-old girl woke up with both arms covered in layers of gauze.

“Do I have fingers?” she asked her mother, Staneisha Matthews.

The doctor eventually told her the hard news: On her left hand, no, she did not. Matthews reassured La’Veyah that she would recover, then slipped away to the hallway to cry.

La’Veyah is soft-spoken and shy — apt to sometimes keep her troubles inside. But in sports, she’s competitive, and in the months to come she would display remarkable strength. Even in her hospital bed, she remained optimistic and comforted her mother: “Mom, I’m OK.”

Just days earlier, La’Veyah had been playing outside in her family’s front yard in Broadway-Manchester with her two sisters, waving around a sparkler the morning after the Fourth of July holiday.

A neighborhood friend handed her another firework he had found in the street. He said it was a smoke bomb. Her twin sister, La’Niyah, needed to go the bathroom and begged her to wait to light it until she got back. La’Veyah stood impatiently while her younger sister, 8-year-old Jay’la, bounced with anticipation.

But La’Veyah couldn’t wait. She held the smoke bomb in her left hand and ignited it with the sparkler, expecting a burst of color.

The ensuing blast ripped the air with a blinding flash and a sharp crack.

Then absolute silence. La’Veyah lay crumpled on the ground, ears ringing. White smoke filled the air. Jay’la was lying in the dirt somewhere behind her.

La’Niyah stood frozen in the living room as the explosion shook the apartment. She ran over to La’Veyah and dragged her up the concrete steps and into the living room, screaming for their mother.

Matthews, 33, was in her room folding laundry. She ran out to find them huddled on the floor, blood pooling around them. So much blood was pouring out of La’Veyah that her mother couldn’t figure out where it was coming from, how this had happened. It felt like a horror movie.

Outside, Jay’la was screaming that she couldn’t hear. La’Veyah was shaking. Her hand felt as if it was on fire.

At the hospital, doctors surveyed the damage: La’Veyah had suffered corneal abrasions in both eyes, ruptured eardrums and fractures in her forearms and in the fingers of her right hand. Her wrist bones had been dislocated by the blast. Those would heal. But she lost all the fingers on her left hand, and her right hand was severely burned.

She learned the blast had not come from a smoke bomb butmost likely a powerful firecracker like an M-80, which are illegal but common in California.

Wounds like La’Veyah’s are more often inflicted in war zones. Yet fireworks such as M-80s and bottle rockets have, for decades, caused devastating injuries to unsuspecting residents.

In 2021, the Los Angeles Fire Department responded to 280 fireworks-related calls, with more than 100 people suffering injuries. Sparklers cause many of the burns, blazing at over 2,000 degrees. Fire Station 66 in South L.A., which responded to La’Veyah’s accident, is among those that receive the highest number of fireworks-related calls.

Such injuries have increased over the last several years, according to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Between 2006 and 2021, injuries went up by a quarter, according to the agency’s latest report.

Last year, about 11,500 people were injured by fireworks in the U.S., and nine people died. Children 15 and younger accounted for 29% of injuries. The body parts most often damaged are hands and fingers.

Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, where La’Veyah was treated, in July saw so many patients injured by fireworks that a whole floor was dedicated to treating them.

Dr. Jennifer Hsu, an orthopedic surgeon and chief of microvascular upper extremity and hand surgery, treated 19 patients for traumatic fireworks injuries over the July 4 holiday, the most she has seen in her nine years at the hospital. Sixteen were children, who in many cases did not understand what they had picked up.

“It’s so devastating to see these kids come in and see them go through multiple procedures to try and save as much of their hand as possible,” Hsu said. “Even after the physical wounds heal, for many of them the psychological wounds can carry on long after.”

La’Veyah spent 10 days in the hospital, where doctors worked to save her hands. What remained of her left thumb, wrist and palm left open the possibility of reconstructive surgery.

Her mom feared La’Veyah didn’t yet grasp the full consequences, the permanence of the missing fingers, and watched La’Veyah closely for signs of depression or sadness. Veyah, as she is known to friends and family, had dreamed of playing professional basketball when she grew up. Would her daughter, Matthews wondered, ever play any sport again?

And what about psychological trauma? With the burst of a firework, everyone who was there could be jolted back to the horror of that morning.

When La’Veyah returned from the hospital, Matthews hoped to keep her at home as she recovered from her injuries. But La’Veyah pleaded to at least sit in the bleachers to watch her youth football team practice.

She was back on TikTok 13 days after the accident, her arms in casts and slings, doing a dance with her twin.

She used the platform to update her friends on how her hands were healing, flexing the fingers on her scarred right hand for the camera, and even sharing a small still image of her left.

“She’s a different type of strong,” Matthews said. “It’s like she has a point to prove.”

::

On a cool August evening, 10 days before school would start, La’Veyah sat by herself on a bench overlooking the football field at the Watts Learning Center Middle School.

She recently had been out there warming up alongside her football teammates — one of four girls, including her sister, to make the team. Her days back then were busy: basketball practice every day after school, followed by football practice for another two hours, four times a week.

“It was hard,” she said quietly as she watched her twin sister run drills alongside the boys. “Sometimes I miss doing it.”

A teammate, Izabella, joined her on the bench. It had been a while since they had last seen each other. They went over first-day-of-school outfits before Izabella broached the topic of her injury.

“So you’re going to have a cast [at school]?” Izabella asked. La’Veyah nodded, holding up her right hand.

“I write with my three fingers,” she explained. “It’s easy. Like, I’ll hold a fork with my three fingers right here.” La’Veyah showed Izabella how her fingernails were already growing back. They didn’t speak about her left hand.

Marc Maye, the general manager of the youth football team, said La’Veyah asked to return to the team days after she left the hospital. The resilience she displayed after her injury was the same determination he’d seen her carry onto the football field, playing mostly against boys.

“She gets knocked down and she gets back up,” Maye said. “That’s how she’s able to compete and be around all those guys and not be afraid.”

But he couldn’t let her play. Not yet. He appointed her junior coach.

La’Veyah thought she still might be able to play basketball and wondered what a prosthetic hand would look like and how it would work. She imagined it shooting lasers.

At a fundraiser event at LAFD Station No. 64, La’Veyah spoke about what had happened, fighting her shyness.

She recounted the accident in front of cameras and a crowd of 40 who came out to raise money for her GoFundMe to pay her medical bills.

LAFD Assistant Chief Jaime Moore said her story was one they could all learn from.

“As tragic as La’Veyah’s injuries were, it could’ve been much worse,” Moore said. “La’Veyah should show all of us that there is an opportunity to change what’s happening in Los Angeles next year with fireworks.”

::

La’Veyah was having a difficult time at doctor appointments, where Dr. Hsu had to change her casts and examine her hands.

Those were the hardest days, La’Veyah said. She would steel herself for what was to come and tried her best to keep from crying, but even the painkillers helped little against the searing pain. Matthews gently cradled La’Veyah and they got through it together.

In August, Matthews told La’Veyah she could delay going back to school and do independent study. She worried what other kids would say to La’Veyah about her injuries or if she would overexert herself.

La’Veyah, was insistent: She wanted to be back in class.

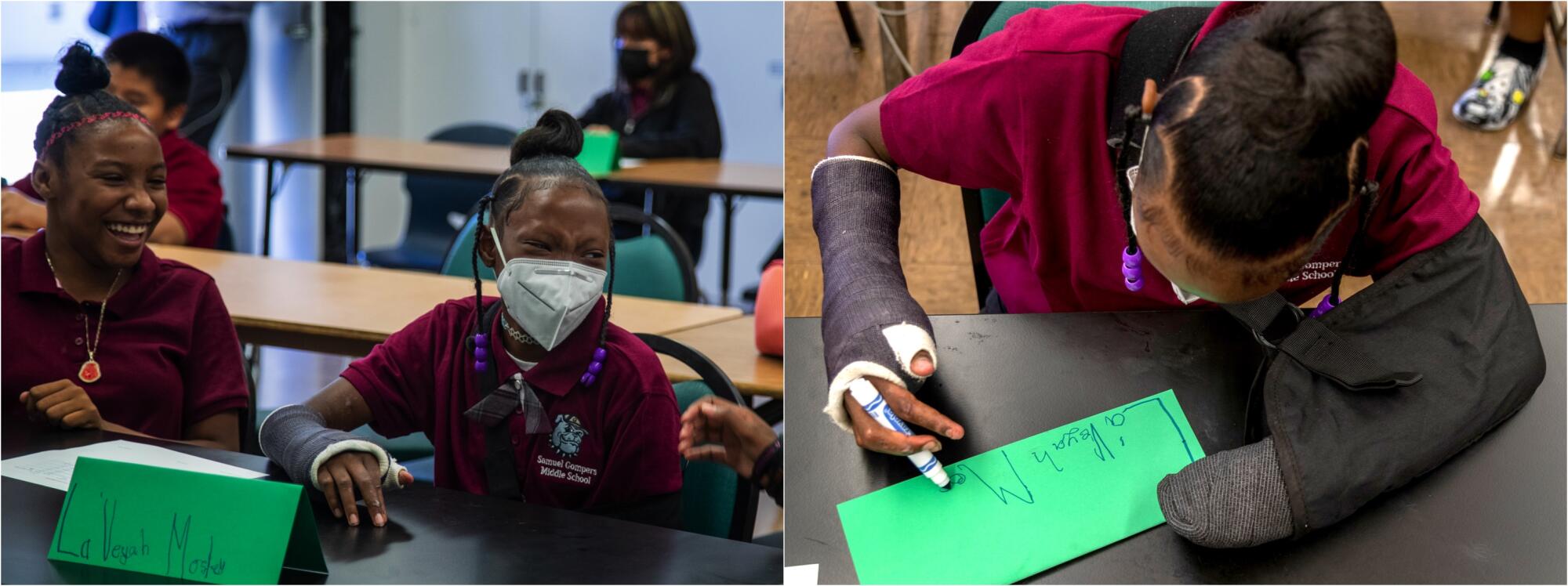

On the first day of school, her classmates avoided awkward questions about her injuries. At lunch, La’Veyah managed to open ketchup packets on her own with her teeth but needed La’Niyah’s help to soften and open her frozen kiwi strawberry slushy drink.

But in September, the twins began having trouble with boys at school. One of them called La’Veyah a “disabled b—,” Matthews said. They began taunting La’Niyah about her sister’s missing fingers. Twice, Matthews said, La’Veyah nearly got into physical fights with classmates who had mocked her. La’Niyah would quickly appear beside her, forcing the boys to reconsider.

When asked about the bullying, La’Veyah’s shoulders fell. “I don’t care,” she said softly. La’Niyah agreed.

But Matthews agonized over her daughters being picked on. She decided to take the girls out of Samuel Gompers Middle School and enroll them at Grace Hopper STEM Academy, a charter school in Inglewood with separate campuses for boys and girls.

Maybe there, she thought, they could find a way to move forward.

::

Before their arrival, Principal Yesmin Ortiz briefed the seventh-graders on the Mosley twins. Like them, other students had faced hardships, coming from broken homes and foster families.

If La’Veyah and La’Niyah want to share what happened, they would, Ortiz told the students. But she cautioned them not to press the girls.

By the time they arrived, most of the classmates already knew. La’Veyah’s story had already been covered by local news outlets. On Instagram, Matthews shared updates of the twins, capturing moments such as La’Niyah buttoning up her sister’s sweater and the family out on a long bike ride.

The girls became part of Grace Hopper’s 19-member seventh-grade class. With a 1-to-15 teacher to student ratio, La’Veyah would get individualized help to keep her on track, even when she missed class because of doctor appointments.

At Grace Hopper, the sisters joined their classmates on a trip to the La Brea Tar Pits, where they gawked at the mammoth fossils. Just before school let out for winter break, they joined their classmates at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

They walked around the displays, peering at bugs under microscopes. La’Veyah paused at an upright life-size polar bear display, touching its left paw gently with her right hand.

Matthews was greatly relieved at how they were integrating into the new school, joining the basketball, chess and fitness clubs.

“Nobody here is mean,” La’Niyah reflected. In basketball, her sister had already relearned how to play. Without the casts, La’Veyah steadies the ball with her left hand and shoots with her right.

Thanhdi Nguyen, the health teacher and fitness instructor at the school, saw the girls slowly come out of their shells. For a while, La’Veyah would lean on her sister to answer for her. But when it came to competitions in the fitness club,such as relay races or games, the twins lighted up.

“They keep each other up to speed,” Nguyen said. “Any time I put on some type of competition, they’re ready for it.”

Matthews fears the fireworks on New Year’s Eve will be too much to bear and plans to take the girls out of town. But otherwise, the family was ready to move forward. Already, the girls were preparing for the spring semester at Grace Hopper.

On a recent evening, Matthews took the family to an ice rink at L.A. Live. After the year they had had as a family, she wanted them to experience something joyful. La’Veyah took to the ice and, once more, barreled ahead.

“OK, Veyah! OK, girl!” Matthews cheered as her daughter, wearing a black beanie, shot away on her skates. “I can’t follow you that fast!”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.