âYou donât want to live anymore.â Californiaâs seniors living in poverty struggle without retirement savings

At 61, Linda Fett arrived at the Union Rescue Mission on skid row this year without any savings. After her divorce in 1992, the long-term caregiver used what little money she had to pay bills, including car payments and other expenses, in order to live independently.

Fett now receives about $220 a month from the countyâs general relief program, with $150 going into the Union Rescue Missionâs Gateway Project, which provides short-term housing for those on the verge of homelessness. That leaves her about $70 a month to pay for basic necessities.

âThe biggest hurdle I kept coming across while being a caregiver was that rents were high, even back East,â she said. âI kept driving around to find affordable housing ⌠I didnât really have much of a savings. I lived on my paycheck.â

Fett is part of a growing population of seniors living in poverty without retirement savings or a pension and is having to eke out an existence by working past retirement age or scraping to get by on state or federal assistance. She doesnât have family members she can reach out to for help.

Adults 65 and older are the only age group in the country that saw an uptick in the poverty rate last year, from 9.5% in 2020 to 10.7% in 2021, according to the U.S. Census Bureauâs Supplemental Poverty Measure, which factors in programs aimed at helping low-income families and individuals who are not included in the official poverty rate.

More than 7 million Californians have had no access to a workplace retirement program. Can the CalSavers program help?

In Los Angeles County, about 14,896 adults 55 and older experienced homelessness in 2020, according to numbers provided by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Homelessness among older adults in the county has gone up by 20% since 2017.

The over-60 population in California is growing faster than any other age group and is projected to comprise 10.8 million people by 2030, making up one-fourth of the stateâs population. To address the anticipated population boom, Gov. Gavin Newsom released the Master Plan for Aging in 2021, outlining five goals to be accomplished over 10 years to help better the health and lives of the elderly and people with disabilities.

Among the chief concerns is finding ways to provide more affordable housing options for seniors, who become homeless mainly because of unemployment, disabling health conditions, evictions and weak social circles, in which older adults donât have friends or family members to help them out, according to the agency.

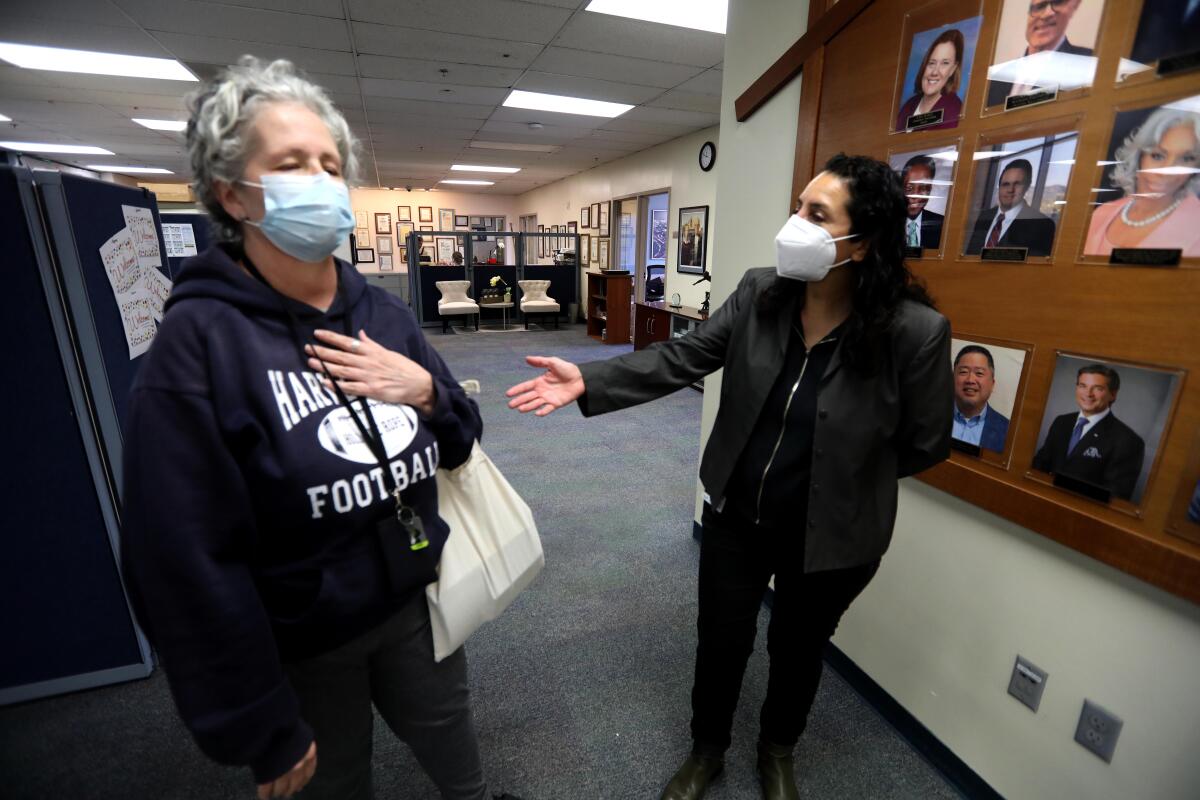

Donna Benton, professor of gerontology at USC and a member of the Californiaâs Master Plan for Aging Stakeholder Advisory Committee, said older adults face a unique set of challenges when they become homeless, because they often have to compete with other high-priority groups in the system, such as those suffering from mental health issues or who have recently come out of incarceration.

Older women of color are especially susceptible to housing insecurity, because they tend to be caregivers for their spouses or other family members, Benton said. These women often leave their jobs, move in with a relative and care for them without having to pay for rent or earn any income, she said. But once the relative dies, itâs difficult for these women to find new housing or to get back into the job market because of their age.

âIt may be the first time, because of their caregiving circumstances, that they lose their housing,â Benton said. âThey may be struggling because they donât understand the new system of care that they have to try to navigate and they may not have access to the internet or family members and they may not know where to turn to services that are there to help them.â

Lack of housing also exacerbates health conditions and shortens the lifespan for older adults, Benton said. She said while there are programs such as the Program of All Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which provides medical and social services to the elderly, theyâre limited by geographic location and other factors.

âSometimes, people have enough where they donât qualify for medical [needs] and they have to skim down to poverty and thatâs emotionally difficult for them,â she said. âPeople are more likely to become depressed and anxious related to the lack of support that they can have around these long-term care services.â

Republicans keep coming up with ways to destroy Social Security. Donât let it happen.

Denny Chan, managing director of Equity Advocacy for Justice in Aging, said generational poverty has a compounding effect and often falls along racial and gender lines in part because of fewer opportunities to participate in the workforce, because of discrimination or other factors.

âFor those of us who have had the privilege and are afforded the opportunity to retire, your Social Security check is going to look different than other peopleâs because of the ways in which workplace discrimination impacted your earnings and how much you paid into the system,â Chan said.

Californiaâs competitive real estate market and shortage of housing stock also makes it difficult for older adults, who have fixed incomes from Social Security and other sources, to rent or purchase homes, Chan said.

Some senior programs, such as home-delivered meals and in-home supportive services, usually rely on the fact that participants are housed, according to Chan.

âThe support system we crafted for older adults largely presumes that there is a steady and stable place to call home, and one of the things we fight for regularly is ensuring that the people who donât want and donât have to go into nursing facilities can stay in the community,â he said. âUnfortunately, the system assumes there is housing security to begin with.â

Fett, who has been relying on food stamps, is planning on filing for Social Security next month. Union Rescue Mission is planning to move her to the groupâs Hope Gardens Family Center, a housing facility for women and children in Sylmar, sometime next year.

âPeople are living longer but they also have disabilities and have things happen when we age,â Fett said. âThere needs to be assisted living. Iâve worked with clients as a caregiver whoâve gone without help and it broke my heart to walk into their apartments.â

After Roberta Gordon, 80, was evicted in February from a senior housing complex in Corona, her son used a credit card to pay for a room for her at a Motel 6 for a week. Because she isnât able to live with her son, she moved across the street to Hotel del Sol to a room being paid for by City Net, a homeless nonprofit.

Gordon has been trying to find someplace else to live ever since but a lot of apartments are not suitable for her because sheâs disabled. And those who she did contact said they had nothing available and offered to put her on a two- to three-year waiting list.

Gordon is enrolled in the countyâs Section 8 housing program, but the agency provides vouchers of only up to $1,400 a month for rent. When landlords found out that she was in the welfare program, they would often tell her they werenât accepting Section 8 funding at this time. Her vouchers ran out Oct. 12.

âIf I didnât have this hotel room, I would have to live in my car,â she said. âCity Net is paying this room for more than $100 a night. I canât pay for it.â

Gordon said City Net is trying to see if they can get her a spot at the former Ayres Lodge and Suites Corona West, off the 91 Freeway, which is being converted into supportive housing for the homeless. But there are only 52 units available, and itâs not expected to open until February. Until then, Gordon spends about four or five hours a day calling apartment listings â an endeavor she called a âwaste of time.â

âWhat place can I find?â she said. âEven if I found something in someoneâs house for $800 a month, if I spend $800 a month, then I wouldnât have money for food or gas or anything else.â

âItâs very hard,â she said. âYou just donât want to live anymore. There used to be a time when families would take in family members and theyâd own a house for three generations. They just donât take in family members anymore â theyâre on their own.â

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.