‘There’s our family name’: Sacred book honors Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII

- Share via

The book weighs 25 pounds and is more than 1,000 pages long. It is roughly the size of the Gutenberg Bible.

Instead of the word of God, it contains names — 125,284 names.

A few are living. Most are dead. All were incarcerated behind barbed wire during World War II, their only crime their Japanese ancestry.

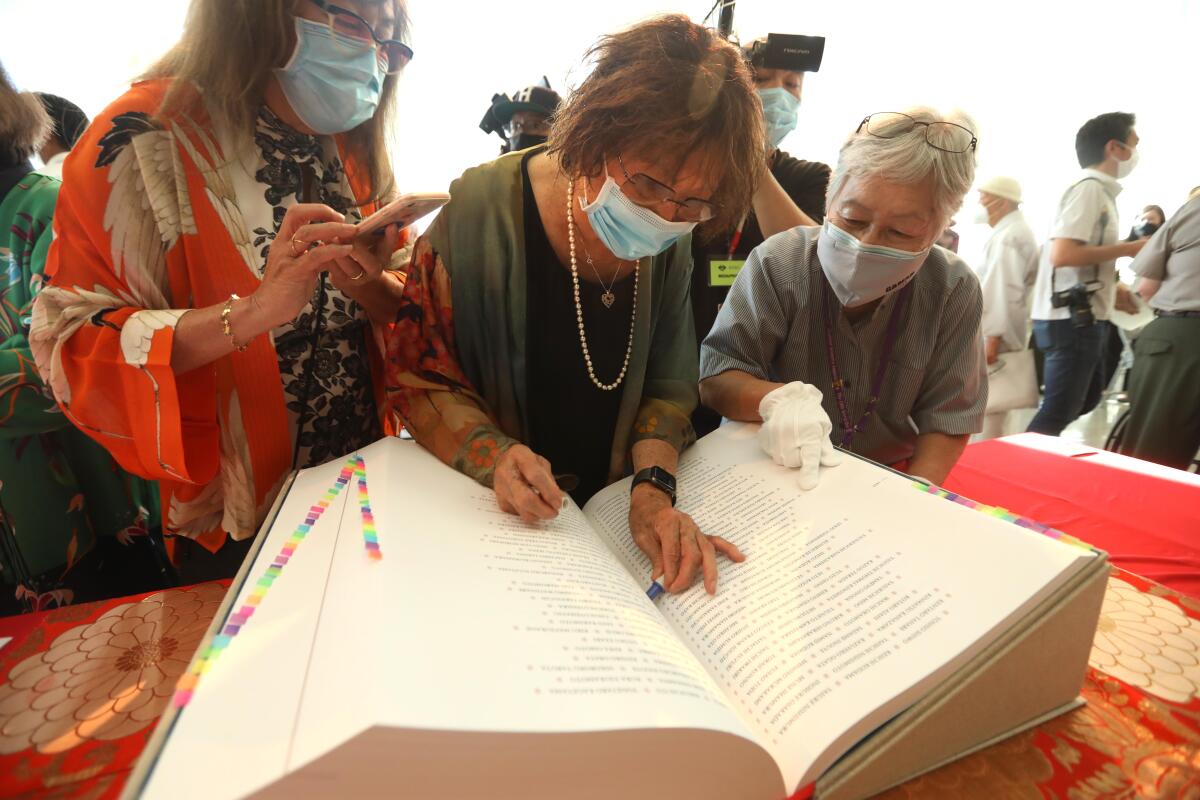

June Aochi Berk stepped forward. Her name was in the thick tome.

Next to the names of her parents, Chujiro Aochi and Kei Aochi, she stamped a blue circle.

In the next year, survivors and their descendants will make a pilgrimage to the Japanese American National Museum in Little Tokyo to do the same for the names of their loved ones.

All 125,284 names have never been collected in one place. With 75 incarceration sites — some, like Manzanar and Heart Mountain, well-known, others forgotten — records are scattered.

The book, called the Ireichō, which means “record of consoling ancestors” in Japanese, is a tribute to the immeasurable loss each and every one of them experienced, even if they were children at the time. It highlights their dignity as individuals, with lives they left behind when the U.S. government reduced them to faceless enemies.

The blue circles represent the Japanese tradition of leaving stones at memorial sites.

“This is not just an act of remembrance, but an act of repair,” said the Rev. Duncan Ryuken Williams, director of the USC Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture and founder of the Irei project, which includes the book. “Japanese Americans have always been seen as un-American or anti-American — a mass of people deemed a threat to national security, more than other Asian groups in the history of Asian America.”

Berk, 89, was among the survivors who stamped the Ireichō on Saturday as museum officials unveiled the book to visitors.

She was 10 when strangers herded her into a horse stable at the Santa Anita racetrack, then to the Rohwer concentration camp in Arkansas.

Her father, a gardener, and her mother, who took in mending and washing, lost everything.

She was allowed to stamp only two names. She chose her parents and left her own name blank. Her three siblings’ names are also in the book.

“They were so stoic. They donned their Sunday best to leave. They never complained, never cried,” Berk, of Studio City, said of her parents. “They simply started over after the U.S. blamed us for a war we did not cause.”

The afternoon started with an Indigenous blessing from a man representing the Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming.

Survivors, descendants and clergy — nearly 150 in all — stepped through the ceremonial arches at the Nishi Hongwanji Buddhist Temple and solemnly entered the museum as taiko drummers pounded. Some dabbed at tears.

Inside the museum’s great hall, monks intoned prayers as tearful people bowed respectfully in front of the book.

“The public’s interaction with the Ireichō will be the first step to correct the historical record and ensure that it is accurate for future generations,” said Ann Burroughs, the museum’s president and chief executive.

The Irei project, funded by the Mellon Foundation, includes a website where people can search for names, as well as a future light installation projecting all the names.

Compiling the names took several years of exhaustive research, including combing through the 1940 census and reviewing World War II draft cards, Williams said.

The complexities of Japanese names and anglicized names, as well as women who took their husband’s names, presented more challenges.

“Different groups have put out different numbers. But nobody’s known an accurate number,” he said of the total number of incarcerated people of Japanese descent.

Actor George Takei was listed as Hosato George Takei at the Rohwer camp, then Hozato George Takei when his family moved to Tule Lake in Northern California.

“Since I know him, I just called him up and he said he’s always spelled it with an S,” Williams said.

Takei also told Williams: “Everyone kind of knows me as George Takei — just put me as George Hosato Takei.”

For Hiroshi Shimizu, 79, who was born in the Topaz camp in Utah in 1943, his first four and half years were lived behind fences and barbed wire.

After his family moved to the Crystal City camp in Texas, his father worked as a spokesman for the incarcerated people, handling communications with the administration and helping families with paperwork.

“To go from that dark history to a place where we can see our names recognized in hopes this will never happen again is quite something,” Shimizu said.

On Saturday, Nannette Fujimoto Okada, 85, took her turn at the Ireichō, looking for the names of her parents, Mikio and Dorothy Fujimoto.

Okada, who arrived at the Amache camp in Colorado when she was 4 years old, described the procession and name stamping as a “healing experience” and the “finishing of a journey.”

“It’s an ending,” she said, “that we need to close this chapter.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.