Think of L.A. spring as the pause between California catastrophes — with poppies

- Share via

Winters are easy. Winters, we can look across the vast eastward miles, and regard with pity the icebound, housebound millions in the manacles of winter.

So too their summers: sweaty, fleeting weeks of melting Popsicles, malodorous with bug repellent, the calendar countdown to hurricane season.

Autumns: a season of Facebook posts of leaves tinted by xanthophylls, carotenoids and anthocyanins. You can get nature’s same color impact by looking at egg yolks, flamingos and blueberries. Leaves end their lives sodden underfoot, or raked into picturesque bonfire heaps that fill the fall breezes with fragrant waftings of CO2 and photochemically reactive substances.

But spring? Our spring had always arrived on tiptoe and sat in the back row, the opposite of the ebullient temperate-zone season.

So Angelenos can be absolved of spring envy. Our Mediterranean-climate constancy doesn’t deliver the liberating, pagan exuberance of spring, like prison parole with greenery: Stravinsky music and maypoles, purple crocuses muscling their way through crusts of ice, hibernated human millions doffing their woolies the way snakes shed their skins, to clad themselves anew in sunlight and mid-weight cottons.

Here, we have to work for spring. We have to look, and look again. From our feet up, things feel pretty stable almost all the year; seismographs show wild zigs and zags, but in Southern California, temperatures live demurely within standard limits.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Daniel L. Swain is a climate scientist at UCLA and a California climate fellow at the Nature Conservancy; you’ve met him here before. “Spring was kind of a reprieve. It’s as if climate and weather and natural hazards can take a breather,” Swain explains. “You do have fires, but not as bad as in summer and autumn. You can see floods, but usually not as bad, and heat waves, not as bad as summer and autumn.”

On our calendar of hazards, spring stands alone for the skimpiness of its drama. “There’s really no other season that checks all those boxes. Autumn isn’t flood season, but it sure is fire season. Summer sure is fire season if not necessarily peak fire season. For a place famous for relatively benign weather most of the time, California really is subject to a lot of significant extremes not obvious at the outset.”

What, then, to look for in an L.A. spring?

Its inaugural month, March, can have lamb-and-lion fitfulness, sizzle to drizzle and back again.

May gray is the overture to June gloom, a damp cloudiness without actual cold (and often without actual rain). “We don’t get that in the fall,” Swain points out. “That’s one way spring is not symmetric with the transition to fall.”

But — with climate, it’s always about “buts” — don’t set that in stone. It’s all changing, warming. “We’re seeing summerlike temperatures bleeding into non-summer months; the second half of spring increasingly gets summerlike temperatures. In California that means ‘drier.’ ”

It could even mean years of only two seasons — years, as Swain says, when the most notable difference in the Southern California year is “between summer and not summer, between the time of year when it sometimes rains and the time of year it essentially never rains.”

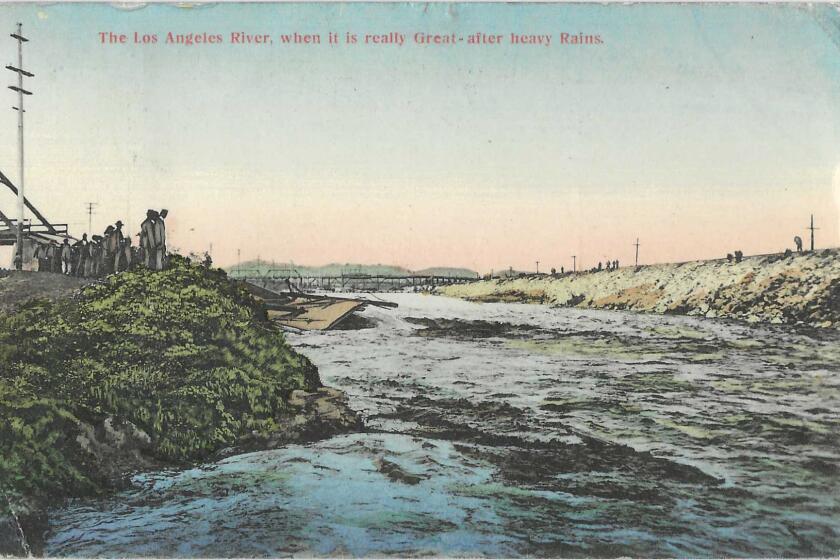

We could even see a recurrence of the awesome — in the classic sense, not the current correct-change-at-Starbucks sense — California floods of yore. The great West Coast floods of 1862 sent down rains in Old Testament volumes, melted the snowpack and turned much of California into an inland sea, submerging towns, ranches, roads, people. Our three principal rivers — Los Angeles, San Gabriel, Santa Ana — overflowed and merged into an ocean, miles upon miles of water. The L.A. flood of 1938 tore out bridges and isolated the San Fernando Valley from the rest of the city.

After one too many floods, L.A. turned its river into a concrete channel. Today and in the future, the river could be part of the answer to some of the city’s problems.

In this future springtime, monster floods could reappear. “Southern California is likely on average to be a drier place than it used to be, yet punctuated periodically by really, really intense storms with very large floods,” cautions Swain. “We will have some decades where we remember the big floods more than the big fires. It’s kind of like a big earthquake on the San Andreas fault — no one has a recent memory of it because it hasn’t happened in a long time, but it’s inevitable.”

Now, to the spring flora, and the flowers we have versus the ones we may wish we had.

The effusion of bulb flowers of the East and Midwest — the daffodils, hyacinth, freesia, tulips — need a cold hibernation to generate the scented show they put on. They don’t get it here.

Like us, some plants can adapt to L.A. These spring beauties do not. There were years when I tried to buck nature; I planted lily of the valley pips in L.A. soil, and to will them to grow and bloom, I carried blenders full of crushed ice to pack upon the earth, to try to fool the flowers into believing they were thousands of miles farther and 50 degrees colder than they were. The only thing it accomplished was probably to convince the neighbors that I was a lush who started my mornings with a blender of frozen margaritas.

You can determine L.A.’s seasons by our plant life. For example, right now, it’s jacaranda-blooms-stuck-to-your-windshield season. And to understand the Southern California landscape you see, you have to realize that, like you, it is probably not from around here.

We’d be churlish to complain. Blossoming tendrils of flowering jasmine put out enough scent to overpower, for a moment, the stink of gas leaf blowers. We have what is supposed to be the largest camellia collection in North America, thriving in the cool microclimate at Descanso Gardens, extraordinary varieties first cultivated before World War II on his own acres by “the Camellia King,” horticulturist Francis Miyosaku Uyematsu.

There’s a California lilac — not the true syringa lilac of rhapsodic song and poetry but a ceanothus. We still have our California lupine and poppies, owl’s clover and tidy tips, but where once they bloomed, as Frank McDonough has read, from the Altadena plain to San Pedro, now there are the merest patches, except in the high deserts, where a rainy superbloom season — this won’t be one — births blues and oranges so wide and intense that you still see them shimmering even after you close your eyes.

Botanist McDonough has spent a quarter-century as the botanical information consultant at the Los Angeles County Arboretum. So many things have confined our spring floral outburst, he says — humans’ relentless spread, the caprices of rainfall, and chiefly, the temperatures: “I looked at the increase in temperatures from the 1870s to now, and you can see a seven-degree increase in the lowest temperatures, and a four-degree increase in the highest temperatures, the daily minimum and maximum. That’s got to have some effect.”

Still, we can console ourselves with immigrant flowers that Angelenos have welcomed to their gardens, like agapanthus and acacia, cascades of wild jasmine, and, at the Arboretum, yellow irises that are regarded elsewhere as a weed, says McDonough, an “aggressive woodland bully.” (Which makes me imagine a swaggering tough threatening the other flowers with “This is my topsoil now, see? So scram, if ya know what’s good for ya.”)

At the Arboretum, “we do get calls: ‘Are your cherry blossoms flowering yet’? They’re mistaking pink trumpet trees for cherry trees. They put on a show; they start blooming as early as late February, all through March and April, and may even go into June. We have a lot of those. Our only cherry tree is [one] pink cloud flowering cherry.”

And at the top of the spring-flowering food chain stands our charismatic megaflora, the ultraviolet jacaranda, which can still bloom and drop its sticky petals late into May and sometimes June, as you know if you have to park your car beneath one. Ah, the breathtaking Jacaranda mimosifolia — the carwash’s friend. And even as you step carefully around the jacaranda’s purple petal slick, keep telling yourself, “There’s no place like L.A., there’s no place like L.A.”

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.