The lines, the signs, the fights: In 1970s L.A., gas came at a premium

Which three-word phrase should always be spoken cautiously?

- I love you.

- Just do it.

- Fill âer up.

All of them, actually, but that last one â depending on your choice of ride, a full tank of gas can now cost you within fumes-sniffing distance of a hundred bucks.

How did it come to this â again?

The internal combustion engine has had no more ardent a devotee than Southern California. The romance got off to a slow start 125 years ago, when the first experimental gas-powered automobile rolled onto Broadway downtown at about 2 a.m. on Sunday, May 30, 1897, avoiding the equine morning rush hour. The carâs creator, J. Philip Erie, is said to have spent $30,000 to develop the one-off â a stupendous equivalent to about a million bucks today.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Seven years later, by one count, there were 1,600 motor vehicles on the cityâs roadways, limited by law to 6 mph in business districts â as if anyone could drive even half that fast in downtown L.A. by 1915, when all of the countyâs more than 55,000 horseless carriages seemed to swarm into the center of town at once.

Soon enough, the spreading city would design itself around its cars. Gilmore â the family that pioneered the Farmers Market and Gilmore Field â sold gasoline named Red Lion, Blu-Green. Violet Ray gas was actually tinged with violet.

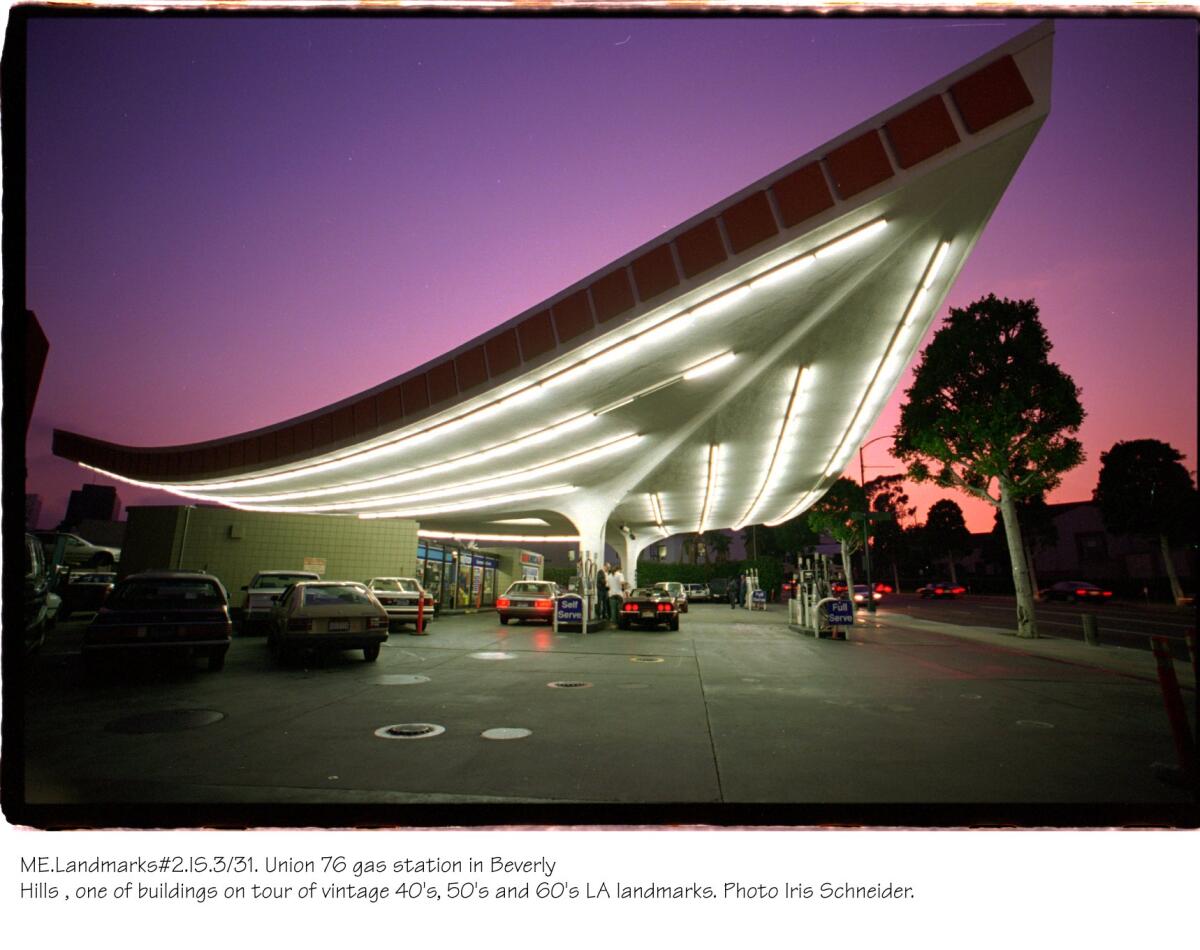

A few filling stations are of fantastical design. The midcentury modern Googie-style Union 76 station in Beverly Hills was designed by Gin D. Wong, a lead architect with the team of Pereira & Luckman that helped to create the still-futuristic-looking theme building at LAX, along with others, among them renowned Black architect Paul Willliams.

Wongâs gas station design was intended for LAX, too, but was eventually built in Beverly Hills, where its glamorous swoops and arcs have found their way, of course, into movies and TV shows.

The first gas pumps really did require pumping, not unlike a water pump, and it took some skill to operate them safely. So spiffily uniformed attendants â âgas pump jockeysâ â who washed windshields and checked tire and oil pressure were summoned to the pumps by a double-ding bell set off when cars rolled over a snaky wire laid across the pump-island lanes.

All, all but gone now, like free glasses or steak knives with a fill-up, free maps, free air for your tires, free water for your radiator, free maps for your voyage.

As soon as pump technology permitted, the first independent self-service gas station in L.A., and perhaps the country, opened in East L.A., in May 1947. Pump jockeys were replaced by âgirlsâ who skimmed from dispenser to dispenser on roller skates, making nice and making change.

Within a year, the city ruled that self-service was a safety hazard. Other cities and states outlawed self-service gas, with the encouragement of major oil company chains and the American Petroleum Institute, which called self-serve âa menaceâ to safety.

It wasnât until the oil embargo gas shortages of the 1970s that self-service became the norm â and the necessity. It required a learning curve; people drove off without their gas caps and pumped gas onto their shoes and even into their radiators.

Nostalgia-driven sites like to post photos of filling stations from days of yore selling gas for 29, 39, 79 cents a gallon, but donât be fooled. Prices now are at real-dollar records, but inflation-tweaked into modern dollars, that long-ago bargain gas works out to two, three, even four dollars a gallon.

In the late 1970s, the nation was shocked when prices broke the three-digit barrier into a buck a gallon. Thatâs one reason gas stations wound up using electronic price signs; things changed too fast for the fellows who used to climb up and down ladders to switch them by hand.

For more than 25 years, Californians have paid at the pump rather than paying at the doctorâs office. The California Energy Commission estimates that the stateâs âspecial recipeâ cleaner-burning gasoline has added something between five and eight cents to the cost of a gallon of gas. And the stateâs singular vapor-recovery nozzles (which an automobile website refers to as, adult-alert here, foreskins) keep gas fumes from flowing out into the atmosphere, another blow for cleaner air. Deal with it.

Gas prices are high across California, and itâs unclear when prices will go down. But, there are ways to save money on gas. Here are some tips.

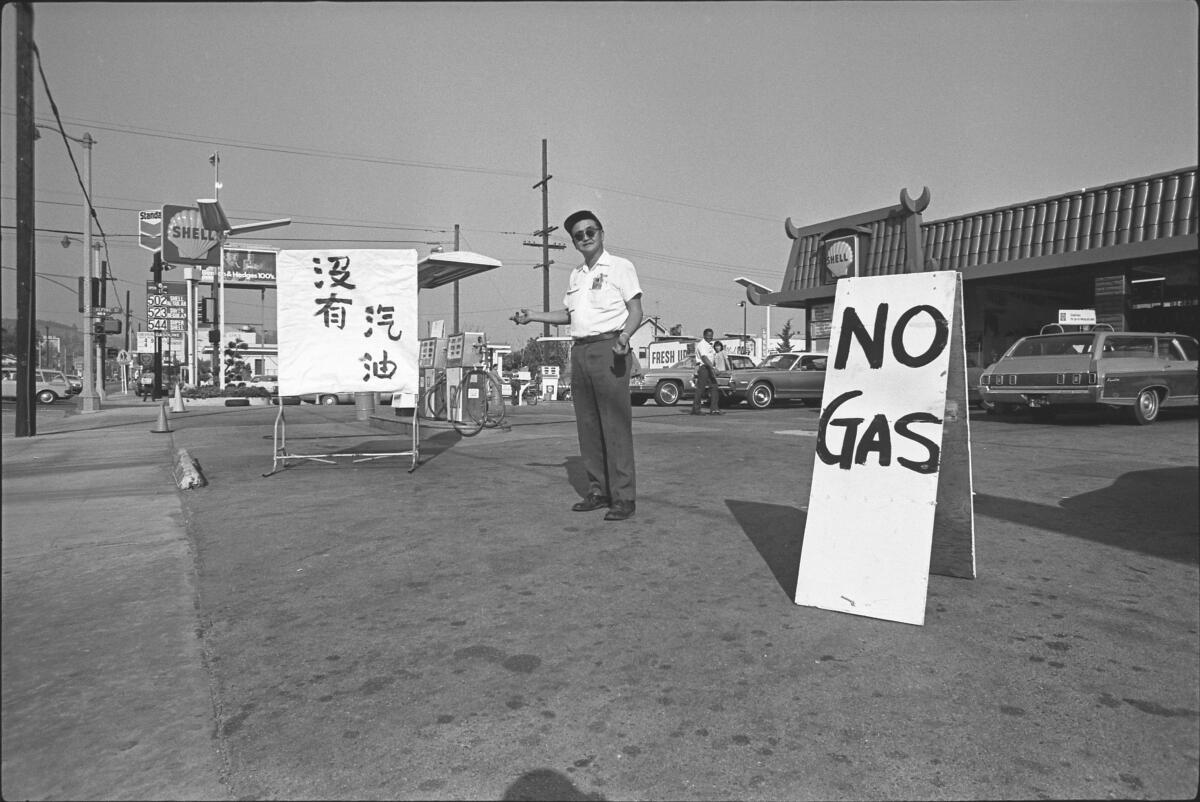

Yet throughout two devastating crises in the 1970s, price was secondary. The real angst was over whether you could find gas at all. After the 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and a coalition of Arab states, Arab members of OPEC embargoed oil sales to the U.S. and other nations that had taken Israelâs side.

Again, in 1979, after the Iranian revolution, oil supplies fell â fractionally, perhaps by 4% or 5%. But the combination of prices going up and quantities going down provided the nation with a wild and panicky exercise in supply, demand and human psychology.

Weâd rationed gas during World War II, usually to less than four gallons a week for a passenger car. In 1942, California capped speed limits at 35 mph. In L.A., unpatriotic speeders were warned theyâd be stopped, and â worse than a fine â their names would be reported to the local rationing board, so if they found they needed new tires one day, or more gas than their rations allowed, they would be up crap creek.

At least twice in the crises of the 1970s, oil shortages were so severe that California, under Govs. Ronald Reagan and Jerry Brown, instituted an even-odd system for buying gas. Under this system, you could not buy gas any time you liked. If your license plate ended in an even number, you could buy gas on even-numbered calendar days; odd-numbered plates got to buy on odd days. Personalized plates counted as odd.

The gas supply in 1974 was reported to have bottomed out at only about 20% below normal, but drivers acted about 50% below rational. Think of COVID and toilet paper hoarding.

Some gas stations kept briefer hours than banks. People parked outside service stations at night and slept there waiting for them to open. Lines wrapped twice around the block. One queue in San Pedro was 150 cars long.

The nearly 8,000 gas stations across California were told to fly a red, yellow or green flag â green when gas was available; yellow, gas for emergency vehicles only; red when the stations were empty. When the gas ran out and stations shut down, people made weather puns: Well, another dry weekend in L.A.

People were told to not buy gas unless they needed at least half a tank. Gov. Reagan singled out for nameless shaming a man who topped up his tank for 67 centsâ worth and then insisted on paying by credit card.

Youâve seen the signs advertising $6.95, $6.99 or even $7.05 for a gallon of regular unleaded. But whoâs buying it, and why?

Of course, fights broke out. Gas station attendants got clobbered with baseball bats and beer bottles. A man who reached the pumps after hours in line and found he could buy only $2 worth chased the attendant into the bathroom with a hammer. In Venice, at a self-serve station, people started beating up the empty gas pumps. One man jumped the long line of cars at a Hollywood station, and when angry drivers swarmed him, he held a gun on them with one hand and filled up his tank with the other. He was still filling it when the cops showed up.

In 1974, a customer at Sid Hackelâs gas station in Beverly Hills was told he could buy only $10 worth. So he spit on the attendant. Said Sid himself, âIf heâd done that to me, heâd be going around without any teeth.â

Of course, people cheated. They walked up to drivers waiting in line and fanned $20s and $100s to try to buy their way to the front of the queue. In 1979, a man who wanted to buy gas when his own license plate didnât allow him to switched plates from his wifeâs Dodge to his Cadillac. He got busted and was fined $20 â slightly more than 20 gallonsâ worth.

By the second gas-crisis go-round, in 1979, entrepreneurs were organizing surrogate gas sitters. Outfits like the Jockey Club charged to do the waiting for you: $150 a month for the first month of service, $50 a month thereafter, gas not included.

Gas theft was flagrant. This was before locking gas caps and flaps, and midnight rustlers put siphons to furtive use. In Santa Ana, someone hijacked a Shell oil tanker truck at gunpoint. An unknown thief drove an unmarked tanker up to a Hawthorne gas station and sucked up a thousand gallons from the underground tanks.

And of course, panic made people incautious. Members of a Santa Ana family were critically burned when gas they had stored in plastic bins caught fire. A Torrance driver whose gas gauge was broken tried to look into his tank to figure out how much he had and lighted a match to see better. Boom.

NASCAR cut the length of its races. The nation cut its speed limit to 55 mph, where it stayed for two decades. Unsold Cadillacs were stuck on lots as surely as saber-toothed tigers were stuck in the La Brea Tar Pits. Mileage-miserly Japanese cars got a firm foothold in the American market.

After each of these crises, we swear weâll never get suckered like that again, and then we backslide into our old habits and relearn that other, not inapt meaning of âgasâ â the cause of a gut-wrenching pain.

L.A. is a place like no other. Youâve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.