New child tax credit may be life changing for the poorest families. But will they sign up?

For Gloria Acosta, a mother of four, a $1,000 check each month would be life changing.

Sheâs been jobless for a few years. Her husband, a day laborer, has had little work during the pandemic. His earnings are barely enough to cover rent in the San Fernando Gardens housing project in Pacoima.

An extra grand would help pay for food as well as gas to take the children to school. Acosta would be able to buy them new clothes and school supplies.

Sheâs entitled to that much under an expanded federal child tax credit, which provides $300 a month for each child younger than 6 and $250 for an older child.

Itâs a program meant to fight child poverty during a tumultuous pandemic that brought job loss, illness and grief, and disproportionately affected Black and Latino people.

Parents who previously had not received child tax credits because of their immigration status or because they did not earn enough to file with the Internal Revenue Service and get the payments automatically are now eligible for the full benefit.

The first payments from the expanded federal child tax credit are being deposited in familiesâ bank accounts this week. Hereâs what to expect.

Yet they have proved to be hard to reach. Signing up for the program can be a complicated process, hampered by a lack of information in Spanish and other languages. Some of those now eligible mistrust the government and fear the aid is too good to be true.

The best approach, many policy experts and nonprofit leaders say, is to deploy trusted local organizers to spread the word in low-income communities.

Itâs a labor-intensive strategy that might mean taking computer tablets to homeless shelters, food banks, schools and pediatriciansâ offices to help people navigate the online application, said Elisa Minoff, an analyst at the Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Itâs difficult to say how many of the 73 million children in the U.S. have parents who arenât enrolled and could miss out on the monthly payments that started in July as part of a large COVID-19 relief package passed by Congress. The number could be between about 2.3 million and 10 million, experts say.

For the record:

9:57 a.m. Oct. 8, 2021An earlier version of this article reported that more than 10 million children could miss out on the new child tax credit. Experts estimate the number is between about 2.3 million and 10 million.

The program expires in December, but advocates are hoping that signing up the neediest families will justify an extension.

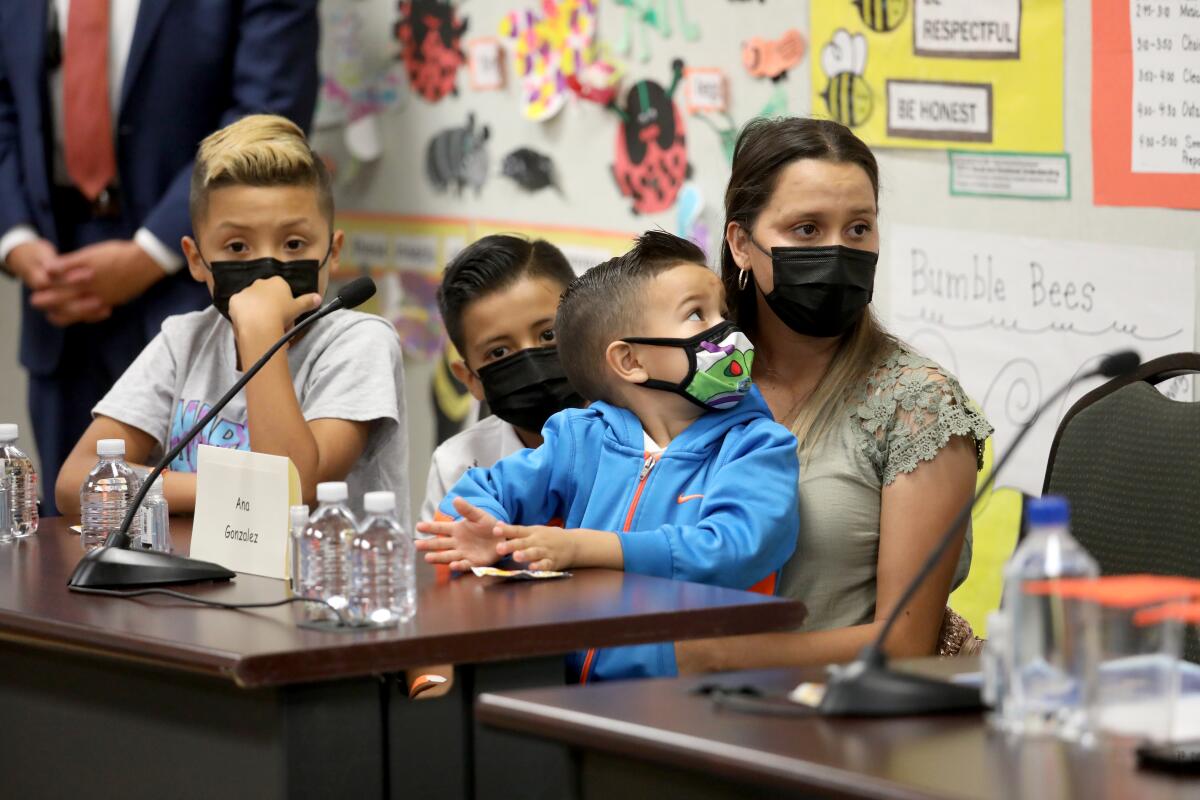

âThis is Social Security for children, and in order to lengthen its life, we need to show it really is working,â House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) said during a news conference in El Sereno in July. âOutreach, outreach, outreach is so important.â

Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Los Angeles), whose district includes El Sereno, said his office has sent out mailers to 40,000 households, along with text messages and Facebook ads.

Congress allocated $379 million to implement the new child tax credit, including outreach efforts to low-income people not already in the IRS system.

The IRS held sign-up events over the summer, spokesperson Raphael Tulino said, but in-person outreach dwindled amid the latest coronavirus case surge.

Since then, Tulino said, the IRS has been co-hosting virtual information sessions in Spanish and English with organizations that assist underserved communities.

But no outreach money is earmarked for those organizations, which are already operating on a shoestring.

âWe knew that as soon as the bill passed ... that Latino families in Los Angeles were going to miss out on it because theyâre very low-income or donât file taxes,â said Vanessa Aramayo, director of the Alliance for a Better Community. âItâs unfortunate that public resources are not made available to pair with this effort.â

In L.A. County, the families of 1.1 million children are eligible for the payments, which begin phasing out for couples who make $150,000 a year and for single parents at $112,500.

According to officials, at least 127,000 children in the county would be lifted out of poverty if their parents receive the payments.

Community organizers are trying to reach all needy families, but in the L.A. area they have particularly focused on Latinos, who along with Black children have the highest poverty rates statewide.

In L.A. County, several majority Latino congressional districts have high concentrations of children who would benefit, according to a report by the office of Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.). Those districts include communities such as Bell, Maywood, Compton, Boyle Heights, Koreatown and Westlake.

Families who were getting the previous child tax credit are seeing increases of at least $1,000 a year for each child. For those who were not receiving payments before, the gain is $3,000 to $3,600 a year per child, depending on age.

Caroline Danielson, policy director for the Public Policy Institute of California, said child poverty rates in the state could drop from about 19% to under 13%, assuming everyone who is eligible signs up.

âThe idea of getting $250 a month to help offset the cost of child care or food or transportation or whatever you need it for â itâs going to be transformative,â said Amy Everitt, president of Golden State Opportunity, an organization that specializes in outreach for tax credits.

But some of the low-income parents who would benefit most do not trust government programs, fearing they will be asked to pay the money back.

âOur communities have the mindset of, âWe have to work hard to earn our money,ââ said Yessica de LeĂłn, a case manager with El Centro de Ayuda, an organization with expertise in tax preparation that is helping people navigate the tax credit process. âNext year, when they see they donât have to pay it back, thatâs when I think itâs going to sink in.â

Luz Puebla, a mother of four children from South Gate, has fallen into debt after using credit cards to pay her bills during the pandemic.

Her husband, a repairman for a property management company, had his hours cut, and she has been staying home to care for the children.

Since her husband, who is a legal U.S. resident, had filed taxes a few years ago, the child tax credit was automatically coming into their bank account.

But she is in the country illegally and is fearful of accepting government aid that may affect her chances of citizenship down the road. (Under former President Trump, a âpublic chargeâ rule that is no longer in effect barred immigrants who accepted government benefits from becoming permanent residents.)

When she heard about the increased payments, Puebla tried to opt out, calling the IRS multiple times.

âI think all of this is a scam,â said Puebla, who came to the U.S. from Mexico. âI donât like getting money from the government. I feel like thereâs a catch.â

Bidenâs ambitious child tax credit, putting cash in familiesâ bank accounts soon, could cut child poverty in half. But a lot has to go right on a tight deadline.

Hermelinda Guadarrama Lopez, a single mother of three teenagers, lives in a Westlake studio apartment and was unemployed for most of the pandemic.

In March, she got a new job cleaning a bank for a few hours a day.

On the Spanish-language channel Telemundo, she saw a segment about the tax credit in which people expressed reservations about the money.

Guadarrama Lopez thought she might have to pay back the money. As an immigrant without legal status, could she really qualify for government benefits?

Someone from a Westlake organization called Central City Neighborhood Partners assured her she was eligible.

âI have heard money has gone to residents, but I have never received that type of help,â she said.

Her kids need shoes and uniforms for school. Sheâs behind on rent and has been hoping to upgrade to a one-bedroom unit.

She needs the money now. But she is thinking about checking the box to receive a lump sum later.

At a recent community fair at San Fernando Gardens, booths offered free Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, masks and hand sanitizer, along with advice on immigration issues. Organizers hoped that those who stopped by would also listen to a pitch about the child tax credit.

John Ma of Ground Game LA wrote down the names of people who would receive a follow-up referral. Other organizers knocked on doors, eventually arriving at Acostaâs apartment.

When she learned about the tax credit, Acosta had signed up online immediately. But she hadnât received any money, she told the organizers. She went to the booths and spoke to Ma.

Acosta quit her job a few years ago to care for her son, who has special needs. Both she and her husband are immigrants without legal status, and their income has been too low to file taxes.

Her husband earns about $700 a month â not enough to cover their $900 rent and summer electric bill.

A month after the event, Acosta still hadnât received the money. Ma referred her to El Centro de Ayuda for help.

In the meantime, the Acostasâ expenses were piling up. Their 12-year-old son had gotten hurt playing soccer. Acostaâs husband was staying home with the other kids while she went to medical appointments.

âThis is the only check we have the hopes of receiving,â she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.