Strong winds fanning Windy, KNP Complex fires as they burn through southern Sierra Nevada

Gusty winds blowing through the southern Sierra Nevada continue to spread the growing KNP Complex and Windy fires, which have burned more than 135,000 acres combined as they tear through steep, rugged terrain.

Furious westerly winds â some gusting up to 40 mph â fanned the Windy fireâs growth by nearly 2,000 acres in a day. The fire, raging in the Sequoia National Forest and Tule River Indian Reservation, had ballooned to 87,318 acres on Tuesday and was only 4% contained.

The KNP Complex fire, burning to the north in the Sequoia National Park, had burned through 48,344 acres and was 8% contained.

Both fires erupted Sept. 9 amid a massive lightning storm that sent dozens of bolts shooting into the dense forest, home to groves of giant sequoia trees, including the famed General Sherman tree. Since then, they have expanded rapidly through the drought-stricken vegetation.

Toxic smoke from the twin blazes have shrouded skies and triggered air quality warnings more than 100 miles away.

That gray-orange haze in the air is mostly wildfire smoke blowing in from the Windy and KNP Complex blazes burning in the southern Sierra Nevada.

âIf you had told me 2½ weeks ago that at this point, we would be less than 10% containment, I probably wouldâve said, âWell, Iâm not sure I want to hear that.â But here we are,â said Clay Jordan, superintendent for the Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

During a community meeting Monday, Jordan said fire officials were wrestling with âvery difficult decisions,â weighing firefightersâ lives and communities at risk from the blazes.

Because of the extreme steepness of the terrain and hazards posed by standing dead trees â known as snags â firefighting efforts have included significant amounts of indirect attacks, such as building containment lines, officials said.

âYou can place firefighters in there, expose them to great risk, and have very little chance of success,â Jordan said. âYou just canât justify that level of risk.â The downside is that with indirect methods, âthe matrix of containment is not a good measure of progress,â he said.

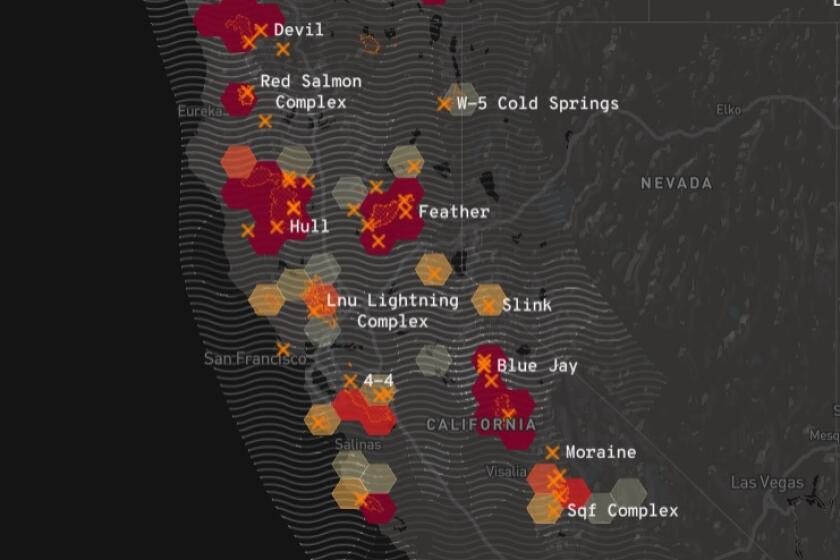

Track wildfire origins, perimeters and air pollution with the L.A. Times California wildfires map.

The benefits of indirect work can take a while to show, said Jim Mackensen, a public information officer for the Windy fire, who said intense fire behavior and rough terrain have often made direct firefighting techniques infeasible.

An infestation of bark beetles a few years ago killed a large number of drought-weakened trees, felling them and strewing their parched carcasses on the ground.

âWhen the fire gets into those areas, it sets all those logs and stuff on fire, so itâs got a tremendous amount of energy,â Mackensen said. âWe canât put firefighters right on the line to fight those fires.â

In many instances, crews instead have backed away from the edge of the fire and put containment lines off roadways or dozer lines while waiting âfor the fire to come down closer to us,â Mackensen said. He said he expected containment on the fires to increase over the next several days as the flames reach those lines.

Roughly 158 homes in the Sequoia National Park, in the Lodgepole area, and nearby communities of Three Rivers and Hartland are threatened by the KNP Complex. Personnel were prioritizing protecting those structures Tuesday, officials said.

Meanwhile, crews from Tulare County were assessing potential damage to homes and other properties in the Sugarloaf and Pine Flat areas, along the south end of the Windy fire, where flames swept through in recent days.

In California and beyond, some people are deeply in grief, stunned that flames could again imperil some of Earthâs oldest living things.

Despite fire officialsâ cautious optimism that indirect firefighting methods will pay off, albeit more slowly, thereâs general consensus that both the KNP Complex and Windy fires will continue to swell.

Years of drought have primed the stateâs vegetation to burn faster and hotter â a problem firefighters are contending with up and down the state.

A winter and spring of little rain and minimal snow runoff â followed by months of unusually warm conditions and several summer heat waves â left wildlands primed to burn fast, giving fire crews little time to get a handle on flames before they explode.

And adding to fire expertsâ concerns is the fact that much of the dry vegetation this year hasnât yet encountered severe winds, which tend to arrive in the form of Santa Anas and sundowners later in the year.

When the extreme dryness does meet strong winds it can quickly spell disaster.

Times staff writers Hayley Smith and Alex Wigglesworth contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.