She was a watchdog over L.A. politicians. But they had power over her raise

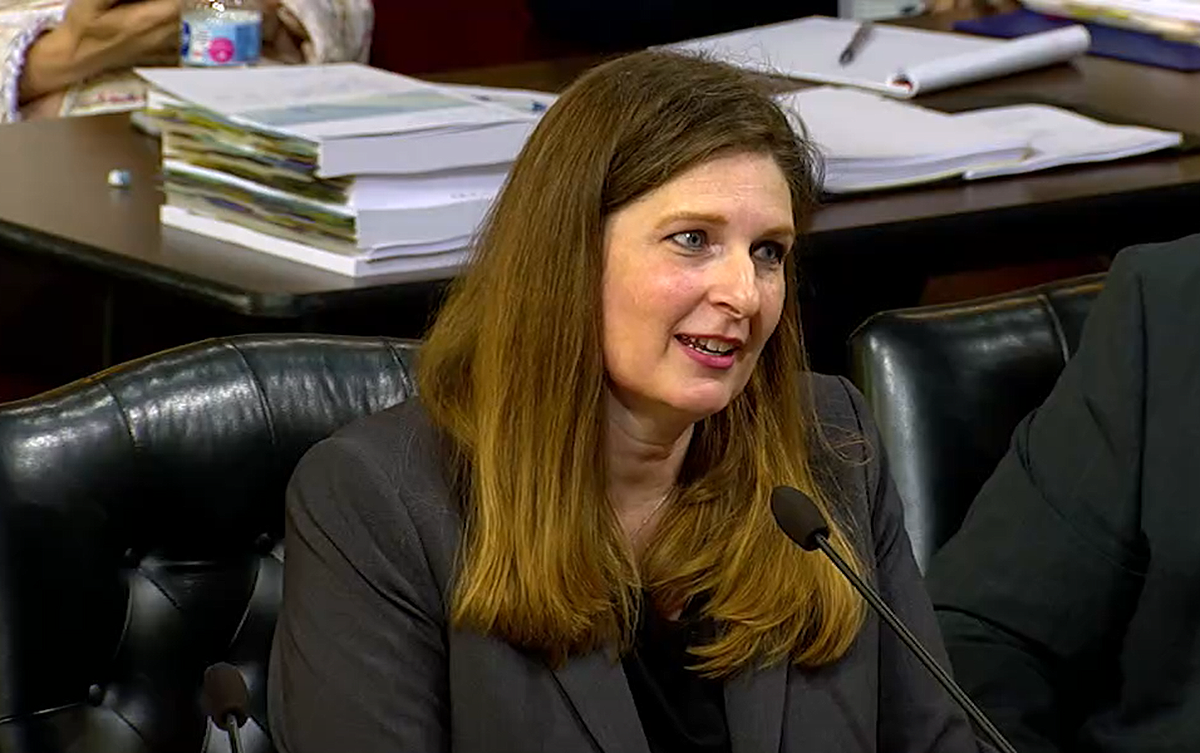

Heather Holt had an important job at City Hall and felt she deserved a significant raise.

For nearly a decade, Holt had been in charge of the Los Angeles City Ethics Commission, which serves as a watchdog over L.A.’s politicians, lobbyists and others. Her agency’s duties kept growing, and she believed the salary for her position should go up as well.

But to get that increase, she needed approval from the city’s elected officials. So she turned to a top aide to Mayor Eric Garcetti, the highest-level elected official regulated by her agency.

Holt ‚Äúwants a champion,‚ÄĚ wrote City Administrative Officer Rich Llewellyn in a December 2019 email to Ana Guerrero, Garcetti‚Äôs chief of staff. ‚ÄúShe would love it to be you.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúGot it,‚ÄĚ Guerrero replied. ‚ÄúI would be happy to have our office play that role.‚ÄĚ

Holt never received that raise, which became a casualty of the economic crisis that enveloped City Hall following the outbreak of COVID-19. But her behind-the-scenes campaign highlights an uncomfortable fact about the city’s ethics agency: It operates at the mercy of officials it is charged with policing.

Garcetti and the council have final say over Ethics Commission budgets and hiring powers. They decide whether to greenlight reform measures prepared by the agency. And they approve requests to change the salary of the commission’s top executive.

Critics question whether that power dynamic undermines the agency’s role as a watchdog.

‚ÄúIf you require Ethics Commission employees to be beholden to the City Council for their salaries, for the department‚Äôs funding, you give them no power,‚ÄĚ said attorney Grace Yoo, who ran unsuccessfully for City Council last year.

Yoo argued during the campaign that the agency needs a dedicated source of funding that cannot be cut by the mayor or council. Holt’s dependence on those politicians for her proposed pay increase only strengthens the case for change, she said.

Holt pushed for a higher salary during a period when she was receiving other types of pay increases. The Engineers and Architects Assn. struck a salary agreement in 2019 that provided Holt and thousands of other city workers ‚ÄĒ including those not represented by a union ‚ÄĒ a package of raises and one-time payments.

The agreement helped boost Holt’s total pay from nearly $224,000 in 2019 to around $247,000 in 2020, according to figures provided by Llewellyn. Still, Holt also wanted to increase the compensation for her position specifically, arguing that her pay should be set at the same level as a senior assistant city attorney.

Asked about the request for a higher pay, Garcetti spokesman Alex Comisar said the mayor did not authorize an increase for Holt or any other department head during the COVID-19 crisis. Garcetti also believes Holt‚Äôs agency provides independent oversight that is ‚Äúvital to preserving public trust in city government,‚ÄĚ Comisar said.

Additional duties

Holt did not respond to interview requests. But her push for a pay increase is spelled out in correspondence obtained by The Times through public records requests.

In those emails, Holt said her position’s duties had increased substantially over the decades. Since the position was created, the agency has taken responsibility for an array of new regulations, including restrictions on campaign donations from developers and city contractors.

Holt wrote repeatedly to Guerrero and asked for guidance on the process of changing her salary.

Guerrero, Garcetti’s top aide, told her she would help prepare Garcetti to advocate for the salary changes at the Executive Employee Relations Committee, which is made up of the mayor, City Council President Nury Martinez and three other council members.

The Ethics Commission is responsible for investigating allegations that the mayor or council members have violated ethics laws that govern political fundraising, acceptance of gifts and misuse of government resources. The agency can seek financial penalties against officials found to have violated the rules. And it routinely audits the mayor and council members’ campaign committees.

Even if Holt managed to keep her salary request from interfering with her duties, ‚Äúthe appearance of influence is a problem,‚ÄĚ said Miriam Krinsky, who served on the Ethics Commission from 1998 to 2003.

‚ÄúThe Ethics Commission needs to stay above the fray and have the trust of the voters,‚ÄĚ Krinsky said. ‚ÄúWhen they don‚Äôt have that trust, their ability to stand for what the city needs is eroded.‚ÄĚ

A former Ethics Commission staffer said she and others were told that a Los Angeles City Council member wanted more ‚Äúpermissive‚ÄĚ advice on gift laws.

David Tristan, who replaced Holt as executive director in January, said Holt followed the city’s process for reassessing the salary range for her position.

Under the city charter, the City Administrative Officer can recommend a salary increase after assessing the position’s responsibilities. That increase would then require approval from the mayor and council.

‚ÄúThe responsibilities and authority of the executive director position had not been reviewed since 1990, despite the fact that many additional duties and expanded authority had been vested in the position through the adoption of new laws,‚ÄĚ Tristan said.

Tristan said that Holt did not communicate with any elected officials about her salary request.

‚ÄėSuper weirdness‚Äô

Loyola Law School professor Jessica Levinson, who served on the Ethics Commission from 2013 to 2018, said the system left Holt with no choice but to seek the support of the mayor and council if she wanted her proposed increase to go through. But that put her in a tough position as a government watchdog, Levinson said.

‚ÄúIf you are the executive director, of course you know there‚Äôs super weirdness with having to ask for a pay raise from the officers you‚Äôre overseeing,‚ÄĚ she said.

Holt stepped down from her post in January after reaching the city’s 10-year term limit. She now works as the agency’s second-highest executive, taking the position Tristan previously held.

Tristan did not answer questions about whether it is a problem for the city’s elected officials to control his department’s budget. But concerns about the agency’s financial independence have come up before.

Earlier this year, The Times reported on the existence of a whistleblower complaint about allegations of political pressure over the agency’s budget.

In her 2018 complaint, Ethics Commission staffer Alexandria Latragna alleged that Holt told staffers they would need to soften their advice on gifts for politicians because an unnamed council member had threatened to cut their budget.

Latragna later left the agency and Holt denied being threatened by any elected official. Tristan, asked about the complaint earlier this year, told The Times that the agency always provides policy advice based on facts and the law.

The Ethics Commission was created in 1990 to help ensure that politicians, lobbyists and others comply with laws on gifts, lobbying, conflict-of-interest rules and political giving.

When L.A.‚Äôs ethics agency was being developed, a commission recommended that its funding be protected from political interference, shielding it from ‚Äúbudget battles with the political officials who are subject to its rulings.‚ÄĚ

Los Angeles voters ultimately took a more modest step, approving a ballot measure that only required the council to appropriate money for the Ethics Commission one year in advance. The idea was that ‚Äúif we took an action that made people angry, they couldn‚Äôt immediately act to cut the budget,‚ÄĚ said Rebecca √Āvila, a former executive director of the Ethics Commission.

Those protections did not prove meaningful, √Āvila said, because the council retained the power to release money to the commission each year. Llewellyn, the City Administrative Officer, said city officials set aside money in advance only for the executive director‚Äôs salary, not the entire agency‚Äôs budget ‚ÄĒ a practice dating back more than a decade, he said.

Bad timing

Holt spent more than a year in talks with city budget analysts about increasing her salary, arguing that the position should be compensated at the level of a senior assistant city attorney.

In January 2020, Dana Brown, who was then employee relations chief, asked Holt about having the president of the Ethics Commission ‚ÄĒ the five-member panel that imposes ethics fines ‚ÄĒ obtain support from Garcetti and the council president for the salary hike.

Holt replied that she had instead reached out directly to Guerrero, Garcetti‚Äôs top aide, after being told that deputy mayors ‚Äútake up the torch‚ÄĚ for department heads.

Weeks later, Brown told Holt her office was looking at recommending a roughly 15% increase in Holt’s salary, along with some back pay. The change would need to go to a committee, then to the full council for approval.

Holt repeatedly inquired with Brown about scheduling a vote on the proposal in the city’s negotiating committee, made up of Garcetti and four councilmembers. But by May 2020, the pandemic had hit and the city’s budget was in freefall, with Garcetti recommending employee furloughs.

Brown told Holt the timing for a vote was bad.

‚ÄúIf the next agenda isn‚Äôt good timing,‚ÄĚ Holt replied, ‚Äúdo you know when it will be good timing?‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúWhen this virus/furlough/budget thing has passed,‚ÄĚ Brown said.

City budget analysts did not finalize a proposal for increasing Holt’s salary, largely due to the pandemic, said Llewellyn, the city administrative officer.

Asked if the salary hike is still being considered, Llewellyn said: ‚ÄúLikely not in the short term.‚ÄĚ

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.