Barbara Ferrer mourns the 24,000 dead in L.A. County and wonders if she did enough

The pandemic was spreading fast across Los Angeles County. Barbara Ferrer was trying to stop it, but her moves were turning many against her.

Business owners lamented her lockdown orders, preachers ignored indoor worship bans, and politicians pressured her to loosen mandates. Social media lit up with hate and, in a few cases, death threats against the countyâs director of public health.

When L.A. County hit its worst moment in the pandemic during the winter surge, the barrage of anger was hurled from right outside her front door.

Protesters, screaming through bullhorns and carrying signs echoing conspiracy theories, had begun gathering regularly outside her home in Echo Park. They went without face coverings and confronted her masked neighbors.

âYou are a traitor to all the people of Los Angeles!â one man shouted from Ferrerâs driveway.

It was the kind of high-pressure churn of threats and challenges that claimed the jobs of at least 190 public health leaders across the country who have either been fired, retired or resigned during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ferrer, 65, wasnât ready to quit, and 15 months into the countyâs largest and most complex public health challenge, she is on the verge of outlasting the pandemic.

Itâs still too early to write the definitive history of how L.A. County fought the coronavirus and fully assess Ferrerâs performance. She has been among the most aggressive of California public officials in pushing for lockdowns and business shutdowns that were praised by public health experts and many residents who sent her letters of support.

Even her toughest critics, among them county supervisors, credit her for her stable leadership amid constantly shifting factors, many of which were beyond her control, such as vaccine supply levels and peopleâs personal behaviors that defied mask and other mandates. Her allies praise her for standing up to business pressures to keep the economy open, something they believe saved lives.

But in a county that at times became the epicenter of the pandemic â with some of the highest death and vaccine disparity rates in the country â Ferrerâs legacy will long be scrutinized with a critical eye.

The countyâs efforts to slow the virus with social distancing and restrictions on gatherings, so criticized by business owners devastated economically by the lockdowns, showed signs of success, especially early in the pandemic.

But L.A. County was then hit by a winter surge that pushed hospitals to the breaking point. And the toll on L.A. Countyâs poorest neighborhoods was devastating, while those living in more upscale areas saw much less illness and death.

Such outcomes have prompted some calls for the city of Los Angeles to break away from the county health department and establish its own, as is the case for the cities of Pasadena and Long Beach.

âPublic health directors in general are very good data collectors. Tragically, theyâve proven to have major equity blind spots during this pandemic,â said Los Angeles City Councilman Kevin de LeĂłn, who represents some of L.A.âs hardest-hit areas.

The pandemic proved the countyâs health department is too large to meet the âunique needs of L.A.âs diverse residents,â he said.

In some ways, Ferrer is one of her own harshest critics.

A public policy scholar who dedicated her career to fighting for health equity, she led a public health effort that became a tragic example of how racial and socioeconomic inequities contributed to a massive death toll. The blame cuts across every branch of leadership, and few fault Ferrer.

âIt would be compounding the tragedy to assign responsibility for the ethical shortcomings of the system to one person, or even one institution,â said Frederick Zimmerman, a UCLA professor who has studied the economics of health equity.

Ferrer wonders whether she could have better protected people living in the countyâs poorest neighborhoods, which bore the brunt of the pandemic. In Watts and Boyle Heights, for example, where more than 90% of residents are Black or Latino, 16% to 20% of residents got sick with the virus, a rate much higher than more affluent areas.

âWhen you have a responsibility and opportunity to help protect peopleâs health, and 24,000 people die, I think rightfully I should feel bad,â Ferrer said. âI think itâs OK for me to feel bad about it â because itâs devastating.â

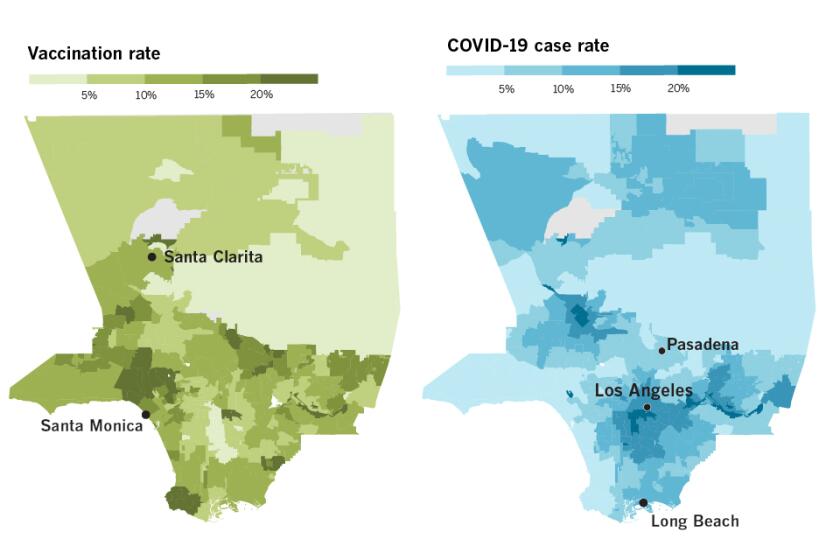

Disparities are revealed in detailed data tracking the progress of the COVID-19 vaccination effort in more than 340 neighborhoods across L.A. County.

It wasnât long after L.A. County opened its five large vaccine sites in mid-January that Ferrer noticed a troubling trend.

Ferrer spent weekends at vaccination sites where she walked among the lines of cars, volunteering alongside her adult daughter. The Puerto Rican-born Ferrer chatted up people in Spanish and English, posing for socially distanced selfies and joking that before the pandemic only a handful of people in the county knew who she was.

But the first day Ferrer worked at the Downey site, there werenât many Latinos or Asian Americans.

âThe majority of people who were here were white people,â Ferrer said during a recent interview at the vaccination site. âNothing wrong with everyone getting access to vaccines, but if we had set up a system that really was disadvantaging working people from getting appointments, we had to fix that.â

Ferrer spent a lifetime preparing for the moment.

Ferrerâs father was a factory worker and her mother a nurse-turned-educator. They instilled in her: âWeâre all here to take care of each other.â

In college at UC Santa Cruz, she helped organize farmworkers. Her first job out of college was advocating on Cape Cod for low-income families with limited access to the only hospital there. Ferrer later helped organize one of the first coalitions in Massachusetts that included homeless people in their discussions about solutions. They were âprobably some of the most meaningful jobs Iâve had,â she said.

After a stint leading the Boston Public Health Commission and working at the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, Ferrer came to L.A. in 2017, where she focused on social justice issues and helped launch the countyâs Center for Health Equity.

One of the centerâs goals, she said, is dismantling false narratives in healthcare. Black people have been blamed for decades for poor health outcomes when the disproportionality is actually âvery tied to racism and disinvestment in communities and not making sure people have resourcesâ to ensure good health, Ferrer said.

How those same inequities have played out in the pandemic has been stark.

During the early months of the pandemic, many Black and Latino residents did not have testing sites close to their homes, making it hard to discern where the virus was most active. Data soon showed Black and Latino residents were contracting the virus and dying of COVID-19 complications at far higher rates than white people.

Ferrer promised that the vaccine distribution would play out differently than testing, but by February, vaccine disparities were apparent. Data showed that the wealthier and whiter a community, the more vaccinated its population. In Bel-Air, Beverly Crest and Beverly Hills, 1 in 4 residents had received at least one dose by mid-February. In South L.A., the rates were far worse: Only 1 in 21 people in both Compton and unincorporated Willowbrook had gotten a shot.

Many of the factors driving the disparities were out of Ferrerâs hands. Federal and state leaders set the rules for who would be vaccinated first, and L.A. County, like the rest of the nation, received only a trickle of doses in those first few months.

Still, some of the disorganization, health advocates say, was preventable. Community clinics in L.A. County that predominantly serve working families said they werenât given enough time or instruction on how to prepare for a massive distribution effort.

âWe were given one week to figure out how to get the vaccines distributed,â said Louise McCarthy, president and chief executive of Community Clinic Assn. of Los Angeles County, which represents 64 community nonprofit clinics and health centers from the Antelope Valley to Long Beach.

âThe intentions were good all around, but this pandemic necessitated a response that our systems werenât ready to give,â McCarthy said.

The system makes it difficult for counties to reserve vaccine appointments and allows wealthier people to take advantage, L.A. County officials say.

Once data revealed large disparities in vaccine access, Ferrer did move quickly to improve distribution, taking aim at the system that was designed by the state.

She considered it a prime example of what happens when leaders donât take into account race, racism and discrimination when designing a public health strategy.

Under the system, the primary way to get an appointment was through the stateâs online MyTurn scheduling platform. That was simple enough for professionals and wealthy people with access to the internet, but it put busy shift workers and low-income people without broadband internet at a disadvantage.

So Ferrerâs team took thousands of appointments offline and worked with community groups and clinics to develop a closed system to schedule appointments for specific populations in underserved areas.

Hundreds of outreach workers walked the streets of East L.A., Boyle Heights and other hard-hit neighborhoods, answering residentsâ questions about COVID-19. The county health department started vaccinating entire families, ages 16 and older, in communities with the highest case and death rates.

To reach more older people of color, they traveled to senior living facilities, offering vaccines to anyone who wanted one.

As California opens COVID-19 vaccine eligibility to anyone older than 16 in weeks to come, outreach will remain a crucial part of the stateâs strategy.

Access to the vaccine has vastly improved for these neighborhoods. In a given week, the county sends more than half of its vaccine doses to clinics in lower-income neighborhoods with few doctors and high rates of serious illnesses. Disparities still persist, but community leaders give Ferrer credit for significantly closing the gap.

âItâs almost impossible to overcome hundreds of years of mistreatment with one outreach moment,â said Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, senior advisor to the equity-focused We Must Count coalition, adding that Ferrerâs agency and the countyâs other health agencies have made important strides in a short period of time. âWeâre building relationships that we need to maintain for a long time. That trust-building is going to take a while.â

But anger and questions remain in some quarters about whether the county could have handled matters better. Ferrer and the county bureaucracy have faced criticism for mixed public health messaging and for being, depending on whose talking, too restrictive and hurting businesses or too liberal and putting people at risk.

L.A. City Councilman De LeĂłn has now taken that criticism a step further, calling on the city to cut ties with Ferrerâs agency and start its own city-run health department. He points to the huge toll on Latino residents â many essential workers who got sick on the job and then unknowingly spread the virus in the overcrowded communities where they live â as central evidence of what went wrong.

Ferrer is quick to acknowledge the shortcomings of her agencyâs pandemic response, saying the speedy spread of the virus caught officials flatfooted early on.

âI wish then we had recognized, and we ought to have, that this was very quickly not going to be an issue for the wealthiest people,â Ferrer said.

::

The pandemic has turned Ferrer into one of the most high-profile public health figures in California. An unflappable presence at the lectern, Ferrer fielded tough questions at regular news conferences and spent weekends chatting with hundreds of people at mass vaccination sites.

For the most part, she kept her composure. But at a news conference in early December, the months of death and illness caught up with her.

Ferrer had just found out that a child had died from complications from a coronavirus-linked multisystem inflammatory syndrome.

As she discussed a slide on her PowerPoint presentation showing a trend line of the skyrocketing number of deaths, she started to cry.

The emotional display was not surprising to people who work with her. âWith Dr. Ferrer, itâs not a show,â said Kathryn Barger, who chaired the county Board of Supervisors through 2020. âShe really does have a sense of compassion and empathy toward the lives lost.â

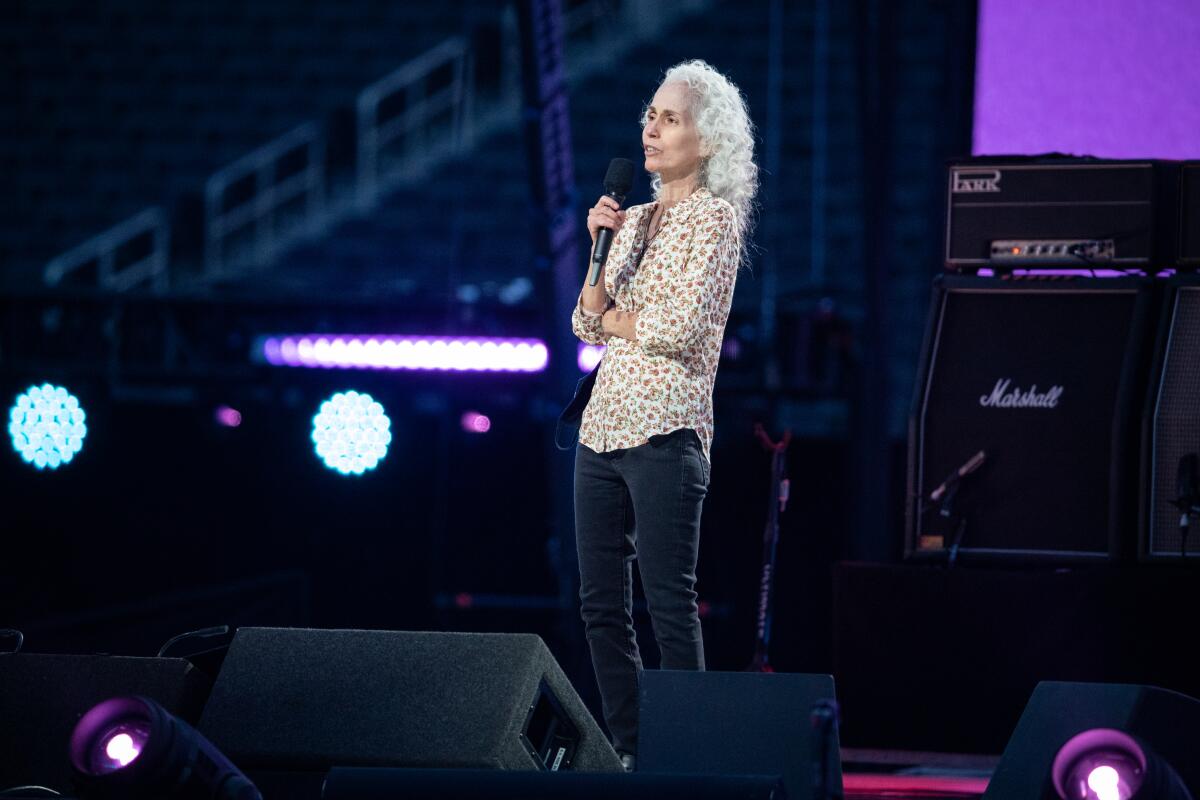

Many county residents seem to share that opinion, if her reception at a star-studded celebration in early May is any indication.

Thousands of vaccinated healthcare and essential workers gathered for âVax Live: The Concert to Reunite the Worldâ at SoFi Stadium, excited to see the Foo Fighters, H.E.R, and Jennifer Lopez, who was set to open the show with the Neil Diamond classic âSweet Caroline.â

But first came Ferrer.

With her name projected on a massive video board, Ferrer took the stage alone, prompting applause louder than even the reception for Prince Harry.

Ferrer, mask in hand, delivered the sober message that she had communicated since the start of the pandemic.

âThis has been a year filled with sadness,â Ferrer said, adding that it was important for everyone to work together to ensure the equitable distribution of the vaccine.

âSo that there are no have-nots,â she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.