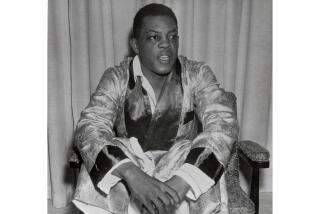

James Mills, state legislator who championed public transit, historic preservation, dies at 93

James R. Mills, a retired San Diego state legislator who never met a streetcar he wouldnât ride or a historic building he wouldnât save, died March 27 at age 93.

The San Diego native and longtime Coronado resident died of kidney cancer at a hospice facility in Bonita, family members said.

For the record:

11:39 a.m. April 6, 2021This article states that James Mills was elected to the California Assembly after the person representing the 79th Congressional District resigned to become a Municipal Court judge. Millsâ predecessor resigned from the 79th Assembly District seat.

In his 22 years as a state Assembly member and state senator, Mills was the author of legislation that created the local trolley system and Old Town San Diego State Historic Park.

The Mills Act, named after him, has been credited with saving thousands of historic residential and commercial buildings from destruction in California by reducing property taxes for owners who preserve them.

He secured funding to help restore the Old Globe theater after it burned down in 1978, and he steered appropriations for construction of the library at San Diego State and Third College (now Thurgood Marshall College) at UC San Diego. He backed local parks and bikeways.

And he did it, in a commanding baritone voice, without turning his political and legislative opponents into enemies.

âThis is a term that maybe has gone out of vogue, but he was a gentleman,â said Steve Peace, a former state legislator, âand he was a pretty consistent practitioner of having active disagreements without being actively disagreeable. It wasnât about you. It was about what you were doing.â

Mills, born June 6, 1927, grew up in a family devastated by the Great Depression. They lost their house and car when he was 5.

What happened next turned him into a lifelong Democrat: His father, a painting contractor, found work through President Franklin D. Rooseveltâs New Deal programs.

âWe were able to keep a roof over our heads during a critical period,â Mills later told the Union-Tribune.

After attending local schools, he earned bachelorâs and masterâs degrees in history from San Diego State. He served in the Army during the Korean War, taught history in middle school, and ran the Junipero Serra Museum in Presidio Park.

In 1960, when a local Assembly member resigned from the 79th Congressional District seat to become a Municipal Court judge, Millsâ then-wife, Joanna, encouraged him to run in the special election. He won.

He served in the Assembly for six years and then ran for state Senate, winning a seat that he held until 1982. He was elected senate pro tempore from 1971 to 1980, the bodyâs top leadership position.

âJim was very liberal for his time, one of most liberal members of either house, but he was a temperamental moderate,â Peace said. âThatâs why he got elected pro tem. He was a facilitator of differences.â

Mills came to regret one of the changes he facilitated. In 1966, he introduced a constitutional amendment, later approved by state voters, that made the Legislature a full-time operation.

Before then, lawmakers held a full legislative session every other year, with limited gatherings to pass a budget and deal with other pressing items in between.

The idea was that the shift would lead to a more professional operation able to respond more quickly to the needs of a fast-growing state. But after it was implemented, Mills felt that it robbed legislators of the time off necessary to reflect on what they were doing, and what they had done.

âI hope God will forgive meâ for introducing the amendment, he wrote in a 1987 book about state politics called âA Disorderly House.â

That was one of a half-dozen books Mills wrote. Others include histories of San Diego and its landmarks, and two books about Pontius Pilate. One of them, a historical novel, muses about the compromises the Roman governor of Judea faced in condemning Jesus to death.

âEvery politician that I have known, at one point or another, has given way to political pressures and done something that he or she really didnât believe was right,â Mills told the Union-Tribune after âMemoirs of Pontius Pilateâ was published in 2000.

Mills traced his interest in public transportation to his own use of it growing up in San Diego. He didnât own a car until he came home from the Army.

His 1975, legislation creating the trolley became a model for other light-rail systems around the country, but it drew some opposition from local government officials who felt it was being forced on them.

It was, Mills told Transit California in 2015. If heâd waited for local officials and the public to approve, it would never have been built. âI thought that if the people of San Diego could see it, they would like it and want more,â he said. âItâs expanded since, as I knew it would.â

The trolley now covers about 54 miles, with a new line to University City expected to open this fall.

After he left the Legislature, Mills chaired the Metropolitan Transit Development Board in San Diego for nine years. Its headquarters is named after him. He also served stints on Amtrakâs board and the California High-Speed Rail Authority.

âDad believed that government existed to serve the people, and he fought for fairness, education, environmental protections, the coastline, the climate and public services,â his daughter Beatrice Germain said. âHe was a real old-school progressive, and we are all proud of what he contributed.â

Survivors include his daughters, Germain and Eleanor Howard; his son, Bill Mills; and nine grandchildren.

Services are pending. In lieu of flowers, his family asked people to take a ride on a trolley, train or bike.

Wilkens writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune. U-T research manager Merrie Monteagudo and freelance writer Joe Ditler contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.