Suspect’s plea deal in child-murder case marks latest battle over L.A. County D.A.’s policies

- Share via

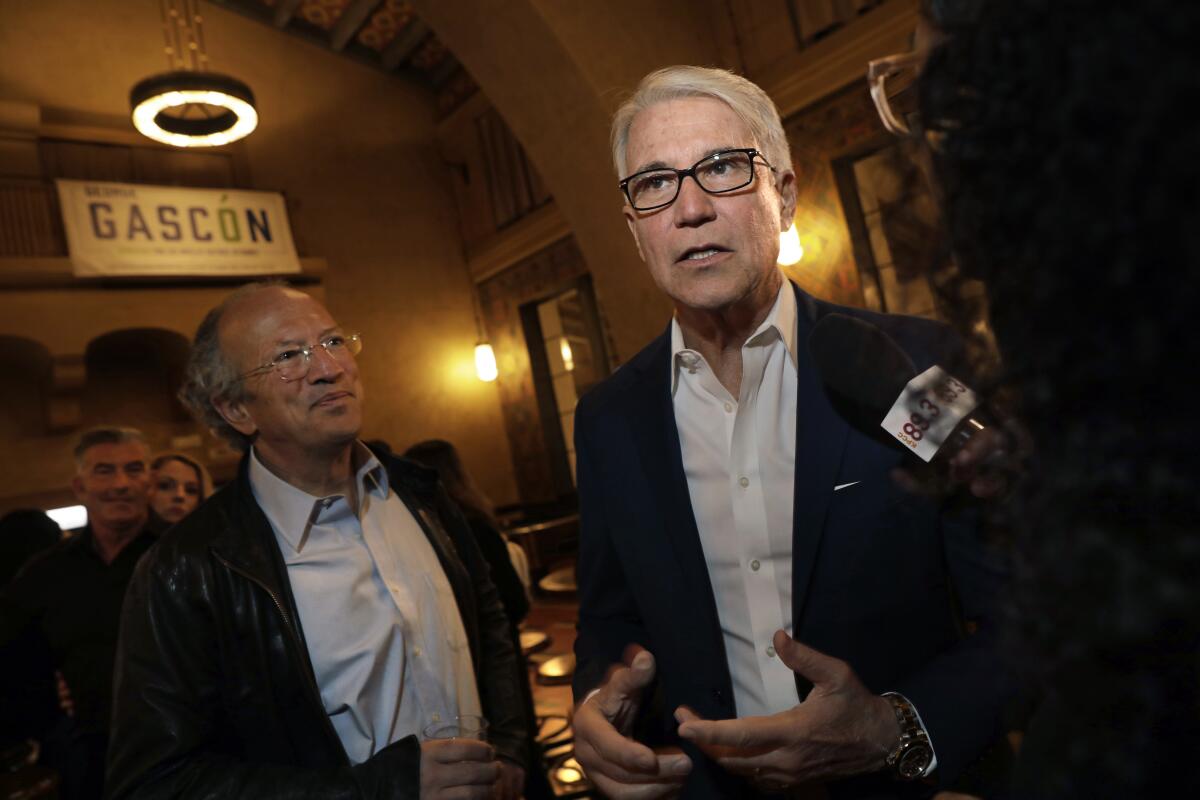

A convicted child rapist who sexually abused and murdered two young boys in Southern California in the 1980s will spend the rest of his life in prison under a plea deal reached in a Pomona courtroom Monday, ending a case that had become the latest battleground over Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón’s reformist policies.

Kenneth Rasmuson, 59, pleaded no contest Monday in the brutal murders of Miguel Antero and Jeffrey Vargo. Jeffrey was 6 years old when he was kidnapped while riding his bike in Anaheim Hills and found dead at a Pomona construction site the next day in 1981. Five years later, Miguel was abducted and stabbed to death after stepping off his school bus near Agoura Hills.

Rasmuson was linked to the slayings by DNA in 2015 and had been awaiting trial for years. The case drew renewed attention in recent weeks as a result of sweeping reforms enacted by Gascón, including edicts barring prosecutors in L.A. County from seeking the death penalty or filing sentencing enhancements that can lead to life imprisonment for some defendants.

Fearful that Rasmuson could one day be granted parole if enhancements in the case were dismissed, Orange County Dist. Atty. Todd Spitzer announced his intentions to lay claim to the case last week, filing murder with special circumstances charges against Rasmuson in Jeffrey’s slaying. Spitzer had argued that the case could be tried in Orange County because the victim was first kidnapped there.

But under the terms of the deal offered in a Pomona courtroom Monday morning by L.A. County Chief Deputy Dist. Atty. Joseph Iniguez, Rasmuson pleaded no contest to both killings and is expected to be sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole at a hearing in late April. Spitzer said Monday that he would dismiss the case he filed once sentencing is complete.

Spitzer’s move was the latest sign of a growing fracture between elected progressive prosecutors and more traditional district attorneys in California. In recent weeks, prosecutors in San Diego and Sacramento have also sought to claim jurisdiction over cases filed in Los Angeles and San Francisco due, in part, to what they see as policies that are too lenient toward defendants.

In an interview Monday afternoon, Iniguez accused Spitzer of political grandstanding. Days before Spitzer filed charges in the Rasmuson case, an L.A. Superior Court judge ruled that some of Gascón’s reforms, including his edict ordering prosecutors to dismiss nearly all sentencing enhancements and special circumstances, were unlawful.

Under California law, a defendant convicted of murder with special circumstances can only be sentenced to life without the possibility of parole or death. Gov. Gavin Newsom placed a moratorium on executions in California in 2019, and Iniguez said the motion to dismiss the special circumstances allegations against Rasmuson had been withdrawn before Spitzer got involved in the matter, making the Orange County prosecutor’s move hollow.

“He had already filed his case. He had already committed to his publicity stunt ... this was a D.A. who was eager to act without all the facts,” Iniguez said of Spitzer.

Spitzer said Monday that he believed Gascón’s office only entered into the plea deal because of the pressure brought by his filing. Spitzer scoffed at Iniguez’s claim in court that the plea had been in the works for “months,” pointing to a January court filing seeking to dismiss the special circumstance allegations, which would have eliminated the possibility of a life sentence.

Speaking outside the courthouse, Spitzer said he hoped Monday’s outcome highlighted the problematic nature of Gascón’s policies, which he said are overly broad.

“I really do hope this is the hallmark case … to prove once and for all that those special directives are seriously misguided,” Spitzer said of Gascón’s policies. “They do not take into consideration the background of the defendant, the age of the victim, how the crimes were perpetrated, the number of victims. It is a cookie-cutter approach to justice.”

Rasmuson had served 17 years in prison for kidnapping and sodomizing a 3-year-old boy from downtown Los Angeles. He was last released from prison in 2007 and had been living at his family’s residence in Idaho before his arrest in connection with the murders in 2015.

Jeffrey’s mother, Connie Vargo, said she feared Rasmuson might have been released early if not for Spitzer’s involvement.

“I’m afraid that the outcome might have been that they dismissed the special circumstances … which means he could have possibly gotten out in 14 or 15 years,” she said. “Imagine that a murderer, a child molester, a deviant to society. I’m just glad that that didn’t happen.”

Gascón’s critics often argue his refusal to seek life sentences will lead to situations where murder defendants receive relatively short prison stints, as they could become eligible for parole after serving 20 years under California’s elder parole law. Gascón has also barred prosecutors from attending parole hearings, which critics say will lead to an increase in releases.

But records show California’s parole board has one of the lowest release rates in the nation, granting parole in just 16% of the nearly 7,700 hearings that were scheduled in 2020, though that number factors in hearings that were waived, postponed or canceled. The true grant rate rises to 32% when only including hearings that actually took place, according to a Times analysis.

While Spitzer and others questioned Gascón’s commitment to crime victims Monday, Gascón said it was actually Spitzer who risked causing the families of Rasmuson’s victims additional pain by seeking to extend the case for no practical purpose.

“The defendant was always facing life in prison, making the rhetoric from tough-on-crime voices incredibly dangerous and entirely removed from reality. Splitting this case up or seeking the death penalty in a state with a moratorium would have dragged the victims through decades of legal proceedings for an execution that is exceedingly unlikely to be imposed,” he said in a statement. “Spending exorbitant amounts on a death penalty prosecution that is ultimately just for show would force the families of these victims to relive their trauma through decades of litigation.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.