SELMA, Calif. â The van rattling down a field road stood out even in a cloud of dust, its paint job the colors of birthday cake frosting, Christmas tree lights, red-purple-yellow-blue confetti.

A party van helps when trying to reach farmworkers in dark pandemic times. But Ricardo Castorena, 47, found that out by accident. Heâd only been trying to get free gas when he made the deal with the radio station.

In March, when the pandemic first closed bars and festivals, the sales manager of Radio Lazer KLUN-FM 103.1 feared the station would lose name recognition â a name announced in promos by a galloping telenovela voice backed with the sounds of a laser-gun battle.

He knew that Castorena went to the fields each day with his small nonprofit group, Binational of Central California, and that he had a witty, outgoing personality. The manager told Castorena, who was teaching Chicano and Latino studies at Fresno Pacific University, that if he would promote the station, it would provide the van and an unlimited gas card.

Castorena became the radio host El Profe. He has put 25,000 miles on the van since March.

Once he ditched his organizationâs old white van â which screamed âfedsâ and alarmed workers and farmers alike â he found a warmer welcome. For decades, Spanish-language radio stations have hosted morning coffee in the fields. Now that Castorena carried giant speakers, people stopped asking him to explain his presence.

At the beginning, his goal was to deliver 50,000 masks provided through a state grant. But being in the fields, he can start conversations, looking for how best to help. Because what people give is not always whatâs desperately needed.

Most workers have coats; socks and gloves wear out faster. When Castorena conducted a survey asking workers about their needs, the top answer was toothbrush and toothpaste, followed by a toy for their children. He tries to get balls and dolls to keep it simple.

He keeps the initial conversations light. Heâs good at a quick laugh and icebreaker.

âHey compadre â let me give you the mask with the polka dots. You can never go wrong with polka dots.â

People joke back. âHey there, good to see you, QuinceaĂąera,â they tease him.

On this day, Castorena started at a food giveaway in Riverdale, a community some 20 miles south of Fresno. Bright yellow crop dusters roared low over the parking lot where volunteers packed cheddar cheese, vegetable oil and canned goods.

Isabel Solorio said she asked Castorena to come because the prior weekâs giveaway âtruthfully felt depressing.â

Most of the volunteers who had handed out the government staples, and fruit donated by a local grower, were short on groceries themselves. The people who signed up for the boxes were given numbers so they didnât have to wait. But there had been a line of vehicles before the gates opened because people feared the food would run out.

On this day, vehicles, mostly pickup trucks, were lined up to the end of the road and Solorio was still trying to figure out how to get food to volunteers too proud to ask. But Castorena had brought the party (as well as masks).

âYouâre at risk every day out here. But you have to turn on a light in a dark room. I just want to try to be that light.â

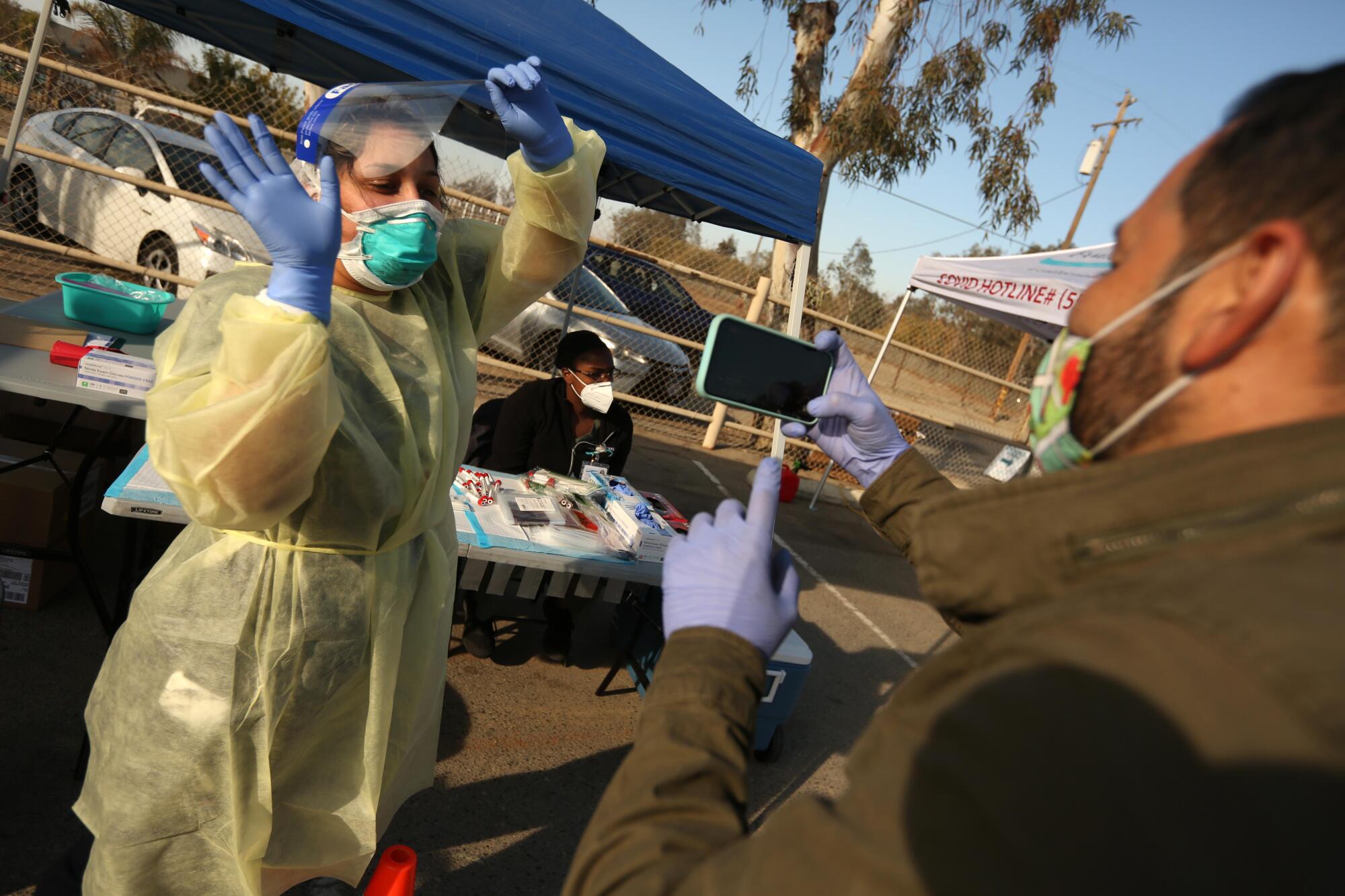

— Galilea Tafoya, medical assistant administering coronavirus tests

Latin superstar Bad Bunny thumped over the speakers. How could 20-year-old Galilea Tafoya, who was administering free coronavirus tests, not move her feet?

Castorena noticed. With a wink, he said, âLetâs see her really dance.â

He put on âLa Chonaâ by Los Tucanes de Tijuana, an anthem for a generation of kids of Mexican heritage who grew up being told baila, mijo â dance, my child â when the song would come on.

Tafoya â masked, shielded, gloved â turned up her energy. Her yellow disposable isolation gown twirled around her.

In September, the clinic where she works as a medical assistant had asked for volunteers to be coronavirus testers, warning the work could be dangerous. A month into the job, she fell ill and could barely rise from her bed for more than a week.

âYouâre at risk every day out here,â she said, still dancing. âBut you have to turn on a light in a dark room. I just want to try to be that light.â

Solorio danced too. And the man bagging potatoes and the people behind their steering wheels moved to the music.

âI get a lot of joy out of this,â Castorena said. âSomeone can say, âHey, thatâs my songâ and forget their worries for three minutes. All we can do is try to create a little joy and laughter amid all the drama.â

He walked the line of trucks handing out masks and jokes. He complimented Alondra Aguilar on her mask embroidered with intricate flowers. The mask didnât hide her smile.

Aguilar, 33, waits tables at a restaurant in Lemoore. Two of her cousins died of COVID-19 this year. She worries when sheâs at work; she also worries during the times the restaurant is shut down. She has an 18-month-old daughter to support.

Last month, Aguilar collapsed, gasping for breath. She thought it was her heart. But an emergency doctor said it was a panic attack.

After the last of the food was distributed, Castorena packed the speakers and drove north to the fields outside Selma.

Turning off the public road, he drove between rows of pear trees espaliered on slanting trellises, framing the horizon as a blue triangle. He was on his way to meet a particular crew. But when he saw a group of women pruning, he stopped to joke around and hand out masks in childrenâs sizes.

Farther on, he stopped to visit a crew taking a break next to cherry trees. The men seemed uneasy when he approached. Slowly he got the group talking and laughing, except one man sitting on the fender of a car, who never raised his eyes.

Castorena pointed to the phone number painted on the van and told the men that if they had questions or needed help â or, hey, wanted to hear a particular song â to call or text.

Out of their earshot, he predicted that he would get a message from the silent man within 15 minutes. The number on the van is linked to his phone. He said that when someone doesnât interact, he can sense whether they just want to be left alone or are in such despair that they canât lift their head.

Back in the van, he phoned a mother and daughter making burritos for him to take to the field, coordinating a day for pickup. They were not part of an organization, just two women who wanted to help. Some of the masks he was giving away were from a woman in Fresno who sewed them from pillowcases she bought, ironing them and putting them in separate plastic bags. Within 10 minutes, the text he had predicted came. Castorena pulled over to message that he would call within the hour.

The workers he had been looking for were clearing a field. They were in the distance, dwarfed by bulldozed earth. Castorena walked with them as they picked up roots and rocks. He threw out questions with the chattiness of a late-night host and got them to smile for selfies.

Jose Lozano, 34, had asked Castorena to meet them and give masks to his co-workers. Lozano has lived in Fresno since he was 10, always hiding because he isnât a citizen. For a while he had a successful recycling business. But a few years ago the price of metal suddenly dropped, and a truckload that would have brought $200 was worth $10. He went to work in the fields.

He had met Castorena at a free cookout in the fields earlier in the month. One of the volunteers, a woman from L.A., had told Lozano, âThank you for putting food on my table.â

âThat was the best part,â he said. âWe donât hear âthank youâ very often.â

Back in his van, Castorena called the man who had reached out.

The man had come from Washington in March with his family, following the crops. At first, the usual jobs were unavailable as crews were cut to skeleton staffing during the pandemic. Only recently had he found work pruning. At home, he had a wife and two children, one autistic. The family had run out of food days ago and was facing an eviction notice.

Castorena filled out the paperwork for the man to receive an emergency grant of $250, from a fund thatâs near depletion and one of the only sources of public aid for workers living in the U.S. illegally. The money would arrive in a week. He brought the family bags of food. It was mostly snacks, but it was all that he had left to give and hopefully would hold them over.

That day, after dropping off the food, Castorena came to a decision on a dilemma heâd been grappling with. He would quit his teaching job. His organization has become a bridge between people in the fields and bigger organizations and anyone else trying to help. If he had not been in the field that day, he asked himself, what would have happened to this family?

He has taken the van to the fields six days a week since March. If he were to return to teaching next semester, it would drop to three days.

His wife, Claudia, is a partner in the enterprise. They get up at 5 each morning to have coffee together, but also so she can ask him whom he was exposed to and plot that dayâs trips.

Nine years ago he was treated for testicular cancer, which puts him at high risk if he gets COVID-19. He always wears a mask and spritzes hand sanitizer as if it were cologne.

His father was once one of the abandoned children selling Chiclets to tourists at the border. Castorena said if anyone ever had a reason to turn out mean, it was his father. But instead, he said, his father is the kindest person he has ever met.

His father, also named Ricardo Castorena, now manages a big farm near Fresno but still does field work. He was the first in their family to become a U.S. citizen. Castorena was the first to go to college. Now their extended clan includes nurses and lawyers and other professionals.

Some of them donât think much of Castorenaâs plan.

âThey think Iâm going back to the fields,â he said. âBut every day I feel like I can help the kid my dad used to be.â

He can switch languages and cultures quick as a blink, one moment sounding like a professor, the next joking around in the slang and rhythms of the fields.

He said he knows his wife is worried about the cut to their income.

âBut until this thing is over, I feel like I donât have a choice,â he said.

In the fields of the San Joaquin Valley during the pandemic, a party van is one of the few beacons of light.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.