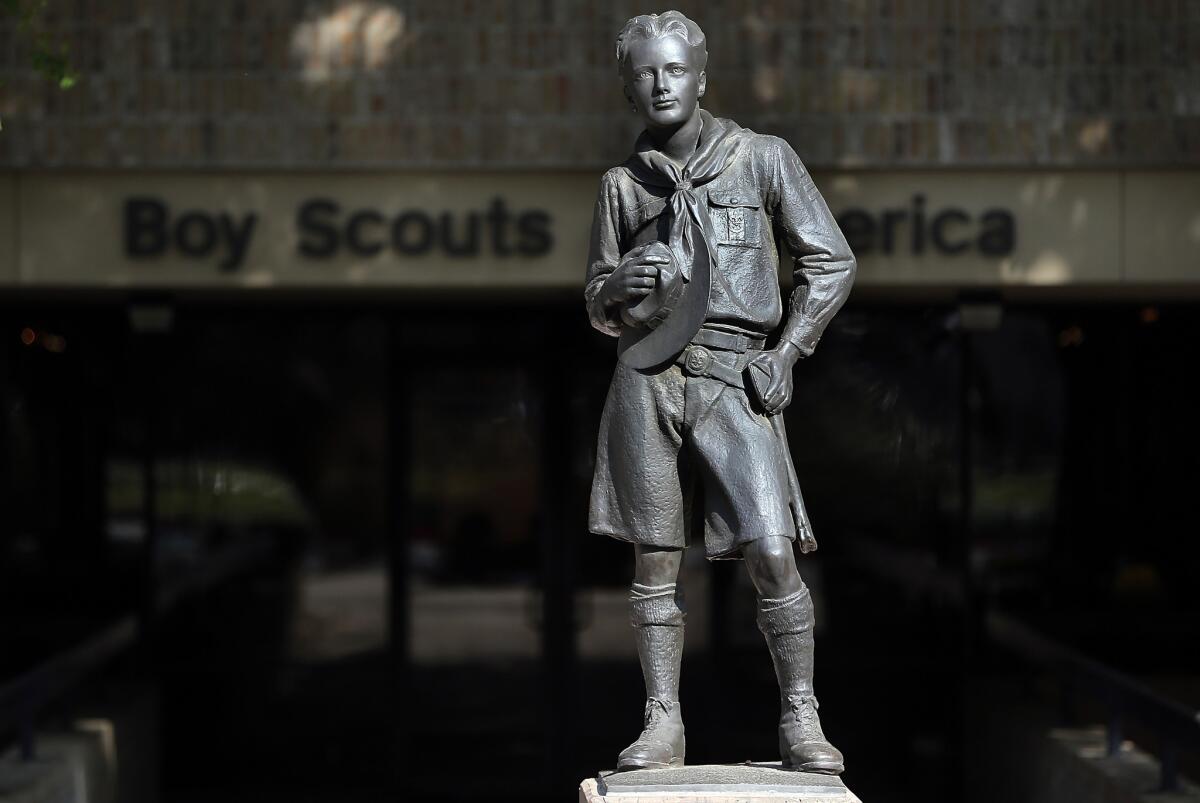

Thousands file sexual abuse claims against Boy Scouts as deadline in bankruptcy looms

- Share via

Faced with a looming deadline next month, thousands of accusers have submitted sexual abuse claims against the Boy Scouts of America in a bankruptcy that could cost the youth organization and its insurers hundreds of millions of dollars — or more.

The Scouts, which filed for Chapter 11 protection in February amid declining membership and an onslaught of new abuse lawsuits, will not say how many claims have been submitted to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Delaware.

But some plaintiffs’ lawyers say claims continue to pour in, predicting that tens of thousands will meet the Nov. 16 deadline. The massive response, they say, suggests a far broader abuse problem in Scouting than has been previously recognized and could drastically reshape the 110-year-old youth group.

“When this bankruptcy is finally resolved, the Boy Scouts will not be the same Boy Scouts of America,” said Paul Mones, a Los Angeles attorney who sits on a committee in the bankruptcy proceedings that represents victims.

The Chapter 11 action is intended to allow the Boy Scouts of America to reorganize and restructure its finances while continuing to operate. The same strategy for protecting assets against legal claims has been used by more than two dozen Catholic dioceses caught up in the church’s sex abuse scandal.

The Scouts’ bankruptcy promises “to dwarf anything we’ve seen in the Catholic Church,” said Timothy Kosnoff, an attorney with Abused in Scouting, a coalition of law firms that has aggressively marketed itself to abuse survivors through internet and television advertising.

His group has signed up more than 10,000 clients, including 1,000 in a single recent week, Kosnoff said, adding that he would not be surprised to see the total claims in the bankruptcy reach 50,000.

That number would eclipse previous official estimates. Last year, a researcher hired by the Scouts to analyze internal records from 1944 to 2016 said she had identified 12,254 victims.

“There are more claims in this bankruptcy than in all of the Catholic Church bankruptcies combined,” Kosnoff said.

The bankruptcy put an automatic hold on hundreds of pending lawsuits while a potential global settlement is negotiated. It also required new abuse claims to be handled in that venue rather than in state courts, where the Scouts faced a wave of new sex abuse lawsuits after several states, including California and New York, expanded legal options for childhood victims to sue.

For decades, the Boy Scouts of America has closely guarded a trove of documents that detail sexual abuse allegations against troop leaders and others.

Only those claims submitted by the Bankruptcy Court’s “bar date” of Nov. 16 will be eligible for funds from an anticipated victims compensation trust.

The Boy Scouts of America, which has apologized “to anyone who was harmed during their time in Scouting,” conducted its own public outreach campaign this fall, urging victims to file claims. The process includes filling out a 12-page questionnaire, which does not require an attorney to submit.

“The BSA is committed to fulfilling our social and moral responsibility to equitably compensate victims who suffered abuse during their time in Scouting while also ensuring that we carry out our mission to serve youth, families and local communities for years to come,” the Boy Scouts said in a statement.

“The bar date marks an important milestone toward meeting those objectives and sets a clear timeline for victims to come forward and later seek compensation from the BSA’s proposed compensation trust,” it said.

After Nov. 16, the claims are likely to be vetted and prioritized, but the process for doing that has yet to be defined, plaintiffs’ lawyers said. The size of the compensation pool also has yet to be determined, along with how much of it will be funded by the Scouts or their insurers.

Some of the Scouts’ insurers have refused to cover payouts in sex abuse cases, contending that the organization could have prevented the abuse that led to the claims, court records show.

Plaintiffs’ lawyers note that with tens of thousands of claims, even a modest payout for each could reach into the billions of dollars. If 30,000 claims are paid at $10,000 each, for example, the total would be $300 million. But at $100,000 or more each, the total would soar to $3 billion or beyond.

In addition to its liability from abuse claims, the organization has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, which ruined this year’s camping season and the revenue it would have generated, and by the departure of Scouts in troops sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has cut ties to the program.

At the time of the bankruptcy filing, the Scouts’ national organization had assets of more than $1 billion. Among contentious issues in the bankruptcy are billions more in real estate and other assets held separately by local Scouting councils.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys say lawsuits against the Scouts numbered well into the hundreds when the bankruptcy was filed, but the organization has not disclosed how many times it has been sued or how much it has paid out in settlements and judgments.

Many of the lawsuits came in the wake of the Los Angeles Times’ publication in 2012 of internal Scout records involving about 5,000 men on a blacklist known as the “perversion files,” a closely guarded trove of documents that detail sexual abuse allegations against troop leaders and others dating back a century.

The Times’ yearlong examination of the files documented hundreds of cases in which the Boy Scouts failed to report accusations to authorities, concealed the allegations from parents and the public or urged admitted abusers to quietly resign — and then helped cover their tracks with bogus explanations for their departures.

Los Angeles Times review of Boy Scout documents shows that a blacklist meant to protect boys from sexual predators too often failed in its mission.

Accusers cited the files — formally known for decades as the “ineligible volunteer files” and now called the Volunteer Screening Database — as evidence the organization knew of pedophiles in its ranks but failed to protect children.

Mones, the L.A.-based lawyer, used about 1,200 of the files in a Portland, Ore., trial to win a landmark $19.9-million verdict against the Scouts in 2010 on behalf of a man who was sexually abused as a boy in the 1980s.

Mones and others have long insisted that the files reflect only a fraction of the abuse that has occurred in Scouting. They note that most offenders were accused of multiple incidents of abuse and that many were never reported. The Boy Scouts of America also has acknowledged destroying an unknown number of files over the years.

The flood of new claims prompted by the looming deadline provides further evidence that the extent of the abuse was understated, Mones said.

“I think it shows that even for me, who has been doing this for all of these years, the problem of abuse in the organization is so much bigger than even those of us who thought we knew what we were talking about thought it was,” he said.

Many of the new claims are based on allegations of abuse by troop leaders and others who are not named in the files. Those making the new claims range in age from 8 to men in their 80s and 90s, lawyers said.

Gilion Dumas, a Portland, Ore., attorney who represents abuse victims in California and several other states, said she has been contacted recently by more than 100 former Scouts, most of them men in their 50s and 60s who have never told anyone about their ordeals.

“So many are calling to say that these things happened in Scouts and they realize this is the only chance they have to have their say and tell their story and get justice for what happened to them when they were kids,” she said. “They know that if they don’t speak now, they won’t be heard.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.