These doctors brought a shuttered L.A. hospital back to life to fight coronavirus

The wave started in early March. The novel coronavirus was spreading across Los Angeles County, and local hospitals were unprepared.

Public health officials feared the worst. The news from Italy and New York — the mass graves and morgue trucks — was clear. They needed more beds.

So they planned.

The hospital ship Mercy sailed to San Pedro to treat the uninfected sick or injured. The Los Angeles Convention Center was prepped as a field hospital, and the St. Vincent Medical Center reopened.

The facility had closed in January, a victim of Verity Health System’s long bankruptcy. Lying just west of downtown Los Angeles, the sprawling campus was deserted, doors locked, 366 beds empty, with the virus creeping through the city.

On March 19, Dr. Jamie Taylor got a phone call.

The state was negotiating with Verity to lease the property, and her longtime colleague Dr. Anand Annamalai was putting together “a SEAL team dedicated to COVID.”

St. Vincent was to be known as the Los Angeles Surge Hospital, or LASH. Would she be interested in opening an intensive care unit for COVID-19 patients?

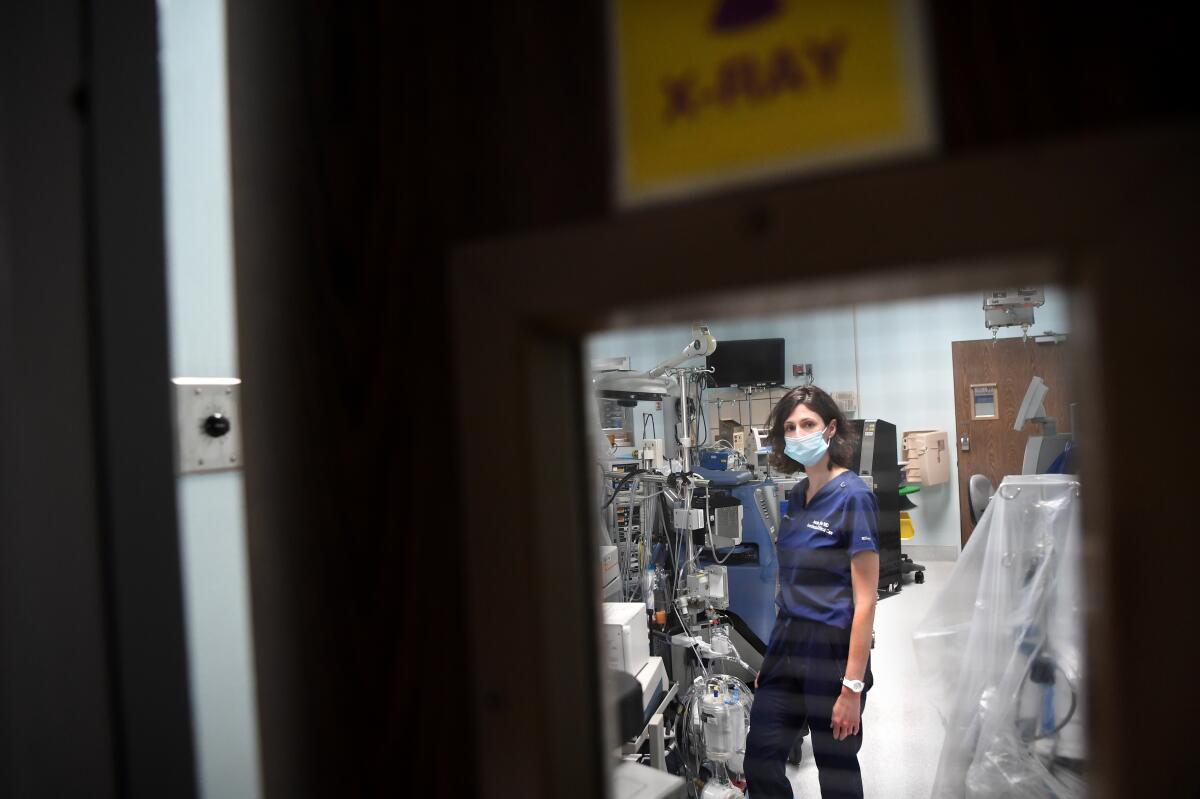

Taylor, 43 and a veteran of ICUs in California, New Jersey and New York, had experience treating severely ill COVID-19 patients at a hospital in Culver City. But that wasn’t the only reason she was being asked.

She and Annamalai had worked together at St. Vincent for almost two years starting a liver transplant and oncology program, which ended in November when Verity decided to sell the property. (Five months later, Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong purchased the medical center from Verity for $135 million. Soon-Shiong also owns The Times.)

“Our swan song [at St. Vincent] had a bitter taste,” Taylor said. “It left all of us with a big hole in our stomachs about what was happening.”

She now had an opportunity to chase that bitterness with something sweeter. The hospital that could not pay its bills had carte blanche to fight this new disease.

Within days of Annamalai’s call, the state and Verity signed a six-month, $16-million lease. Kaiser Permanente and Dignity Health would help set up the facility and offer oversight and guidance once it was up and running. VEP Healthcare would provide physician services, and Annamalai, Taylor and nearly 35 other doctors signed up.

By the time LASH closed on May 22, it would serve some of the poorest, sickest people in Los Angeles County and shore up the county’s patchy hospital system. It would cost millions, last 39 days and treat 64 patients.

Created from scratch, this pop-up hospital brought hope to patients and families, and for its doctors and medical staff, it represented a rare opportunity to create their own healthcare system and practice medicine unconstrained by medical corporations and insurance companies.

“LASH,” Annamalai said, “was a clinically led socialistic system.”

::

Taylor’s first day back on campus was April 2.

Walking empty corridors, she imagined St. Vincent’s final week as Verity shut it down: patients transferred to other facilities, staff emptying rooms and filling boxes with supplies.

Now those boxes had to be unpacked and the equipment inventoried, a triage of what could and couldn’t be used. There was no better place for them to begin, Annamalai said, than “rolling up their sleeves and grabbing a mop.”

To create his SEAL team, Annamalai, 41, turned to friends and friends of friends. They had less than two weeks to get ready. Working late into the night, the doctors and specialists lived on pizza and one another’s encouragement. Their motto: “Just get it done.”

Staff from Kaiser and Dignity joined them stringing ducts for an air-filtration system and rewiring telephone lines. They sealed ICU rooms with plastic sheeting, rolled in beds and laid out mattresses.

They tested monitors and ventilators, and they sorted supplies: bottles of sodium chloride, Foley catheters, endotracheal tubes, disposable stethoscopes.

They practiced donning and doffing personal protective equipment and created protocols for disinfecting themselves, containing outbreaks, and eventually, for helping families visit dying patients.

“There was not enough time to see the forest for the trees,” Taylor said, “because we were in the thick of it, chipping away at six tasks at a time.”

Annamalai, a specialist in transplant and cancer surgeries, had worked in Central and South America helping under-financed hospitals build patient capacity. He applied those lessons to LASH.

The surge hospital would not have an operating room, which required a more complex level of care. Instead, there would just be the ICU and units for patients under observation and in recovery. Medical staff set up shop on the fourth floor, and they began with 31 beds.

As the opening drew near, Taylor felt a pang for what St. Vincent could have been. The stairwells had never seemed so clean.

More than 400 positions — from intensive care specialists to security guards, nutritionists to chaplains — needed to be filled. Applications came from as far away as Florida, Texas and Arkansas. For hires from local hospitals, LASH was a double shift.

Ryan Barnette, 37, signed on early. An ICU doctor at County-USC Medical Center, he was drawn not just by the urgency of the pandemic, but also by the challenge of opening a closed facility and mobilizing a staff to care for patients who might otherwise die.

Working at both hospitals, he put in 70 hours some weeks. Sleep became a luxury for the doctor who liked to think of himself as a guy not afraid of “running into a burning building.”

::

Every time the county’s Medical Alert Center wanted to refer a patient to St. Vincent, Taylor’s cellphone rang with Thievery Corporation’s “Lebanese Blonde.”

She listened to the assessment. If a patient had COVID-19 but was pregnant or had a heart condition or any diagnosis other than respiratory distress, they were turned down. She had to be sure they could provide proper care.

Decisions were made within 24 hours, and before long Taylor was accepting up to five patients a day.

The first was a young woman who arrived intubated, wide awake and terrified.

“Respiri despacio,” Taylor said in broken Spanish, trying to reassure her. Breathe slowly.

The woman cried. Taylor held her hand.

“Todo está bien.” Everything is fine. (The patient was later discharged.)

From the beginning, the work was relentless.

Walking the ICU, covered head to toe, front to back, double gloved, masked and shielded, Taylor rediscovered something she had learned long ago.

“Medicine is not just about giving pills or doing a procedure or following a prescribed therapy,” she said. “Medicine is about human beings interacting at a vulnerable point in someone’s life. It is the acknowledgement that a patient is more than the culmination of their disease process.”

Often, in a patient’s room, away from the steady drone of air-filtration units, Taylor found a calm and an intimacy that seemed all the more precious for how menacing this disease was. With families following precautions and staying away from patients, medical staff became family by proxy.

Never was this more evident than when patients were discharged. LASH personnel lined the ramp to the ambulance bay and cheered as the patients made the sign of the cross, blessed the staff and whispered thank yous, one tear-filled goodbye after another.

Taylor estimates that 90% of their patients were Latino and that diabetes was the most common preexisting condition.

“LASH was a representation of how COVID disproportionately affects Latino communities,” Barnette said, “and a representation of how health care in these communities is struggling.”

The hospital eventually added 32 beds outside the ICU, bringing its total to 63. The daily census, however, averaged about 22 patients.

Taylor attributed the low enrollment to a number of factors. Getting the word out — that LASH was open and taking patients with specific criteria — was difficult at first, and some doctors and hospitals were reluctant to transfer patients with whom they had a relationship.

Money also played a role. Hospitals experiencing a decline in revenue due to the postponement of elective surgeries, Taylor believes, were reluctant to give up patients with insurance plans that guaranteed reimbursement commensurate with the cost of treatment.

Only three of LASH’s patients had private insurance, according to the L.A. County Department of Public Health. Twenty-eight were uninsured, and 33 were covered by either Medi-Cal or Medicare, which typically reimburse at rates lower than private plans.

::

Barnette said he was confident that LASH had saved “many, many lives.”

“That was the goal, right? Create an environment that could save lives. A lot of our patients, if they stayed at their admitting hospital, they might not have had a shot,” Barnette said, calling his time at LASH one of the most amazing experiences of his life.

Annamalai said LASH had essentially eliminated “the Goliaths of healthcare” — insurance companies and hospital administration — and for a brief, bright moment in the midst of a pandemic, doctors had a chance to deliver care on their own terms.

Taylor welcomed this change. Over the years, she had felt her idealism wane in the face of increasing bureaucratic and financial pressures.

She had watched what happened when coverage was denied or slowly deliberated. She knew who benefited when hospitals advocated invasive procedures over end-of-life care, or when doctors received a percentage of income from patients in nursing homes.

“LASH was agnostic to all that,” she said. “There was no administration saying you had to go to six committees to get a policy approved. We could write our own treatment plan and implement it in 24 hours.”

LASH was expensive, but other hospitals throughout Southern California spent millions of dollars preparing for the surge, according to John Romley, a USC expert in health economics, and their critical care infrastructure was already in place.

Operating costs for the surge hospital through May 31, according to the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, were $21.5 million which covered medical treatments and physician salaries, as well as food services and the lease on the property.

Kaiser Permanente and Dignity Health received $500,000 apiece for the salaries of their employees who were reassigned to LASH.

Those costs, the emergency services office said, were “expected to be eligible for federal reimbursement.”

Each day, Taylor said, they talked about how to work efficiently and save money, but she was also pragmatic.

“What would the cost have been if we needed LASH and didn’t have it?” she said.

::

In time, the initial COVID-19 surge in Los Angeles County became more manageable.

Taylor had expected the hospital to be open into the summer but by mid-May, there were rumors that LASH was closing

The decision by state officials came abruptly. She was scheduled to work a night shift on May 22 when she got a text at home. EMTs were transferring the last patient to Good Samaritan Hospital.

She hurried. Traffic was light. She checked in with security, put on her N95 mask and took the elevator to the ICU.

The unit was deserted. As quickly as it had begun, the Los Angeles Surge Hospital had ended.

LASH, Taylor said, had “reaffirmed my faith in medicine.”

Of the 64 patients treated there, 55 were discharged to other hospitals, rehabilitation facilities or their homes. Nine died.

Given the hospital’s unique nature and its selection of patients, a 14% mortality rate is hard to compare with other medical facilities. One hospital system in New York City recently reported a 21% mortality rate among its COVID-19 patients.

The care that LASH provided the patients was often underestimated, said Taylor. “People thought we were pitching tents and bagging patients. That was not what it was at all.”

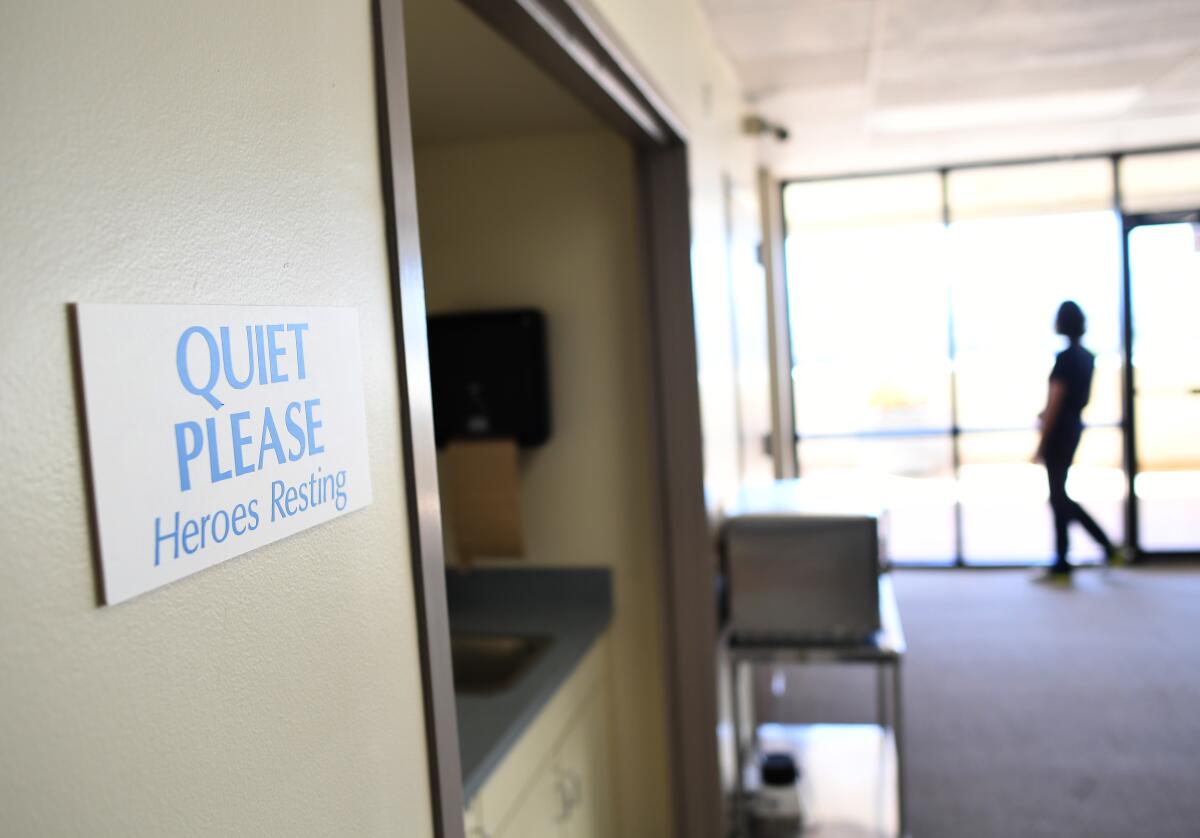

Before leaving, Taylor stopped on the 9th floor, where a break room had been set up for staff.

She didn’t know what the future for St. Vincent would be, and she didn’t believe a new surge hospital would open on the campus. That decision lies with the state, which would once again have to take on the cost.

From the county’s point of view, Los Angeles’ public and private hospitals have the ability to meet current projections, especially if the public continues to take precautions. Hospitals, as well, can increase capacity — up to 20% — by canceling elective admissions, rapidly discharging patients who no longer need acute care, changing the designation of hospital beds, and opening up non-traditional spaces for care, said a spokesperson with the Office of Emergency Management.

Taylor walked out on a balcony, which had always felt like a portal to another world, a place to escape when there was a lull downstairs.

In the late afternoon sunlight, the city was quiet.

No one knows what happened here, she thought, in this least likely of places.

As she stared across the patchwork of homes and streets to the 101 Freeway and the Hollywood sign, she knew the virus was not done with Los Angeles.

A month later, a thousand more people had died in L.A. County, cases of the disease had doubled, and the numbers continue to rise.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.