A coronavirus vaccine in 2020? Maybe. Here’s what has to go right

More than 130 labs around the world are working to develop a COVID-19 vaccine. But what would it take to vaccinate everyone by early next year?

- Share via

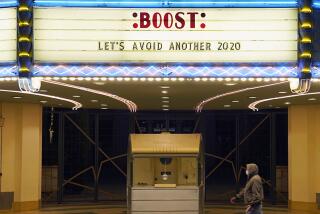

When President Trump announced last month that a vaccine against the new coronavirus could be available by the end of the year or sooner, his claim was met with a mix of hope and doubt.

The search for vaccines often ends in failure, and the successful efforts have always taken years. So it seemed improbable, if not impossible, that researchers, who began working on vaccines for the new virus in January, could discover something so elusive and do it so quickly.

But then scientists at Moderna, a pharmaceutical company, announced they had made promising early progress and claimed they could potentially have a proven vaccine by winter.

So, could a vaccine in 2020 really be in the cards?

Possibly, said Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert, and others involved in a program the U.S. government has set up to expedite vaccines that protect people from becoming infected by the virus.

Fauci and others believe they have created a doable, albeit hugely expensive, blueprint for how vaccines could be safely tested and manufactured in a matter of months. Under the plan, dubbed Operation Warp Speed by the president, the federal government has invested heavily in several vaccine efforts while also rolling out a massive testing program.

What the plan cannot address is the question that matters the most: Will any of the vaccines being tested actually work?

“All of this is unprecedented,” Fauci said in an interview. “When people say, ‘Having a vaccine by the winter, that’s impossible.’ It’s not impossible.... If the Fates have it that we have an effective vaccine and there are no glitches that are unanticipated, it is possible that we will have one in the middle of the winter. There’s no guarantee, though.”

Quick out of the gate

The quick jump that some researchers were able to make into working on vaccines shaved many months, if not more, off the typical timeline, Fauci and others said.

In January, within days of Chinese officials releasing the genetic code of the coronavirus, a team of researchers from Moderna and the National Institutes of Health had devised a possible vaccine based on a part of the virus’ genetic machinery called mRNA.

Moderna had been working for years on the technique, which has never been used to make a human vaccine, and was able to quickly apply it to the new virus. Just two months later, the first participants in a study of the vaccine were injected with it — a turnaround time that would have been inconceivable before the coronavirus.

History tells us that rushing a vaccine for COVID-19 will prove more hazardous than if it’s done right.

Scientists at Oxford University, as well as groups in China and elsewhere, also were able to get out of the gate quickly to begin tests on various types of vaccines. As of last week, 10 teams had moved beyond laboratory work to begin testing their vaccines on humans, and more than 120 others are in earlier stages of development, according to the World Health Organization.

Human trials are arduous undertakings that typically play out over several years as researchers recruit thousands of volunteers in different age groups who meet strict criteria to be injected with the potential vaccine.

Early phases of testing are meant to assess a potential vaccine’s safety. In later phases, researchers compare the rate at which vaccinated volunteers contract the virus against a group given a placebo, or dummy vaccine, to determine how much protection, if any, different doses of the vaccine provide. The process is designed to be slow and deliberate.

But with the world desperate for a vaccine or vaccines to bring the coronavirus to heel, the U.S. has looked to accelerate dramatically the discovery, manufacturing and distribution of vaccines and medicines to treat the virus that has killed more than 112,000 Americans.

Leaders of several nations last month pledged $8 billion for a similar effort to support promising vaccines around the world.

Five promising vaccines

Under the U.S. program, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has so far announced plans to spend more than $2 billion to spur the development and manufacturing of at least five vaccines considered to be promising — those from Moderna; Oxford, which has partnered with pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca; as well as Janssen, which is a part of Johnson & Johnson; Sanofi; and Merck.

The largest infusion is going to AstraZeneca, which agreed to provide the U.S. government with 300 million doses of the Oxford vaccine in exchange for up to $1.2 billion in funding, “with the first doses delivered as early as October 2020,” according to the Health and Human Services Department.

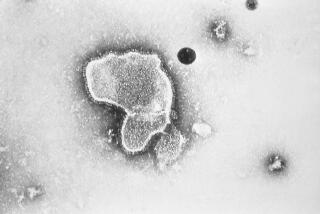

All of the vaccines in the U.S. program, as well as others under development, take aim at a spike-shaped protein on the virus that plays a role in infecting people.

Using an array of scientific techniques, the vaccines will try to relay to the immune system the information needed to recognize the protein as a threat and then respond with antibodies capable of neutralizing the protein. The nascent vaccines are appealing, in part, because each one of them could be produced at massive scale far more quickly than traditional types of vaccines.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca effort, which is also receiving funding from the British government, is made from a virus that causes common cold infections in chimpanzees and has been genetically altered to target the coronavirus.

Early tests show the vaccine may have stopped the virus from causing pneumonia in several monkeys, but it did not prevent the virus from taking hold in the animals’ noses. Results have not been released from its early tests on humans.

The Johnson & Johnson vaccine takes the same approach as Oxford’s but won’t be tested on humans until September, according to the company. Sanofi also has yet to begin human tests on its vaccine, which embeds the genetic code for the spike protein into the DNA of another innocuous virus.

Beyond investing in the vaccines, the U.S program will also oversee a plan to streamline and coordinate the testing of vaccines. The five potential vaccines will be evaluated using the same measurements to make comparisons easier, and a single, independent monitoring board will decide if any of vaccines have been proved to work.

Researchers will have access to at least 72 testing sites that have been identified across the country and an equal number in other countries, said Dr. Larry Corey, an expert in vaccine development at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center who is helping to orchestrate the government program.

The plan relies heavily on testing networks that have been built over the years for work on vaccines against HIV and other pathogens, according to Corey and Fauci. Testing sites are often based at university medical centers.

Moderna researchers have said they expect to begin the third, and final, phase of testing in July, which would give them six months to determine whether a vaccine is effective before the new year. The Oxford-AstraZeneca team is on a similar timeline.

Six months could be enough time under the framework the government has set up, Fauci and Corey said. Corey says, however, he believes it would be more realistic to start the clock once all the participants in the Moderna study have been enrolled instead of at the start, which would push the timeline into early next year.

Needed: Huge volunteer pool

If researchers can recruit a sufficiently large pool of participants in areas where the virus is infecting high numbers of people, less time probably will be needed to know if a vaccine works.

Doing so can be a challenge, especially when dealing with a new virus that is poorly understood. Where the virus will be most active when a vaccine is ready for large-scale testing, for example, is “a moving target,” Corey said.

“We have a virus that is sweeping through different areas,” Corey said. “How do we match our clinical trial sites with where the viral activity is?”

The large network of sites the government has set up is meant to guard against researchers losing time chasing the virus around the country and overseas. Sites will be pressed into service and shut down as needed. And, in the end, many sites the government pays to set up will probably go unused, Corey and Fauci said.

“We are putting a lot of money to get the sites ready ... before we even know, for example, whether a particular vaccine candidate is safe,” Fauci said. “If we discover from [preliminary testing] that, God forbid, that it’s not safe, then we’ll have invested a lot of money getting a lot of sites ready to do something that we’re not going to do.... The risk is the money, not the safety, not the integrity of the trial.”

Similarly, it is unknown whether the hot summer months in the United States could significantly suppress the virus, leaving researchers with too few options for testing whether a vaccine works.

If that happens, Corey said, researchers will probably have to turn their focus to sites in African countries, Brazil and other places that may be experiencing outbreaks. The participation of 25,000 to 30,000 people will be needed in the final stage of tests for each of the five vaccines, Corey said.

“A virus that we’ve never seen before is unpredictable,” he said. “We have to anticipate all options.”

How many doses of a vaccine could be made by the end of the year is an open question. Pharmaceutical companies have announced partnerships with manufacturing companies as well as plans to begin mass-manufacturing their vaccines before it is known if they work.

CanSino Biologics of China is in the second phase of testing a coronavirus vaccine candidate, and a U.S. shot by Moderna and the NIH isn’t far behind.

When the operations are up and running, tens of millions of doses of a vaccine could be produced each month, but getting the specialized equipment, staff and materials needed to produce the vaccines takes time.

Albert Baehny, chief executive of Lonza, which will manufacture the central component of Moderna’s vaccine, for example, said its U.S. facility would be able to make more than 8 million doses of the vaccine’s so-called active ingredients each month, but wouldn’t be ready to begin production until October.

The company’s facilities in Switzerland, which will produce about 25 million doses each month, are expected to start in December, Baehny said. And after Lonza completes its work, more time will be needed for another company to complete the last steps of the manufacturing process.

All about the data

All the logistical planning, however, will amount to nothing if none of the vaccines being supported by the U.S. program are effective at protecting people from the coronavirus. The time it will take to determine if a vaccine works is pegged to the vaccine itself, experts said.

Moderna announced in May that early tests on a handful of study participants found the vaccine had triggered an immune response that researchers believed could be effective at preventing the virus from infecting people. But it will be up to an independent board of outside experts to decide if that is actually the case for Moderna, AstraZeneca and, later, the other vaccines being tested in the government program.

To do so, statisticians on the board will perform complex calculations based on the data collected in the large trials to determine whether a vaccine has had a genuine effect that cannot have been due to chance and to estimate the specific level of protection it provides.

If a vaccine is, in fact, very effective, those results will become clear quickly because the difference between people who are vaccinated and those who receive the placebo will be stark.

In that case, the monitoring board could declare the vaccine a success, clearing the way for it to be put into use. The board probably would need longer to reach a decision about a lower-performing vaccine since it would take time to collect sufficient data to establish its effectiveness.

“None of us have a crystal ball to know where all these efforts will be on Dec. 31,” said Dr. Bali Pulendran, a Stanford immunologist. “I’m cautiously optimistic, but if there is one thing I’ve learned about the immune system, it is that we have to be humble.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.