- Share via

USULUTAN, El Salvador — They spun around the dance floor, as lighthearted and energetic as teenagers. Classmates sipped mojitos in the sticky heat. Former flames traded private smiles under trees strung with lights. The brains were there, and the athletes, the troublemakers and the do-gooders.

“How young we all look,” Mauro Adan Arce boomed into the microphone, prompting applause and laughter from the lined faces smiling back at him. In a corner, white letters backlit with red were a testament to their age: Promo 1978. Class of 1978.

It was a high school reunion, but the school they all remember is long gone. The revelers were home, but it wasn’t really home anymore.

They were 20 years old when a civil war ripped through El Salvador like an earthquake and tore their lives apart.

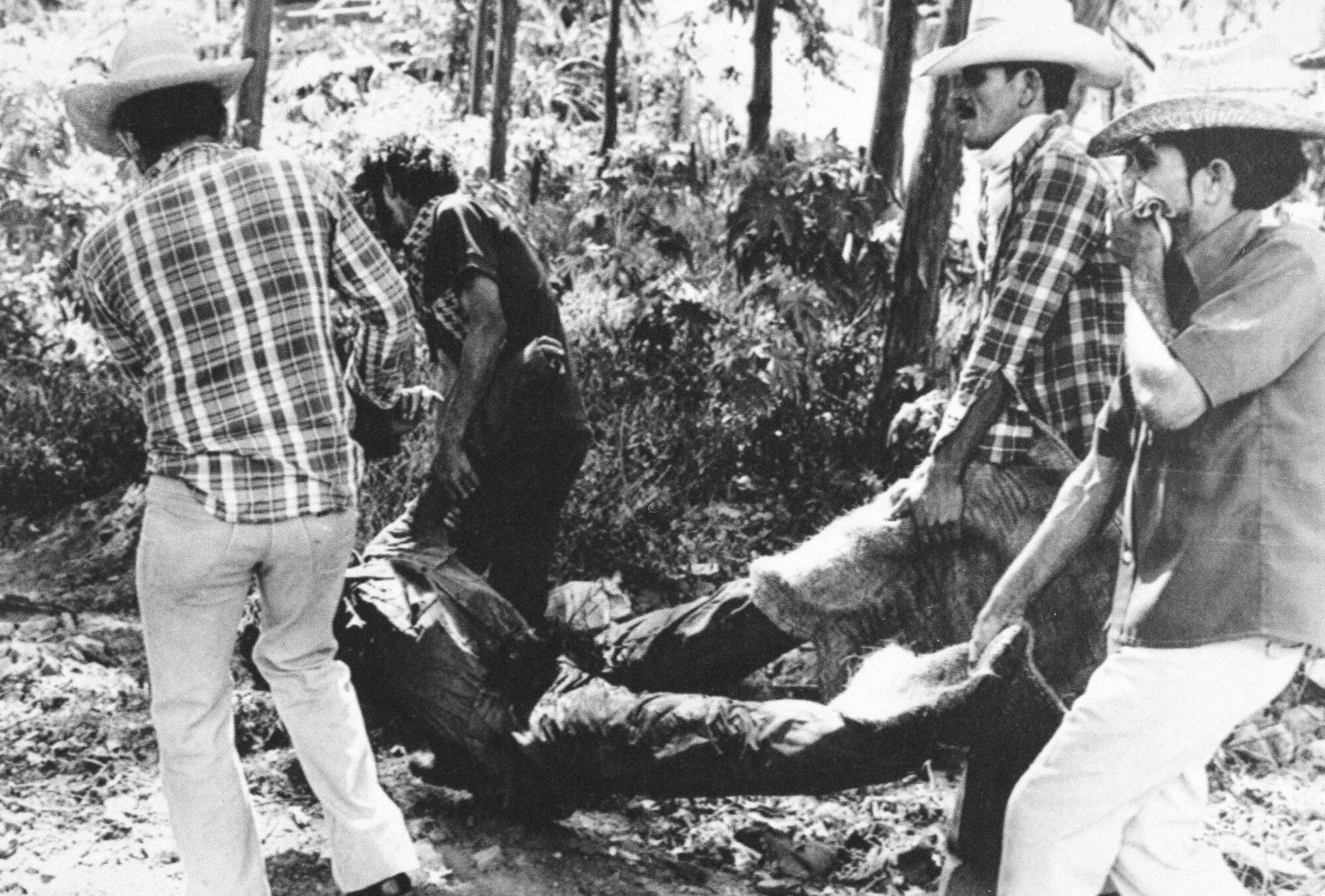

They watched death squads riddle bodies with bullets, faced down the National Guard in hope of escape, abandoned dreams to start over in Los Angeles, left behind mothers who would lose multiple sons to immigration. More than 75,000 Salvadorans died; millions more fled.

A little more than half of the National Institute of Usulutan’s graduating class remained, building lives on the ruins of their country. Twenty-five years after, they returned to Usulutan to reunite for the first time. In November, a second reunion brought about 40 of them together again.

Ricardo Alfredo Bermúdez, who left for California in 1980, recalled leaving as the conflict intensified.

“We didn’t live the war,” he said.

“Like we lived it,” said Ruti Montecino, breaking into the conversation. “The ones who stayed.”

May 1979

Promo 78 spent high school in the smallest country in Central America, affectionately called El Pulgarcito de América — the “Tom Thumb of the Americas.”

Students cut class to swim in the Río Molino, played soccer in 90% humidity and stole mangoes and watermelons from the street vendor everyone called Chepito.

Manuel Machado — a known travieso (a prankster) — threw stink bombs into classrooms and held the door shut so no one could get out. He’d hang buckets of water over doors — intended for students; they would douse teachers instead. (Janitors would get a break from mopping the auditorium thanks to Machado, who was often assigned the task as punishment.)

But there were already signs of what was coming. A crackdown on checking Salvadoran IDs. A classmate who led student protesters and later dropped out to join the guerrillas. Tortured cries filtering out of a government building, as students went to be photographed for their diplomas.

Still, that wasn’t the focus on graduation day, which happened in 1979, the year after they officially finished. That morning, the class shuffled into the pews for Mass at Santa Catarina church. After, the men sweated through their suits as they walked half a mile to the school. Mothers accompanied sons; fathers, daughters.

As they got their diplomas, the graduates felt relief.

That day, in a state of happy drunkenness, one lost his jacket. At the graduation party, where the band Espíritu Libre played, he confessed his crush to a classmate.

As graduation night crept into dawn, they asked each other what they would study and where.

“We all thought we were going to have a future here,” said Machado, pensive as he looked around at his classmates 40 years later. Like many of them, he left too.

January 1980

By the time 20-year-old Jose Alexander Navarrete arrived at the University of El Salvador, the military-led government considered the campus a center of leftist political activism. Prominent leaders of the guerrilla movement taught or studied there, and students could take classes on guerrilla tactics.

A university identification card sometimes seemed like a death certificate.

Navarrete learned to beware of the black Jeep Cherokees, the favored car of the escuadrones de la muerte. Leaving campus one afternoon in January 1980, he tensed as a Cherokee slowed beside him. He heard the click of assault rifles being reloaded.

He kept walking, but the vehicle sped up. Its passengers shot the young man in front of him. Navarrete kept his eyes forward as he passed, worried an informant would report him for helping. He could hear the man choking to death on his own blood.

In March, government troops backed by armored cars surrounded the campus. A gun battle broke out between them and leftists inside the university.

Soon after, Navarrete learned that he and a cousin were on a death squad hit list. In May, he boarded a plane in San Salvador and headed to Nicaragua, leaving behind his parents and his girlfriend of three years.

By late June, the campus was a battleground. Hundreds of soldiers in tanks, armed with machine guns and automatic rifles, stormed the university. They killed at least 15 students and shut down the school. Four months later, gunmen shot the university rector to death.

Navarrete spent about 12 years in Nicaragua, where he studied to be a lab technician. Then he spent several years in California.

By the time he returned to El Salvador in 1996, the gangs were taking over.

“We finished one war and started another,” said Navarrete, as he sat surrounded by classmates for their reunion. Before they ate, they bowed their heads in silence and thanked God to be alive.

April 17, 1980

“Fijece papa y mama que aqui no es como lo cuentan, aqui sufre uno, aunque no quiera pero asi es la vida.” “Dad and mom, it isn’t like they say it is here, here one suffers — although I don’t want to, but that’s life.”

It was one of the first letters Juan José Ramirez sent home to his parents from California. He wrote on a sheet of notebook paper. The date was inked in blue cursive at the top of the page.

Ramirez had left home soon after graduating from the National Institute of Usulutan. He was attending the university in San Salvador, with plans to be a doctor. But as the instability grew, he decided to follow his younger brother, who had left in December 1979, hoping to escape a country sliding into chaos.

The day he reached Mexico City, he learned that Óscar Romero, the country’s archbishop and most prominent spokesman for human rights, was shot in the heart as he celebrated Mass.

“Cuidence mucho los quiero mucho,” Ramirez wrote, the day he arrived in L.A. “Take care of yourselves I love you so much.”

Within five years, Ramirez’s mother had said goodbye to four sons.

The brothers sent home checks for $100. Other months, they explained that they needed to pay rent in their Echo Park apartment. Often, they told their parents how much they loved them.

Every time Maria Bertha Portillo de Ramirez received a letter, she would slit the envelope down the side and read it aloud to her husband, Juan Ramirez Hernandez. She was often the one who responded, crying over her lost sons.

“Thank God they’re alive,” Hernandez consoled her. “If they were here, they’d be dead.”

The quality of their lives had been deteriorating since the start of the civil war. The couple sold clothes in a market in El Tránsito, the small town near Usulutan where they lived. Often, the buses they took to San Salvador to buy wares would be forced to stop because of gun battles between guerrillas and soldiers. Portillo de Ramirez saw heads left scattered along the road.

In 1981, an explosion ripped apart the country’s most important bridge, the Puente de Oro, or Bridge of Gold. The blast severed a direct route to the eastern side of El Salvador and allowed guerrillas to gain a foothold there.

After that, living conditions worsened fast. Portillo de Ramirez and her husband knew they needed to leave their increasingly violent country. In 1985, they joined their sons in Los Angeles.

But within four months they returned home, unable to start over from scratch. Two years later, their youngest son followed.

Back home, guerrillas shot out a transformer in their town, leaving many without power or water for a month. The family piled bricks up against the garage door, hoping the barrier would protect them from bullets.

In the worst of the war, the three spent a night trapped in San Salvador. They hid in a walled-off staircase, listening to gunshots that rattled the windows. No one slept.

Today, decades later, Portillo de Ramirez uses a cane to get around the house where she raised her sons. It is bigger now thanks to money her boys sent home.

She keeps more than 200 letters — a testament to that terrible time — in dust-covered boxes that once held an iron and a digital alarm clock.

Among the 83-year-old’s possessions are Ramirez’s high school diploma and a copy of his application for a university scholarship. Months after he left for California, his family learned the financial aid had been approved.

Today, he lives in Los Angeles County, where he works in waste management. He could not attend the reunion because he fractured his foot.

But all those years ago, he left his dreams written in white paint on the back of his bedroom door: Dr. Juan José Ramirez.

Nov. 22, 1980

When the National Guard stopped the minivan he was riding in, Ricardo Alfredo Bermúdez prepared to die.

None of the six people in the car — including a cousin and an uncle — had documents on them. They’d given their passports to smugglers, because they needed to cross the border into Guatemala.

Six guards demanded the passengers tell them where their unit was. One hit Bermúdez in the chest with the butt of his assault rifle; another slammed his cousin in the ribs.

“No somos guerrilleros,” Bermúdez pleaded. “We’re not guerrillas.”

“If you don’t have documents, we’ll kill you,” the guard said.

Bermúdez was studying civil engineering when soldiers shut down the University of El Salvador in San Salvador. Now he and the others were trying to make it to the U.S.

The 20-year-old was quiet as the guards placed them in the back of a van. After just one block, the van pulled over and their captors demanded U.S. dollars to let them go. Bermúdez’s uncle paid $100 for their freedom.

It took Bermúdez 12 days to reach the U.S. border. He crossed into California in the trunk of a black van and headed to an aunt’s Hollywood apartment. That was his home for the next 10 years.

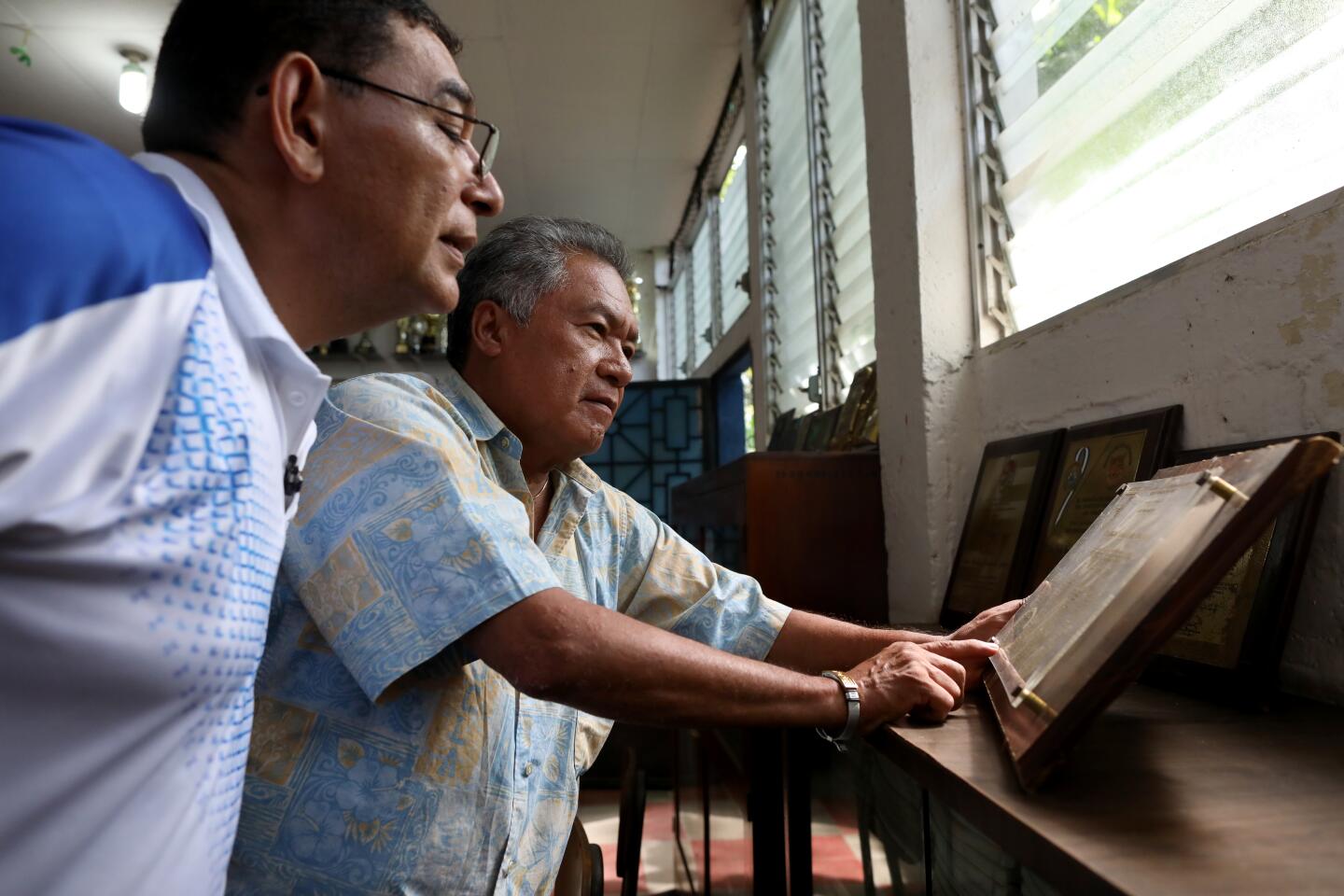

Four decades later, Bermúdez’s memory is still sharp as he recalls the feel of the gun in his chest and the fear of death. The North Hills resident is serious as he shares his past, but soon he’s laughing with his class once more.

November 2019

On a Friday night in Usulutan, in a fast food restaurant called Pollo Campero, the table of 12 was in a world of its own. The former classmates, nostalgic and happy, teased one another about past loves. They laughed so hard their bodies shook and tears streamed down their faces.

“Ay dios mio,” Ana Maria Vanegas said, as she looked at a picture from her 18th birthday in 1977.

“We’re just as beautiful as in the photo,” René Rafael Castillo Pozo replied, as he pulled her into a tight hug.

‘We’re just as beautiful as in the photo.’

— René Rafael Castillo Pozo

If felt as if they were students again, but in enthusiasm only. Their hair had thinned and turned gray. They wore reading glasses and complained of lung issues. One of them hurt his back from all the horsing around.

Montecino’s husband wouldn’t let her come to the 25-year reunion. (Their divorce freed her to attend this one). She had stayed in Usulutan for years, washing her clothes and bathing in the river when the fighting knocked the power out for weeks. A friend was killed during a shootout between guerrillas and soldiers.

Bodies were left dumped with their thumbs tied behind their backs.

“There wasn’t a day without death,” recalled Montecino, who is now a teacher. “So many innocent people.”

Arce’s classmates nicknamed him Juan Wright, after one of the country’s millionaires in the late 1970s. Because Arce had crossed illegally into the U.S. during the war, he wasn’t able to return to see his father before the elderly man died. Now a U.S. citizen, Arce owns a trucking company in L.A. and employs nearly 100 people. He picked up the tab for dinner.

The classmates spent the weekend together, reuniting for Mass at the same church they had visited on graduation day. Nearly 40 of them filled the pews, sweating because they were unaccustomed to the blowtorch-like heat. The priest congratulated the class of 1978.

“I was a year old,” the young priest said, prompting groans from the 59-year-olds. “How the years have passed.”

On their last day together, on a Sunday, they lay in rainbow-colored hammocks at Playa El Espino, drank from coconuts and cooled down with minutas, shaved ice desserts in Styrofoam cups. During the civil war, guerrillas had occupied the beach.

Now, the former students drank Golden beer and blasted La Sonora Dinamita, the music drowning out the crashing waves. Two best friends gossiped about their lives. Others talked about children pursuing master’s and doctorates and showed pictures of their grandkids.

A man and woman walked along the gray sand, searching for seashells. They were a couple once, a lifetime ago. Today, one is married to someone else. They made a pact on that sweet afternoon: If either of them was in a wheelchair at the next reunion, the other would push it.

As the sun dipped into the ocean, five men kicked a soccer ball across the sand. They fumbled tricks and formed a tight circle to keep from running more than was needed.

Vanegas, who lives in the San Fernando Valley, sat on a nearby bench, laughing as she watched her former classmates play.

“Recordar es volver a vivir,” she said.

To remember is to live again.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.