California is still stuck in the past on medical malpractice payouts

SACRAMENTO â California is arguably the nationâs most politically âprogressiveâ state. Thatâs our reputation. Left coast and all that. But on one issue, no state is more regressive.

Weâre extremely backward on allowing reasonable jury awards for victims of severe medical malpractice.

Itâs looking like thereâll be a fiercely fought ballot initiative next November to bring Californiaâs malpractice payouts into the 21st century.

More on that later. First some background:

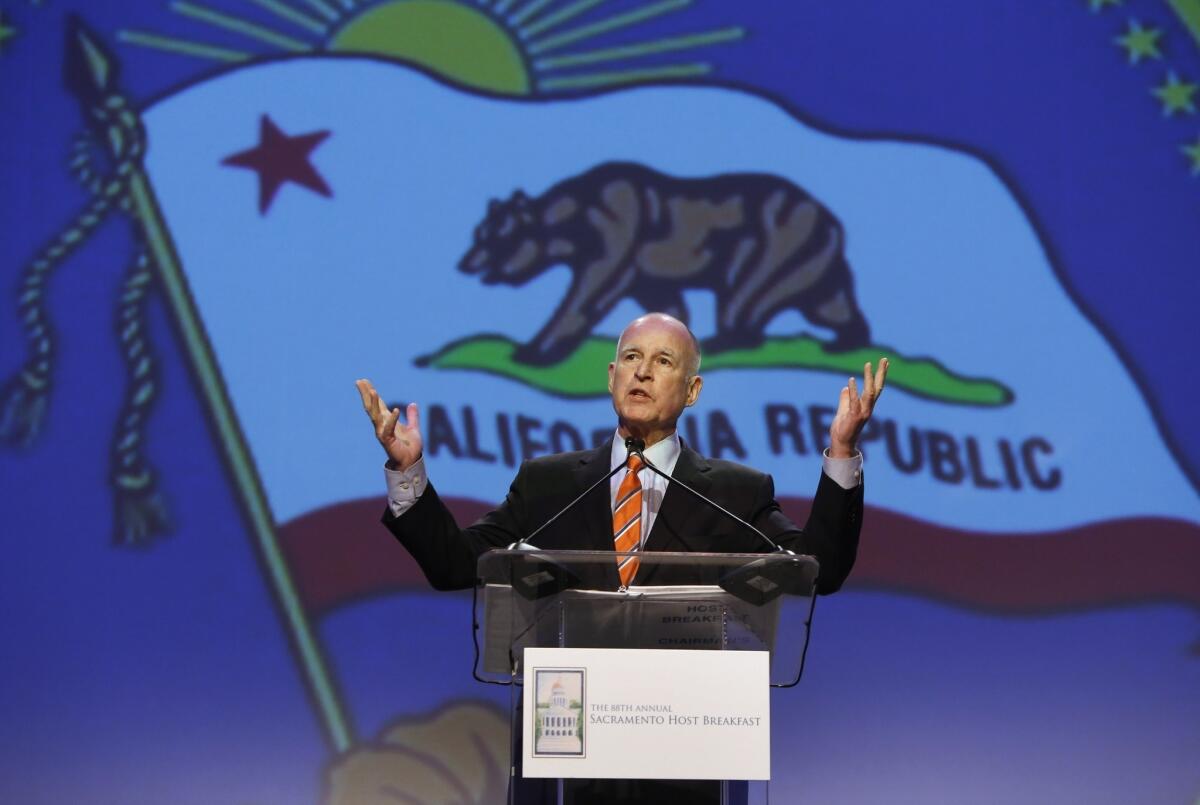

About 45 years ago, in 1975, new Gov. Jerry Brown and the Democrat-controlled Legislature overreacted to threats of doctors retiring or fleeing the state because malpractice awards were rising and insurance premiums climbing even faster.

The medical profession and insurers sponsored legislation to cap âpain and sufferingâ awards at $250,000. The measure passed and Brown signed it.

Lose a leg, lose two legs, lose a spouse or child to botched medical care and it was worth a max $250,000. Thatâs still the law.

Never mind what you might see in a movie about a colossal award in another state. In California, after paying attorney fees and court costs, youâd be fortunate to net $100,000. And youâd probably settle for less to avoid court expenses and frustration, if you could even find an attorney to take the low-paying case.

A victim could still collect for actual economic losses, such as healthcare expenses and lost income. But if a child, stay-at-home mom or retiree was permanently crippled or died, they didnât have wages to lose. So they or their survivors were basically limited to $250,000 for pain and suffering.

Moreover, the cap wasnât indexed to rise with inflation. In 1975 dollars, $250,000 is only about $51,000. If the cap had been indexed, it would be worth $1.2 million today.

The reason it wasnât indexed is typical cynical politics. The billâs Democratic author offered an amendment to annually adjust the cap for inflation. But the lawyer lobby aligned with the medical cabal to oppose the indexing.

Why? The lawyers figured that making a bad bill better would improve its chances of being passed and signed. Bad figuring. It was enacted anyway.

In 1987, the cap was reaffirmed by the Legislature and tweaked to benefit attorneys, but not victims.

There had been a threat by reformers to sponsor a ballot measure repealing the law. Product liability was a big issue in the Capitol. Legislative leaders and special interests responded with a legendary ânapkin dealâ at Frank Fatâs, a venerable Chinese restaurant and political watering hole.

Lobbyists for trial lawyers, medical providers, insurers, business and tobacco inked a five-year peace pact on a linen napkin.

One provision allowed for indexing lawyersâ fees in malpractice suits, but not victimsâ awards. The rationalization was that this would entice more attorneys to take these cases. It didnât much.

In 1993, while out of office, Brown fessed up that heâd concluded the 1975 law was a horrible mistake. In a letter to consumer activist Ralph Nader, Brown âstronglyâ opposed adopting a California-style malpractice award cap for the nation.

California, Brown wrote, had âfound that insurance company avarice, not utilization of the legal system by injured consumers, was responsible for excessive premiums.â

âSaddest of all,â he continued, the act âhas revealed itself to have an arbitrary and cruel effect upon the victims of malpractice. It has not lowered healthcare costs, only enriched insurers and placed negligent or incompetent physicians outside the reach of judicial accountability.â

But when Brown was elected governor again, he didnât do anything about it. The governor didnât take a position on a 2014 ballot initiative to raise the pain and suffering cap to $1.1 million, adjusted for inflation.

In truth, that measure tried to do too much. It was muddied up by a requirement that hospital doctors submit to drug testing. Proposition 46 failed miserably, 67% to 33%.

The medical industry spent nearly $60 million convincing voters the measure would drive up healthcare costs and enrich trial lawyers. Healthcare costs, of course, have gone through the roof anyway. And good trial attorneys can get rich without pursuing medical malpractice suits.

The new reform attempt would raise the cap to $1.2 million and adjust it annually for inflation. But it also would do much more. It would completely remove the cap in cases of âcatastrophic injury,â meaning permanent physical impairment, disfigurement, disability or death. In other words, lots of cases.

For perspective, 20 states have no caps; 32 either have no caps or exempt catastrophic injuries and death. California is one of only three states with a cap as low as $250,000 and no exemptions. The two others are Montana and Texas.

Sponsoring the new initiative are the activist group Consumer Watchdog and wealthy trial attorney Nick Rowley, who is paying for the collection of 623,000 voter signatures. He plans to personally put up $10 million and raise another $30 million. But he expects a $100-million opposition campaign.

âIâve had to look hundreds of people in the eye,â Rowley says, âand tell them, âSorry. In California your constitutional rights are limited. You donât really get a jury trial. Itâs a lie.ââ

Consumer Watchdog President Jamie Court brought several malpractice victims to Fatâs last week to kick off the initiative signature gathering.

Former U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer spoke, asserting that raising the limit on pain and suffering awards would help deter medical malpractice.

Court ended the Fatâs session by symbolically tearing a napkin in half.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.