The unusual work environment that helped Naughty Dog make the hot game ‘Uncharted 4’

- Share via

Co-presidents. Co-directors. Co-animation leads. Co-art directors.

At Santa Monica video game maker Naughty Dog, it doesn’t take long to notice that co-responsibilities are commonplace. Pitting bosses against each other to decide on characters, gameplay and script is a key strategy the firm credits for its succession of highly-rated games.

The latest, “Uncharted 4: A Thief's End,” topped the charts in several countries with 2.7 million copies sold worldwide during its first week on the market this month. The $60 Sony Playstation 4 exclusive culminates Naughty Dog's series featuring fictional treasure hunter Nathan Drake. It's like a "playable summer blockbuster" movie, in the company's words.

Naughty Dog has long cultivated an unusually free-flowing development process that empowers anyone at any stage to share their ideas -- and defend them. Its dogmatic emphasis on uniting story designers and technology makers is the sort of multidisciplinary collaboration that's all the buzz at business schools and entrepreneurship seminars.

Some may dismiss the system as unreplicable in a company with thousands of employees and dozens of projects, compared with the 200 workers at Naughty Dog focused on one game. But Naughty Dog Co-President Evan Wells insists it can scale, offering the “Uncharted 4” journey as a potential playbook.

“If you get a single person having too much authority, you get surrounded by yes-men or not enough people challenging you,” Wells said. “You’re going to get better results when you have more challenges to an idea.”

Richard Lemarchand, who retired from Naughty Dog in 2012 and became an associate professor in the USC Games program, said Naughty Dog's “magic” emanates from the mind-meld of technical and creative workers.

Naughty Dog’s structure dates to its founding in 1984, when technology was simple enough for two people alone to create a stellar game. In Naughty Dog’s case, Jason Rubin led design for games such as "Crash Bandicoot" and Andy Gavin handled software programming. They chose Wells to take over a decade ago, but he immediately made an equal out of Christophe Balestra, a tech guru.

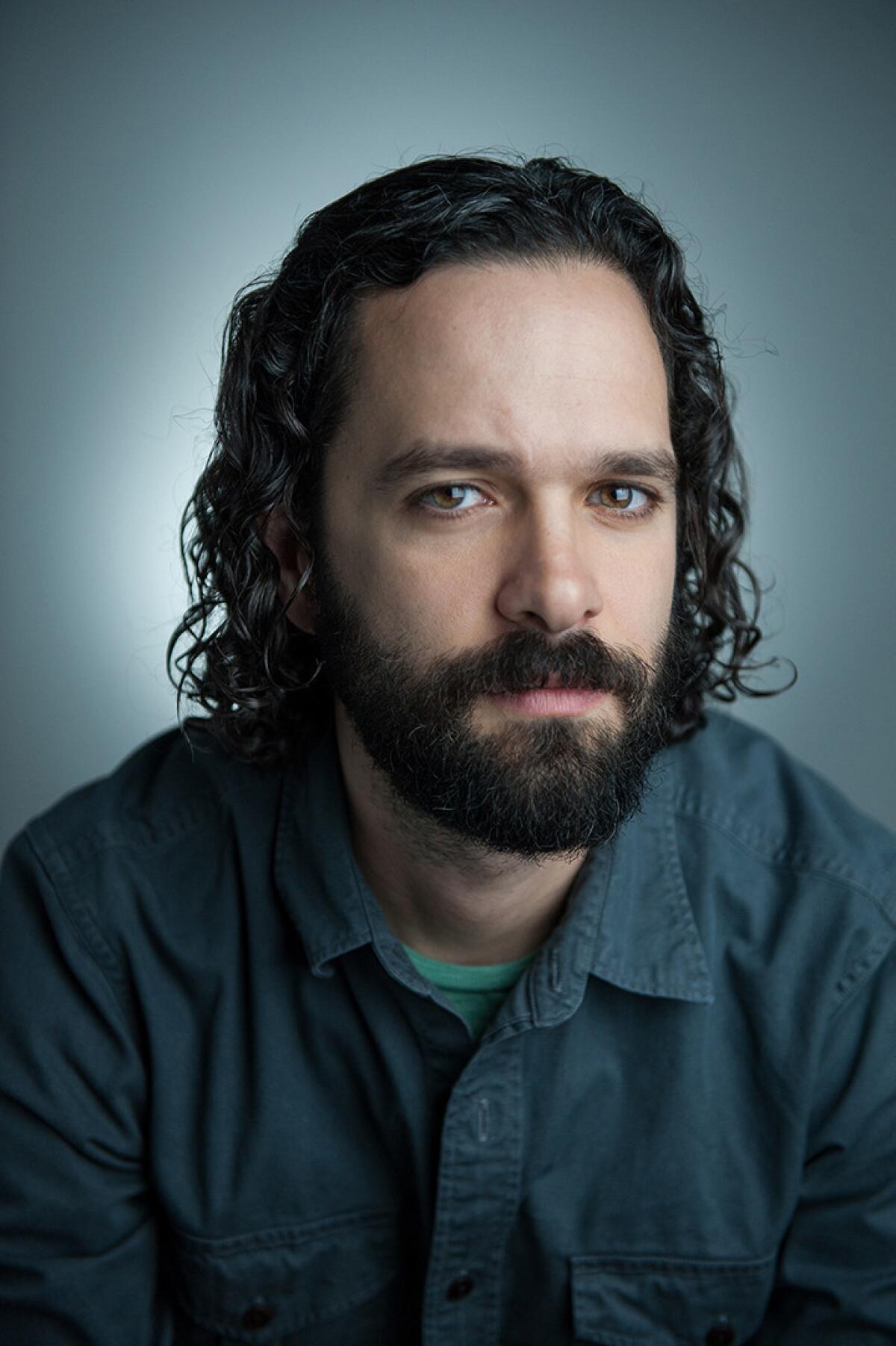

For the latest "Uncharted," the co-presidents delegated day-to-day gamemaking duties to another pair, storymaster Neil Druckmann and technology overseer Bruce Straley.

The company, which is a unit of Sony Interactive Entertainment America, didn't produce a complete script from the beginning. Druckmann’s teams offer a core idea -- “obsession” is the one for “Uncharted 4” -- that guides decisions.

Naughty Dog wanted to explore whether its adrenaline-fueled protagonist Drake could really give up adventure to settle down with his family. Is there any way he could preserve some of that treasure-seeking impulse? What, if anything, could tip him away from family?

Those questions inspired ideas for characters, locations and gameplay elements. The story designers scribbled the plot points on index cards arranged on a cork board. The idea was to have a foundation, but one that commanded less attachment than a hulking script book, Druckmann said.

For the action-adventure shooter “Uncharted 4,” discussion included having wide-open terrains that gave players more choice. They wanted smarter enemies that could slow Drake. They also sought to highlight nuanced movements and facial expressions that could convey ideas without dialogue.

Artists translate the index cards into sketches. An “Uncharted 4" drawing showed a strong emotional bond between Drake and his brother -- inspiring Druckmann to better incorporate the relationship in the index-card script.

Step by step, the informal chatter and emails evolved into specific jobs on Tasker, an internally developed duty-management app.

Druckmann shrugs his shoulders at new hires who try to author comprehensive memos detailing far-off plot points and issues.

“Oh, they’ll learn,” he says. “Documentation can become stale very quickly.”

That belief means Naughty Dog doesn’t lean on producers for organization. Many game companies have a producer for every 10 developers, Wells said. They call meetings and centralize planning, acting as guardians of developers' precious time.

Wells wants everyone to track their own responsibilities.

“Producers become a crutch, where it’s someone else’s job to make that communication,” he said. “We want people to get out of their chair and get the help they need immediately."

Though producers might prevent the frustration caused when some people are left out of conversations, Naughty Dog has found that the speed gained from not having those middle managers more than makes up for it.

“Even if you’re off course by 45 degrees, you’re still moving faster forward than if you’re constantly bogging everybody down and affecting their workflow,” Wells said.

Perhaps the closest thing to a master document beyond the index cards is a 90-minute video of a Powerpoint presentation Straley and Druckmann gave to the company when pitching the project. New employees are instructed to watch the video to get up to speed.

Many game companies leave the writing until after the gameplay is built, but writers and developers get started at the same time at Naughty Dog. Rhianna Pratchett, lead writer for “Tomb Raider” games, said calling in writers too late turns them into “narrative paramedics.”

Naughty Dog pays a premium to keep writers in-house and working from day one. But Wells says they achieve a better harmony with the graphics because they play the game and constantly fine tune the story.

The same goes for actors, whose motions and voices are used in the game. They record, play the game and re-record. They’ll do dozens of takes to marry the tone with the action, coming to fiercely embody their characters.

Again, the setup increases costs -- but Naughty Dog has home-field advantage. Game companies outside the region usually have only a couple of weeks in Los Angeles for filming. “Uncharted 4” took two years to film, with actors in the studio no fewer than five days a month, Wells said.

Straley and Druckmann have adjoining desks. They overhear what the other is working on, and talk to each other to resolve any story versus gameplay conflicts before undertaking work on major scenes.

But Druckmann locks himself up in a conference room from time to time to crank out scripts, or he's stuck on a motion-capture set. Because they don’t schedule formal meetings or centralize planning, a week of separation can cause divergent actions.

One mismatch in “Uncharted 4” involved a scene where Drake is sneaking into new territory. Druckmann had anticipated Drake being unchallenged. Straley’s team had guards.

They got into a heated discussion: Can the story shift? What will it affect? A solitary experience made most sense, so they removed the guards. That required redoing art and code, wasting three weeks of part-time work for three people. They bit the cost.

Another mix-up came when actors in one scene were oriented in the opposite direction of what software programmers had anticipated. Naughty Dog was willing to reshoot, but video editing software managed to flip the scene without too much disturbance.

Testing every inch of the game also leads to adjustments. A scene where Drake walks through a crowded gala didn’t teach players anything new about Drake’s character, Druckmann told Straley. So Straley's team added a new challenge for players: Drake, to prove to his brother his tough-guy bonafides, decides to try to pickpocket a passerby faster than his brother can.

Allowing back and forth between teams and avoiding strong-armed planning isn't without downsides. Emmett Shear, chief executive of video app Twitch Inc., told employees in a corporate values memo publicized Tuesday that though "the enemy of speed is coordination," the flip side is that "the enemy of good decision making is ignorance ... of the knowledge of others."

Costs can get out of hand. Mistakes can crush a product. The way to get around that is to establish a "shared vision of the future," with individuals instructed to find the fastest way there, Shear wrote.

A similar philosophy has enabled Naughty Dog to deter major bottlenecks or rifts between departments. Rivals have taken notice: Microsoft Xbox division chief Phil Spencer in 2014 called the studio's operations worthy of study because of an "amazing track record."

Naughty Dog releases fewer games -- six over the last decade -- than most competitors. But they get almost universal support from critics, and sell well, with the "Uncharted" series approaching 30 million copies sold. Only a small cadre of gamemakers, including former Microsoft studio Bungie, have enjoyed similar streaks.

"It's the culture where you put ego aside and come back to a succinct vision of what we’re trying to achieve," Wells said. "Everyone gets that core message, and that’s unique."

Twitter: @peard33