Workers ‘can still win really big.’ How labor can demand more

- Share via

Longtime labor organizer Jane McAlevey has some advice for what workers should demand of employers and union leaders: Don’t sign gag orders and commit to transparency.

That’s what McAlevey, the author of several books on union organizing and negotiating contracts, recently told a room of union staff and members at the United Food and Commercial Workers union Local 770’s home base in downtown Los Angeles. She was discussing her new book, “Rules to Win By: Power and Participation in Union Negotiations,” published in March, just in time for L.A.’s summer of strikes.

A strike in March by bus drivers, custodians, special education assistants and other low-paid workers at Los Angeles Unified School District set the tone for the rest of 2023, and since then, it’s been a busy and “hella exciting” time for labor in Southern California, said McAlevey, a senior policy fellow at the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

But broadly there are still obstacles to workers securing major wins, McAlevey said. Namely, unions’ practice of using small committees of worker representatives to negotiate labor contracts behind closed doors.

In the book, McAlevey and her coauthor, Seattle labor lawyer Abby Lawlor, try to demonstrate a more transparent model by dissecting case studies — Boston hotel workers, educators in New Jersey, nurses in rural Massachusetts and Philadelphia, journalists from the Los Angeles Times and Law360, and hospital workers in Germany.

As Labor Day rolls by during a momentous surge in worker organizing, here are some lessons on building a strong contract campaign, according to McAlevey. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Los Angeles is sitting at the vanguard of two trends: increasingly expensive housing and an increasing amount of cross-union solidarity.

Was there a specific moment that served as inspiration for this book?

This book is a direct credit to the German labor movement. A group of organizers at German trade unions asked me to keynote as a conference about building a strike. Most people think of Germany as like, the Shangri La of worker rights. It’s not. In 2019, union busting in the style we see in the U.S. was hitting Germany. I got very busy doing training work over there because employers’ tactical warfare was adapting.

The organizers kept asking questions about how I negotiate — which is so foreign for them because in Germany, one big guy goes in and negotiates for a whole sector. They said, “We need to learn how to do this. We need a manual from you.” They did not give up. Every few weeks I got a long email saying “are you going to write the book on negotiations?”

The 20 elements of open negotiations I list at the beginning were a response to some wicked good peer reviewers. The feedback was super consistent, like “McAlevey shows us these great case studies but she never actually tells us like what are the things.”

What do you see as the three main takeaways from your book?

The first is that workers actually can still win really big. I don’t want to settle for less-than-good contracts. Workers have, for 50 years, been taking it in the neck in this country; we see it in the inequality divide. It’s just a function of greed. There is plenty of money. So the first lesson is, workers actually can win much more, but it’s a question of power and strategy.

Secondly, it is about showing — not talking about showing — what new democracy looks like. That’s really important to me. There are plenty of unions that are not exactly good at being ‘small d’ democratic — at involving all the members in negotiations.

The hotel strike is hitting consumers harder than any other during Los Angeles’ labor summer, bringing complaints, a disrupted wedding and violence.

You have to build guardrails to protect democracy. Forcing all unions to have to allow the members into negotiations is an example of one. That way, no deals can get cut behind workers’ backs; nothing’s going to happen that the workers themselves aren’t directly involved in.

The third one is about the question of political education and governing power and teaching workers what it means. When do you have enough power to set the rules? What are the rules that you want set? How do you build unity and solidarity around them?

What is the main obstacle to the labor movement in Los Angeles, California and beyond?

The governing paradigm.

There’s a certain dynamic and logic happening during an organizing campaign where the energy is all one way: It’s about staying united, overcoming union busting, warding off division, building solidarity. But at the end of a hard-fought National Labor Relations Board election, there usually is real division. Even if there isn’t — which is rare — but even if there isn’t, the transition to “how do we negotiate our contract” is a really big transition for people.

What the tradition I come from argues is, since negotiation is all about power, the person that you have leading the table is an organizer who actually understands how to build worker power.

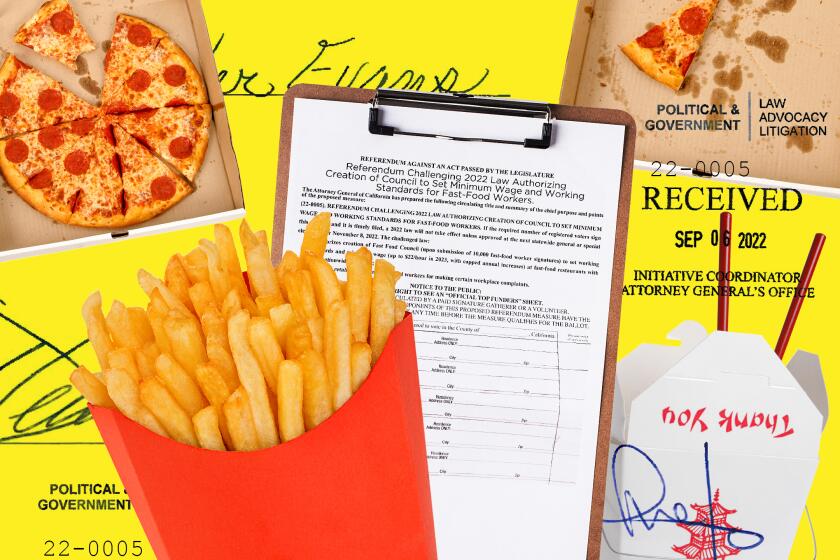

California voters complain that canvassers for a measure to repeal a law expanding protections for fast-food workers lied about the effects.

Think about how much power is required to force lawmakers to take action, whether it’s on fast-food issues or taxing the wealthy in California. You look at the control of Democrats in California, and you realize how many problems should be solved that we’re not solving: that’s because of the architecture of power.

It’s super rare in the labor movement for organizers to be the negotiators. Negotiators are usually lawyers. This book is basically an organizer’s approach to negotiations.

During your July book event in L.A. you said the most basic value union leaders need to commit to is transparency. What are a few simple steps to take relating to transparency?

There are a lot of unions for whom a simple demand for transparency seems impossible. That is not a democratic practice, in my opinion.

There are a lot of unions that are crushing expectations — putting downward pressure on the idea of what you should expect to win. It’s kind of common, and that’s frightening.

Not signing gag orders would actually be a very big leap for a lot of unions and would be a great first step.

How can transparent negotiations help to resolve conflict within a bargaining unit? How can it help to enforce a contract once it’s in place?

In hospitals, where I’ve done a lot of my negotiations, there’s persistent tension. Emergency department nurses might think they belong in the highest tier of the wage scale alongside the intensive care unit nurses because sometimes they’ve got critical patients coming in. Then people in the ICU might disagree.

Where do you belong on the wage scale? Do you take into account seniority? There’s so many fundamental questions that we can divide ourselves over. Learning to govern is part of the beauty of negotiations.

For me, it’s what workers are doing away from the employer — not away from the table, but away from the employer — learning how to write the best rules possible to govern their workplace, and then learning that it takes real power to enforce it.

My approach to everything is, put it out to people. Don’t hide it; surface the tension. Work through them as a group or break people out into small discussion groups.

I do weekly meetings for months leading up to the start of contract negotiations. In theory, tensions have had months to work themselves out before bargaining begins. So it’s not exploding right at the last minute, and people go to the table united and together on compromises that they learned to make.

Column: It’s a happy Labor Day indeed after NLRB cracks down on employer sabotage of union elections

After nearly 30 years, the National Labor Relations Board restores a policy that truly punishes employers for unfair labor practices.

When they’re fighting the fight, I always say, “Look, do you want the boss to make the decision for you? Or do you want to make the decision? Do you want to let him keep dictating the terms and conditions or do you actually want to figure out a way for us to resolve this conflict ourselves?” And that’s foundational.

Then you do that unusual thing I write about in the book, which is a ratification vote on the contract proposals. That’s the final way to just say, “All right, everyone agrees, these are proposals that are going in.” That avoids so much disappointment and conflict that I see with people who don’t use that approach, or who don’t tell the workers what they’re negotiating, don’t tell them what’s going on in the room. That’s when you get a lot of really upset people.

Enforcing your contract is best done when every single worker has been involved in the negotiations because workers then understand what the contract language means. They understand it takes power to enforce it, not lawyers. Having a good lawyer in the background is good, but if you only file grievances and you become a grievance mill union, you’re gonna go down, you’re going to weaken, you’re going to atrophy.

You have called out issues with the way United Auto Workers leaders ran their contract campaign for University of California academic workers. Can you explain your thoughts on what went wrong?

(Note: In a piece McAlevey wrote last year she said the union failed to effectively bring together various moving parts: There were four separate units in negotiations, including academic student employees, graduate student instructors, postdoctoral scholars and academic researchers — overseen by three separate union locals.)

I objected to much of how the contract campaign was run. Yeah, I don’t think they did a good job on this at all. It was a pretty badly run affair. I wrote about it a little bit in the Nation. Not a lot. It was during our strike, so I was trying to be gentle. But I was indirectly, quite seriously calling out some of what had been happening.

The union did all this work to line up the contracts so that they expired at the same time. But then the UAW position holders, as I call them — not leaders — did a lot wrong: they kept all the workers divided, and it set up huge tensions.

The mistake that they made from the beginning was allowing the boss to keep the different units at separate negotiating tables.

Just watching it was amazing. They were like breaking almost every rule. They settled academic researchers contract before the others expecting us to then cross the picket line of our graduate students.

UAW will say that they were practicing open negotiations because anyone could join the Zoom meetings. But it’s not really open negotiations if you’re having a secret off the record with the employer every week, which in fact, they were doing. So you can put on a show and look like you’re doing your democracy, or you can actually really do a democracy.

But I don’t want to talk about things that went badly. I actually want to constantly show workers what’s possible, how to win, what works and what you can do to actually win. That is my life mission.

I’m not interested in writing about failure. It’s all around us. I think what workers need is direction, clarity and some alternate ideas.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.