Column: A Teamsters strike against UPS could remake the union movement for the better

Over the last year, unionization drives by Starbucks baristas and Amazon warehouse workers have all but monopolized the attention of the labor organizing world.

That may be why the most important development in the field has operated under the radar until very recently. Weâre talking about the contract talks between United Parcel Service and about 340,000 members of the Teamsters union.

The negotiations have already yielded an overwhelming vote by the members to strike if no deal is reached by July 31, when the current contract expires. Hand-wringing about the impact of a UPS strike has intensified lately, since the shutdown of a company that handles an estimated 6% of the nationâs gross domestic product (according to UPS) could have dire economic consequences.

Sean OâBrien has made it clear that we are not going to take any concessions.

— Viviana Gonzalez, Teamster steward

Whatâs more important, however, is the impact that a successful negotiation or a strike could have on the health of American organized labor.

It would demonstrate that workers have truly gained leverage over employers after three pandemic years and a year of inflation fueled by corporate profiteering. It could also demonstrate the value of union solidarity in the face of determined resistance by employers.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As Iâve reported before, the notion that American workers have gained an edge over employers in the pandemicâs wake has been wildly overstated.

Labor expert Theresa Ghilarducci of the New School points us to a recent survey by Oxfam showing that among the 38 developed nations in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. ranked at or near the bottom on measures of wage policies including minimum wages (36 out of 38), rights to organize (32nd) and worker protections (dead last at 38).

Employers have fared much better, thank you. That includes UPS, where the pandemic burnished the financial picture. UPS revenue grew to $100.3 billion last year from $74.1 billion in 2019, and profit grew to $11.6 billion from $4.5 billion in 2019.

In other words, the companyâs profit margin nearly doubled, to 11.6% last year from 6% in the year before COVID. If thereâs an argument against distributing more of that largesse to the workforce that made that growth possible, letâs hear it.

Given U.S. law and past practice, piecemeal organizing drives in discrete workplaces such as Starbucks stores always face an uphill battle.

Even Federal Reserve economists know that wages had no effect on inflation. But that doesnât stop Fed Chair Jerome H. Powell from harping on labor costs and ignoring the real culprits.

Starbucks has managed to fight many of its barista unionization efforts to a draw by exploiting the indifferent and time-consuming system of labor law enforcement in the U.S. The coffeehouse company has engaged in what a National Labor Relations Board judge found in March to be âhundreds of unfair labor practices,â but his ruling came more than a year and a half after the offenses were committed; the enforcement process still hasnât concluded.

The Teamsters canât be manipulated as easily, since the union is bargaining for its entire UPS membership, companywide. That said, previous Teamster leaders have been overly indulgent toward the company; some of their historical concessions are on the negotiation table right now. Todayâs Teamster leadership, moreover, won their seats by promising specifically to take a hard line with UPS.

That stance has already yielded accords on numerous noneconomic issues. The most important may be the companyâs agreement to install heat shields and air conditioning in its delivery vehicles, in which summertime temperatures can soar higher than 100 degrees; scores of UPS drivers have reportedly succumbed to heat-related injuries.

Last summer, driver Esteban Chavez Jr. died from what his family maintains was heat stroke suffered while delivering packages in Pasadena. (The question, of course, is why it took union negotiations for UPS to address this issue.)

âWe have a new person in charge,â says Viviana Gonzalez, a UPS driver for nine years and a steward for Covina-based Teamsters Local 396. Sheâs referring to General President Sean OâBrien, a former UPS employee who won his Teamsters post in 2021 by defeating a candidate handpicked by former President James P. Hoffa.

âSean OâBrien has made it clear that we are not going to take any concessions,â Gonzalez told me. She says the workforce takes pride in having kept UPS operating through the pandemic â âwithout us, you didnât get food, medicine, essential stuffâ â but sentiment is widespread that the company hasnât sufficiently acknowledged the workersâ role during that difficult period.

The most interesting aspect of the current contract negotiations may be the unionâs demand to eliminate a lower, second tier of drivers who do the same work as other drivers but for lower pay. The main difference in their duties is that they work Tuesday through Saturday, rather than weekdays.

The moral scourge of child labor was supposedly eradicated in America more than 100 years ago. Red states are bringing it back in the name of parental rights.

Creating the so-called 22.4 drivers (named for the contract section that covers them) allowed the company to extend delivery services into the weekend without paying the full-time workforce extra for weekend duty or overtime.

Full-time drivers earn an average of about $95,000. The 22.4 drivers earn less per hour while receiving comparable health and pension benefits.

Earlier contracts gave the company more flexibility to hire part-time workers, to the point where about half of all the Teamster members at UPS are part-timers. The company says a part-time workforce is âessential to our success,â because the average workday encompasses âalternating bursts of activity and slack time.â

UPS also portrays part-time opportunities as âideal for many peopleâ who want time to âadvance their education and pursue their passions.â

That sounds a lot like the argument by gig firms such as Uber and Lyft, which assert that classifying their drivers as independent contractors affords them the âflexibilityâ they value in their lives, even if it means giving up the job protections and benefits that come from classification as âemployees.â For the companies, it means lower costs, so you be the judge.

At UPS, the part-timers earn less than half the average hourly wage that full-timers receive.

Serious labor leaders know that two-tier and part-time employment is poison for workersâ interests. Managements have long âassumed that full-timers wouldnât fight for more full-time opportunities and better pay for part-time workers, while the younger part-time work force wouldnât fight for better pensions or reduced subcontracting of full-time jobs,â Teamster officials Matt Witt and Rand Wilson observed in a 1999 retrospective about the last UPS strike, in 1997.

That two-week strike ended with one of the best contracts the Teamsters ever achieved with UPS. After a string of mediocre contracts signed by union leaderships racked with internal dissension, the union in 1997 took a more militant stance toward UPS and, perhaps more important, leadership made a concerted effort to engage members in the contract negotiating campaign.

The issues then, as now, included the companyâs reliance on part-timers â who often worked as many hours as full-timers, but were paid less. During the four years preceding the 1997 contract talks, more than 80% of new hires were classified as part-time. The striking workers benefited from their positive public image, which immunized them from a company advertising campaign aimed at portraying them as greedy.

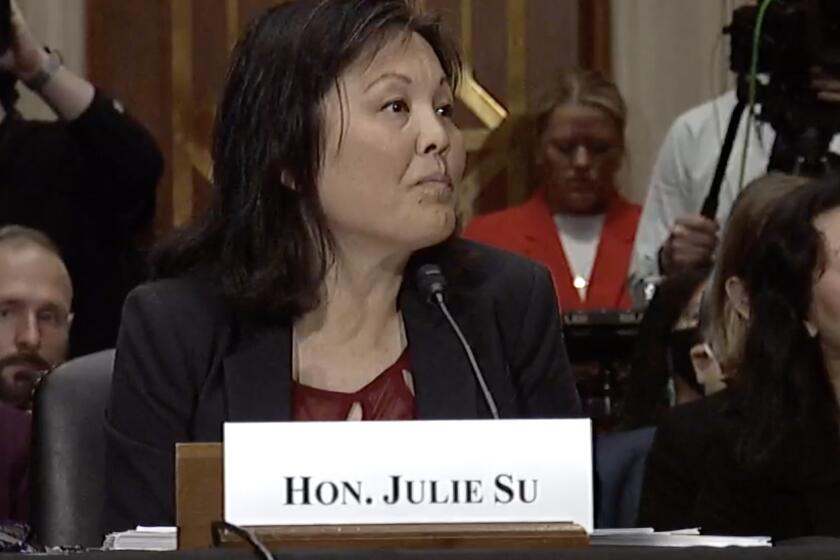

Julie Suâs accomplishments make her a spectacularly qualified nominee for Labor secretary. Thatâs exactly why Republicans â and some Democrats â will do their best to block her confirmation.

The strikeâs success bore lessons for organized labor generally, chiefly that successful bargaining was the best advertisement for union membership. âYou could make a million house calls, run a thousand television commercials, stage a hundred strawberry rallies, and still not come close to doing what the UPS strike did for organizing,â AFL-CIO President John Sweeney told the umbrella unionâs national convention a month later.

As it happens, however, the glow faded. Organized labor continued its steady decline in membership and influence. At UPS, the Teamsters allowed the company to implement the 22.4 classification in 2018, even though 54% of the voting membership rejected the contract.

Then-President Hoffa ruled the contract to have been ratified, citing a union rule that permitted him to do so if voting turnout had dipped below 50% or the ânoâ votes didnât exceed two-thirds. Turnout had been only 44%.

The strike vote doesnât mean that a walkout is inevitable, obviously. But the vote is a signal that UPS management ignores at its peril. The most important question may be on which side of the scale the Biden administration places its thumb.

In November, when railroad managements balked at union contract proposals calling for more sick days â proposals the financially flush railroads were well able to afford, thanks to record profits â Biden sided with the railroads. Then, as now, the rhetoric was all about the âcripplingâ effects of a strike.

Biden has been portraying himself as a pro-labor president. The truth is that he has been a better friend to labor than any of his predecessors since Franklin D. Roosevelt. That makes the UPS situation a test he canât afford to lose. He should celebrate the Teamstersâ solidarity in demanding a fair share of UPS profits. Make no mistake: If thereâs a strike, it will be because UPS management wanted it to happen.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.