Column: Can sanctions stop Russia? History says it will take time

- Share via

Russia is on the verge of becoming a pariah state. With its attack on Ukraine, it faces a future of diplomatic isolation, economic devastation and nearly universal moral condemnation.

The question now is whether ostracizing Russia through sanctions will force it to change direction, shut down Vladimir Putin’s empire-building ambitions and end the invasion of Ukraine. History says that sanctions may work, but warns that they may not work quickly.

Experts point to the sanctions imposed on Russia after its invasion of Ukraine in 2014. These were “designed to punish high-level government officials and weaken the Russian economy through restrictions on trade and finance with Russian energy companies and specified banks, in the hope that these measures would deter further military advances in Ukraine and neighboring countries,” trade and sanctions expert Jeffrey J. Schott of the Peterson Institute for International Economics observed earlier this month, when Putin’s intentions were still murky.

Russia is a unique case: It’s larger and more economically integrated with its neighbors than any previous sanctions target.

“The sanctions had only a minor economic impact on the Russian economy, did little to dislodge Russia from Crimea and eastern Ukraine, and — as now seems evident — only temporarily deterred Putin’s territorial ambitions,” Schott wrote.

The sanctions facing Russia in the aftermath of its latest attack are more stringent, and may have a more pronounced impact on the Russian economy and on the personal fortunes of Putin and his inner circle.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Indeed, Schott wrote that further constraints on Putin and his cronies — say placing them on the U.S. Treasury’s list of specially designated nationals subject to asset seizures and travel restrictions — “would ostracize Russia further as a pariah state,” even if those individuals have been nimble enough to place their assets beyond the reach of government seizures.

President Biden alluded to that in announcing sanctions at the White House on Thursday, which include “targeting Russian elites and their family members,” cutting them off from the U.S. financial system, freezing assets they hold in the United States and blocking their travel to the United States.

Biden also announced the severing of at least five leading Russian financial institutions from the U.S. financial system and cutting off financing from 13 Russian government-owned enterprises. He placed stringent restrictions on Russia’s import of “technological goods critical to a diversified economy and Putin’s ability to project power.”

They follow earlier sanctions imposed in response to Russia’s first moves into Ukraine. Those sanctions were squarely directed at economic factors. They included Germany suspending certification of the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline, a completed $11-billion Baltic Sea pipeline from Russia to northern Germany.

Isolation and the effects of economic sanctions have been known to bring about political change in pariah or rogue states in the past. But Russia is a unique case: It’s larger and more economically integrated with its neighbors than any previous sanctions target.

The term “pariah state” itself is ill-defined — it’s not a formalized term in geopolitics. Traditionally, however, it’s been applied to smaller countries already on the outs with the international community for reasons such as human rights violations or sponsorship of terrorism.

As trade and sanctions expert Robert E. Harkavy defined it many years ago, “the pariah state is a small power with only marginal and tenuous control over its own fate ... and lacking dependable big-power support.”

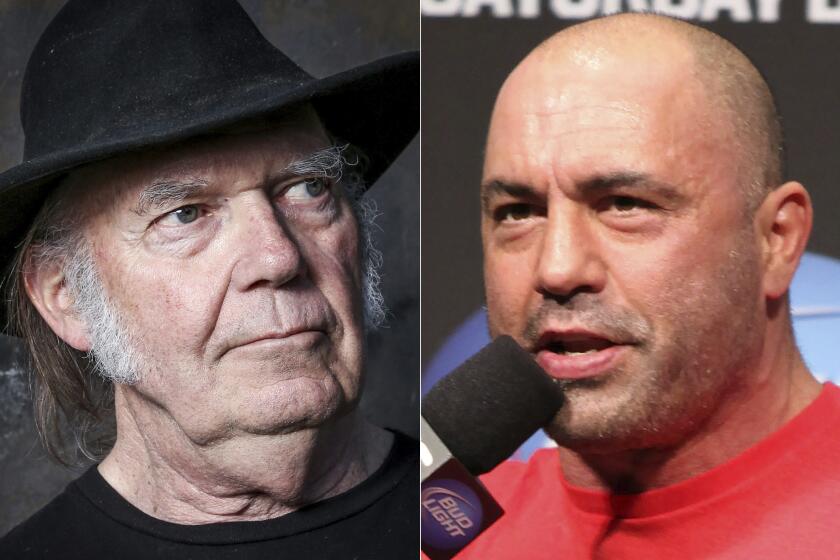

Neil Young did society a big favor by targeting Joe Rogan’s COVID lies.

That would apply to several, though not all, of the dozen or so states most commonly treated as pariahs, including Belarus, Myanmar, Eritrea and North Korea. Russia’s size and belligerence puts it in virtually its own category.

In absolute terms, Russia has been drifting toward economic insignificance for many years. The country currently ranks 11th in gross domestic product, with a smaller economy than even Italy, which has less than half as large a population.

But Russia casts a larger shadow in terms of international trade. Americans may not sense it as strongly as Europeans, because Russia is a far more important trading partner with the European Union than with the U.S. About 30% of its more than $400 billion in annual exports go to EU countries, but only about 3.5% go to the U.S.

The vast majority of those exports are in energy and raw materials. About half were in crude and refined petroleum and natural gas; Russia is the world’s third-largest producer of oil, following the United States and Saudi Arabia, and the second-largest producer of natural gas, after the United States; indeed, the Nord Stream 2 pipeline reflected Putin’s strategy of tying European countries tighter to Russia as a producer of raw materials.

These facts prompted Jason Furman, a former economist for the Obama administration, to dismiss Russia as “basically a big gas station.”

Yet that may not tell us much about how even the most stringent sanctions might affect Putin’s policies. Even the most severe sanctions tend not to produce instant course changes in the most thoroughly ostracized regimes.

That’s true for several reasons. One is that superficially ironclad sanctions are vulnerable to evasion. Pariah states aren’t always entirely devoid of trading partners, sometimes because they have resources that other countries need or because they still have political allies.

“This is going to take time,” Biden acknowledged Thursday.

The leading laboratory for the effect of sanctions is Southern Africa. Southern Rhodesia became an international pariah after its white minority government headed by Ian Smith issued a unilateral declaration of independence from Britain in November 1965.

The corporate marketing partners of the National Rifle Assn. have been dropping like flies.

British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced a raft of sanctions for which he secured international cooperation. These included bans on the import of Rhodesian tobacco and sugar, which accounted for more than 70% of Rhodesia’s exports to Britain, bans on the export of petroleum and arms to the breakaway country and its exclusion from the London securities markets.

By 1968, U.N. member states had agreed to close Rhodesia off from all goods and investments. U.N. states were required to sever diplomatic and trade relations. Airlines were forbidden to fly into or out of the country.

Wilson had predicted that the Smith government would fall in “weeks, not months.” Instead, the regime survived for 14 years. Among the causes was the support of white regimes in neighboring South Africa and Mozambique, which provided Rhodesia with goods, sometimes surreptitiously.

The most important sanctions buster, however, was the United States: Congress in 1971 authorized sanctions violations for the import of strategic materials, especially chrome. The violations continued until Jimmy Carter ended them in 1977.

The Smith government hung on until 1979, when, finally brought low by the sanctions and military pressure from neighboring countries and internal insurgents, it transitioned to Black-majority rule and became Zimbabwe.

Silicon Valley and the entertainment and biotech sectors have secured California’s reputation as an investment nirvana.

International sanctions were first imposed on white minority-ruled South Africa in the early 1960s, including a voluntary arms embargo enacted by the U.N. Security Council in 1963.

Economic and trade embargoes were gradually tightened over the following three decades, as South Africa became increasingly isolated. South Africa was expelled from the Olympics and suspended from the United Nations.

Investment bans were imposed around the globe, and Western corporations were pressured to boycott the country. In the 1980s, a divestment movement took hold; any engagement with the regime came to be seen as a marker of moral turpitude.

South Africa released Nelson Mandela, a global symbol of anti-apartheid resistance, from 27 years’ imprisonment in 1990, and he was elected president in 1994, beginning South Africa’s reintegration with the international community. It was a process that took more than 30 years.

Among the imponderables surrounding geopolitical isolation is how countries react to becoming ostracized. One concern pinpointed by Harkavy was that outcast states showed a troubling interest in acquiring nuclear weapons.

As it happens, South Africa’s last apartheid-era leader, F.W. DeKlerk, admitted in 1993 that his country had acquired a nuclear arsenal despite years-long bans on the export of nuclear weapons technology to the regime. North Korea has often displayed its purported nuclear capabilities.

And just this week, Putin issued what was widely interpreted as a veiled threat to deploy nuclear weapons against any opponents that challenged his actions in Ukraine.

Russia’s possible reactions to the sanctions being imposed in the wake of its attack on Ukraine are as murky as the justifications Putin has cited for the assault or the range of his ambitions. All that can be said for sure is that the country’s path back to international acceptance will be a long one. In the meantime, the pain inflicted on its citizens — and on those of Russia’s neighbors and partners, may well be severe.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.