How a retracted research paper contaminated global coronavirus research

- Share via

Call it the retraction that shook the coronavirus world.

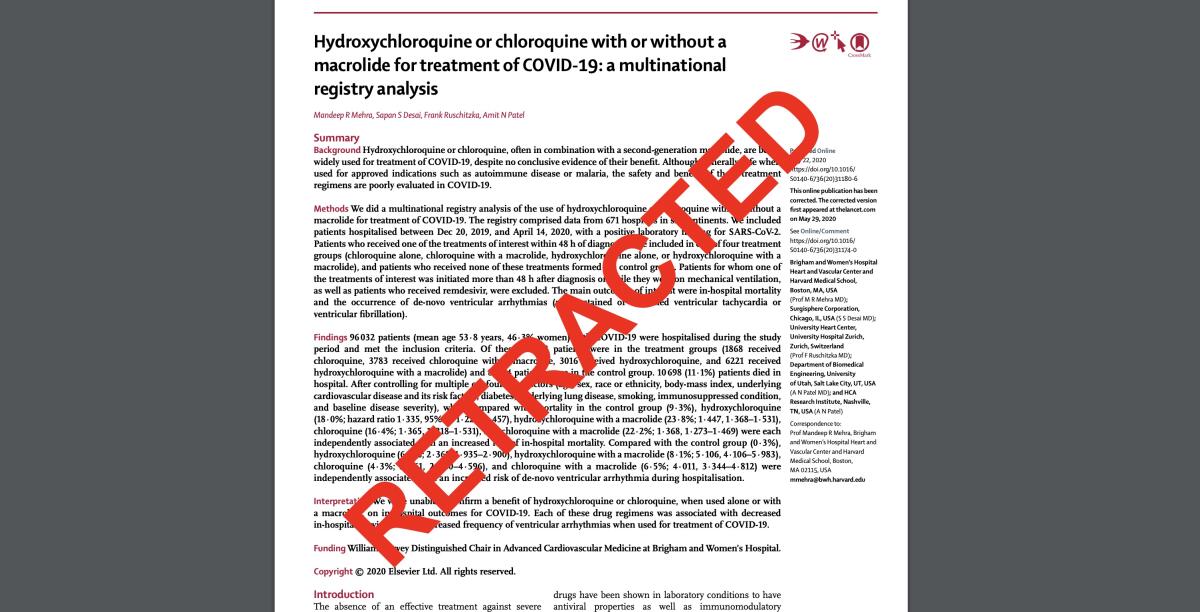

On June 4, the Lancet, the British medical journal that is one of the most prestigious scientific publications in the world, withdrew a paper that had been one of the most consequential in the novel field of coronavirus studies.

The peer-reviewed paper, which the Lancet had published on May 22, said that treating COVID-19 with the antimalarial drugs chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine raised the heart-related death risk for COVID-19 patients in the hospital without showing any benefit.

Yes, this is a wake-up call. But we’ve had the wake-up call for years.

— Ivan Oransky, Retraction Watch

The lead author of the paper, which employed a worldwide database of 96,000 patients from nearly 700 hospitals on six continents, was a highly regarded Harvard cardiac surgeon.

The findings were so striking that they prompted researchers in the U.S. and abroad, including the World Health Organization, to halt studies of the antimalarials immediately, citing the risk of heart problems.

But questions had been raised about that database almost within hours of the paper’s publication. Its retraction was followed shortly by the retraction of another paper drawn from the same database and published by the similarly prestigious New England Journal of Medicine.

The retractions are being depicted by defenders of the peer-review system of scientific publishing as evidence that the system works — the papers were published, they were subjected to painstaking scrutiny through normal scientific give-and-take, and were retracted as soon as their shortcomings were exposed.

Isn’t that how the scientific method is supposed to work?

A highly anticipated study finds that the Trump-touted coronavirus drug doesn’t work.

Well, no. The whole point of peer-review, through which submitted papers are subjected to learned examination by panels of experts in their field, is to catch shortcomings before publication.

In this case, lead author Mehreep R. Mehra of Harvard has acknowledged that he did not have direct access to the patient database itself, but was relying on an analysis by the database’s owner, a curious Chicago company called Surgisphere. When he sought access to the database after publication, he was refused.

“We can no longer vouch for the veracity of the primary data sources,” Mehra and two of his three co-authors said in their retraction statement. The name of the third co-author, Surgisphere CEO Sapan S. Desai, doesn’t appear on the statement.

It’s self-evident that neither the Lancet nor NEJM had their eyes on the ball here.

“This isn’t a story about a bad co-author,” says Leigh Turner, a bioethicist at the University of Minnesota. “There were some pretty significant breakdowns occurring within the journals.”

Worse, the breakdowns fed politically -inspired skepticism about coronavirus research in general and research into the antimalarials specifically. The chief culprit in this effort to undermine science is President Trump, who turned the use of the antimalarials as treatments for the pandemic into a partisan cause.

Sure enough, Trump’s reelection campaign exploited the publication fiasco for its own purposes. The original study, the campaign asserted, “was gleefully promoted by the mainstream media in an attempt to discredit and attack President Trump.”

The coronavirus crisis shows how the free sharing of data is crucial in science.

Noting that Trump has often been accused of waging a “war on science,” the campaign crowed: “The actual war on science was being waged by the people behind the study and The Lancet.”

The inadequacies of peer review have been understood for some time. “Yes, this is a wake-up call,” says Ivan Oransky, whose Retraction Watch website tracks withdrawals of research papers, of the Lancet and NEJM retractions. “But we’ve had the wake-up call for years.”

In perhaps the most notable reversal of judgment of a scientific paper, the Lancet in 2010 retracted a study by British researcher Andrew Wakefield purporting to link autism to the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

But the retraction only came 12 years after the Lancet had published the study, which has been conclusively debunked. In the interim Wakefield’s research had come under heavy scientific fire.

Soon after the retraction, Wakefield lost his license to practice medicine in Britain. But he remains a prominent figure in the anti-vaccine movement and his debunked paper fuels anti-vaccine activity to this day.

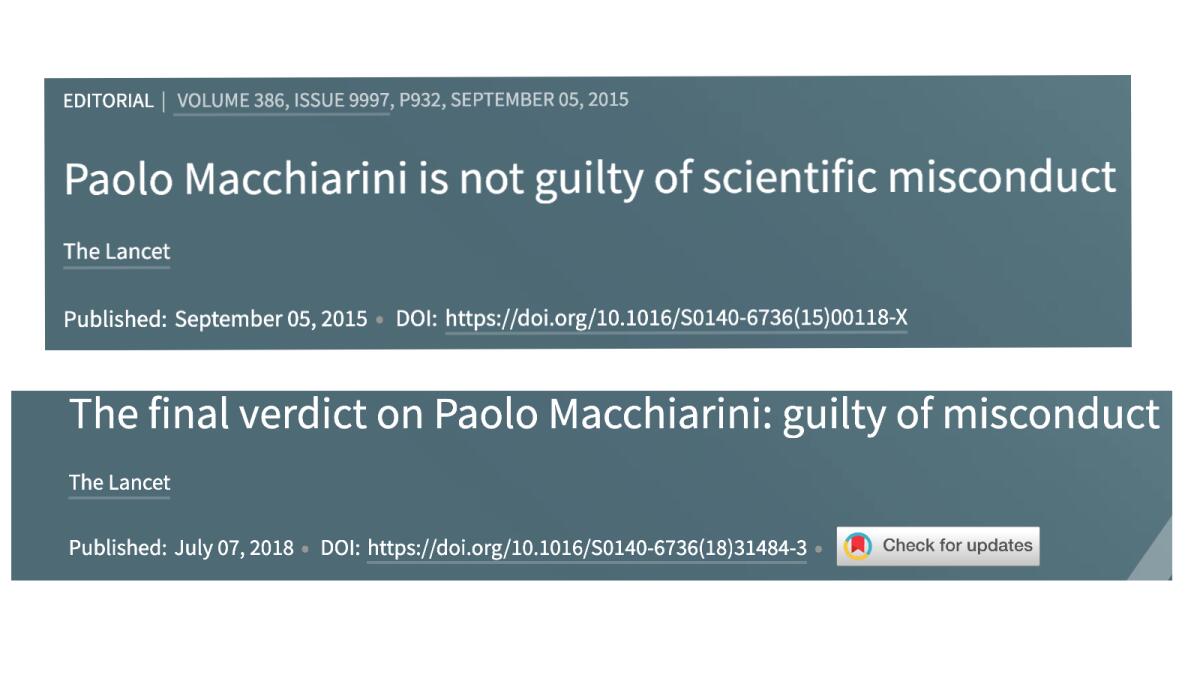

The Lancet also supported Paolo Macchiarini, an Italian surgeon whose claim to have developed a stem cell-engineered artificial trachea had been widely touted, including an admiring special report by NBC News anchor Meredith Vieira. The claim was eventually deemed to be the product of unethical and deceptive work.

“Paolo Macchiarini is not guilty of scientific misconduct,” the Lancet declared in 2015, citing a finding by the Karolinska Institute, where Macchiarini held a research position. “Dragging the professional reputation of a scientist through the gutter of bad publicity ... was indefensible,” the Lancet opined.

History tells us that rushing a vaccine for COVID-19 will prove more hazardous than if it’s done right.

Three years later, when the Karolinska reversed itself, so did the Lancet, with a headline reading: “The final verdict on Paolo Macchiarini: guilty of misconduct.” The journal also retracted two papers by Macchiarini that had been published in 2011 and 2012.

By those standards, the retractions of the coronavirus papers happened with lightning speed. But given the politically charged environment and the global desperation for a treatment for COVID-19, the original papers were especially damaging to respect for the scientific process.

The retractions threatened to undermine the credibility of the first large objective study of the antimalarial drugs as treatments for COVID-19. That’s a study of 821 subjects who had been exposed to the virus either in their households or at work as healthcare professionals or first responders, and were then treated either with hydroxychloroquine or a placebo.

This study, led by the University of Minnesota and published by the New England Journal on June 3, found that the drug was useless in preventing infection by the coronavirus.

That brings us to the weird aspects of the retracted studies. Let’s take a look.

Questions about the research first arose in Australia, where it was reported by the Guardian Australia that the Lancet paper cited more COVID-19 deaths in that country than had actually occurred during the paper’s time frame. Surgisphere explained that data from an Asian hospital had been mistakenly added to the Australian figures. The Lancet ran a brief correction.

But the glitch prompted closer scrutiny of Surgisphere and its database. Medical authorities wondered how a small company with roughly a dozen employees could have assembled a worldwide patient database with tens of thousands of samples.

Compiling such data, ensuring that individual identities are deleted, and then creating software tools to make the database useful, take years and the work of large teams to reach agreements with the hundreds of hospitals that would be contributing their patient records. That seemed way beyond Surgisphere’s capabilities.

Desai turned away requests for access to his raw data. He didn’t respond to our request for comment, but on May 30 the British journal The Scientist quoted him as stating that he would be willing for his database to be audited by an “external, third party, independent of who we are, [which] can help validate all of this.”

Yet after the first questions emerged, Mehra and the other co-authors ran into a brick wall when they launched what they described as their own “independent third-party peer review of Surgisphere ... to evaluate the origination of the database elements, to confirm the completeness of the database, and to replicate the analyses presented in the paper.” Their retraction followed.

Hoover also ordered an attack on peaceful protesters -- and lost the presidency.

Harvard’s Mehra portrays himself rather as a victim of his own ambition to answer an important health question, and of a company that seemed to offer exactly the data he required. He suggests the desperate quest for information led him to kick his professional standards to the side.

“It is now clear to me that in my hope to contribute this research during a time of great need, I did not do enough to ensure that the data source was appropriate for this use,” he told me by email. “For that, and for all the disruptions — both directly and indirectly — I am truly sorry.”

Yet is that enough? In the original paper, Mehra states that he and co-author Amit Patel “had full access to all the data in the study.” Now he’s saying that wasn’t so.

As we’ve observed previously, the frenzy to find a treatment or cure for COVID-19 has led to the removal of numerous barriers that have blocked or slowed the dissemination of scientific research in the past. That’s especially true of barriers erected by the for-profit model of scientific publication.

In many ways, that’s a good thing. The sharing of information is especially important at this moment, when a still-misunderstood pathogen is threatening the world. But it can also result in the dissemination of half-baked or unbaked research. That’s not necessarily a big problem as long as “preprints,” papers that have not yet undergone peer review, are labeled as such.

But when half-baked research arrives with the imprimatur of the world’s ostensibly most credible journals, it’s time to wonder if they have let their devotion to scientific rigor take second place to their desire for impact.

“These journals are major brands,” Turner told me. “That gives them an incentive to swing for the fences in terms of dramatic publications.” Few papers could be more dramatic in the current atmosphere as a study conclusively debunking a popular nostrum, based on an immense sample of 100,000 patients.

A lot more needs to be disclosed about this affair before the smoke clear. Mehra and his colleagues will need to explain how they came to rely on a database they can’t vouch for. Desai will have to explain the origins of the database, if it even exists.

And the Lancet and NEJM will have to explain how they came to publish papers that they had to retract within two weeks. A lot is riding on their transparency, because without that, why should anyone trust anything they publish?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.