Fruit breeder hits the sweet spot with Cotton Candy grapes

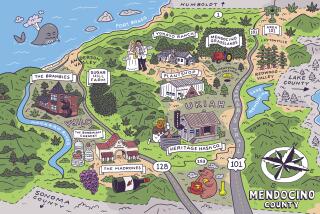

It’s not easy peddling fresh fruit to a nation of junk-food addicts. But in rural Kern County, David Cain is working to win the stomachs and wallets of U.S. grocery shoppers.

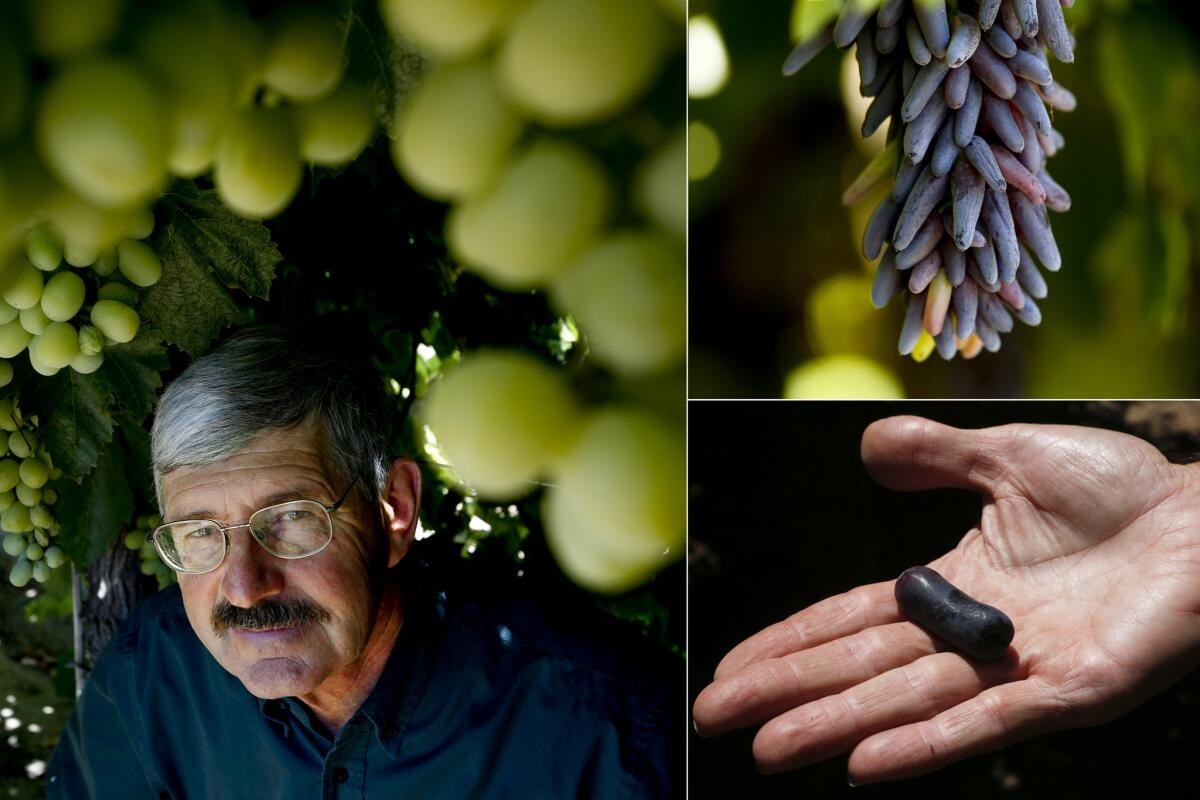

Cain is a fruit breeder. His latest invention is called the Cotton Candy grape. Bite into one of these green globes and the taste triggers the unmistakable sensation of eating a puffy, pink ball of spun sugar.

By marrying select traits across thousands of nameless trial grapes, Cain and other breeders have developed patented varieties that pack enough sugar they may as well be Skittles on the vine. That’s no accident.

“We’re competing against candy bars and cookies,” said Cain, 62, a former scientist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture who now heads research at privately owned International Fruit Genetics in Bakersfield.

In an intensely competitive marketplace, breeding and branding have become almost as valuable to farmers as sun and soil. Producers are constantly tinkering, hoping to come up with the next Cuties Clementine orange or Honeycrisp apple — distinct products that stand out in the crowded fruit aisle.

“People are looking for more flavor,” said Mark Carroll, senior director for produce and floral at Gelson’s Markets, which will carry the Cotton Candy grape. “Once they get hooked, they want more no matter what.”

Cain’s company, in the heart of California’s $1.1-billion table grape industry, specializes in bold flavors and exotic shapes. Purple-hued Funny Fingers are long and thin like chili peppers. A variety named Sweet Sapphire come as round and fat as D batteries. Like the Cotton Candy, the special varieties are patented, then licensed to growers. The Funny Fingers are marketed as Witch Fingers and are available at high-end supermarkets. The Cotton Candy will be available this month.

Ordinary grapes like the red Flame Seedless can cost as little as 88 cents a pound. The Cotton Candy could fetch around $6 a pound, though prices would come down if enough growers cultivate the grape.

The U.S. designer-fruit craze kicked into high gear in the late 1980s. That’s when a Californian plum-apricot hybrid called the pluot hit the market. The crispy stone fruit, which took 20 years to develop, proved such a hit with consumers that it inspired more farmers to invest in breeding programs to boost sales.

California is now churning out other sweet inventions, including apriums (a pluot but with more apricot), peacharines (peach and nectarine) and cherums (cherry and plum).

Not to be confused with GMO engineering, cross-breeding techniques employed by fruit breeders are centuries old. In the case of grapes, pollen from male grape flowers is extracted and then carefully brushed onto the female clusters of the target plant. Then comes a lot of waiting. Then replanting. Then repeating the process — for years, even decades.

“It’s a bit like fishing. You never know when you’re going to get the big one,” said Cain, a soft-spoken man who would look every bit the lab coat-clad scientist if it weren’t for the soil under his nails.

Fruit breeders have made California No. 1 when it comes to grapes. Almost all the table grapes commercially grown in the U.S. come from the Golden State, which shipped a record 100 million boxes last year.

Still, to stay competitive in the nation’s lunchboxes, growers must keep developing new tastes.

Columbine Vineyards in Delano, Calif., already has two successful patented varieties, the cranberry red Holiday Seedless and the ultra sweet Black Globe, a seeded berry with a strong following in Asia. More are in the pipeline.

“We have people constantly testing for new varieties,” said Lauren Olcott in the farm’s sales and marketing office. “It can take 15 years or more for something to mature, so you have to wait.”

Although some of these grapes have been bred for higher sugar content, nutritionists don’t seem all that bothered.

“You would have to eat about 100 grapes to consume the same amount of calories in a candy bar,” said David Heber, director of the UCLA Center for Human Nutrition.

Cain got his start in the 1970s as a researcher with the USDA developing new varieties of table grapes and seedless raisins in Fresno. Then, most fruit breeding was done by the government or universities that could afford the time-consuming and expensive work.

He jumped to the private sector in 1987, just as U.S. grape consumption was exploding, thanks to new seedless varieties developed in California.

Cain helped start International Fruit Genetics in 2001. A few months later at a trade event he tasted the grape that has obsessed him ever since.

Researchers from the University of Arkansas were showing off a purple Concord grape that didn’t look like much. The flesh was mushy and speckled with tiny seeds. The skin slipped off easily after biting, a no-no in the grape business. But the cotton candy flavor transported Cain to a carnival or county fair.

What if he could take the unique flavor of that Eastern U.S. native and meld it with Californian qualities such as superior crunch, thin skin and generous size?

International Fruit Genetics signed a licensing agreement with the University of Arkansas. By 2003, Cain was cross-pollinating their grapes with a dozen California varieties on his test field, 80 acres of dusty vineyards in Delano, north of Bakersfield.

On a recent weekday, Cain showed why he spends half his time was spent outdoors. Rows and rows of vines needed to be inspected in search of the next big thing. Carrying a tool belt and a refractometer to measure the sugar content of each grape, Cain methodically tasted his berries, deciding what to keep and what to toss. With 300 kinds of grapes to taste on each row, swallowing the fruit is out of the question.

“I’ve learned to do a lot of spitting,” Cain said.

First came a set of green grapes showing signs of early ripening — a valuable quality. Cain tied a blue and white ribbon around its root to signify a keeper.

The next bunch was red tinged with green at the tips — as likely to confuse consumers as attract them. Cain spritzed the root with orange spray paint, a reminder to dispose of the grapes later.

It was this same painstaking process that led Cain to find the ideal mate for his spun-sugar-flavored Concord, a green beauty called Princess. That variety was developed by the USDA and is known for its crisp texture and juiciness.

After five more years of test planting, the Cotton Candy was patented in 2010. A Bakersfield grower is set to harvest the first large crop as soon as next week.

Cain doesn’t like to fuss over such milestones, but the Cotton Candy has him jazzed. He thinks its signature flavor has a chance to hook consumers like nothing before.

“It’s going to be introduced slowly,” Cain said. “Whether it will be a niche grape or start a revolution is hard to say. What we’re hoping is it will do for grapes what all these new varieties have done for fruit like apples.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.