TSA says an airport full-body scanner must add a filter to protect travelersâ privacy

A full-body scanner that the Transportation Security Administration hopes can speed up airport security checkpoints must go back to the drawing board for software to protect the privacy of travelers being scanned.

The scanner, built by British firm Thruvision, was promoted as being able to simultaneously screen multiple airport passengers from a distance of up to 25 feet away. The TSA began trying out the device last year at an Arlington, Va., testing facility before planning to use it on a trial basis at U.S. airports.

But now the federal agency is requiring the scanner to add a âprivacy filterâ before the TSA can test the scanner âin a live environment,â according to a TSA document.

The March 26 document was posted on a public website, but many details were redacted, including the name of the manufacturer and the cost of adding the privacy filter.

In a statement, Thruvision confirmed that the TSA document referred to the Thruvision scanner, which is currently being used at some Los Angeles subway and light-rail stations.

TSA and Thruvision said the software is being added to comply with a federal law passed in the wake of a 2013 controversy involving body scanners that may have shown too much.

The scanner doesnât violate travelersâ privacy or show details of a personâs anatomy, Thruvision Americas Vice President Kevin Gramer said.

Images provided by Thruvision show that the scanner creates a fuzzy, green image depicting a travelerâs body with a dark outline of potential weapons or explosives that are hidden under their clothes.

âA piece of narrowly drawn legislation from several years ago created a requirement that all people-screening technologies used at U.S. airport checkpoints have a privacy filter regardless of the image displayed,â Gramer said in a statement. âThruvision screening equipment has been deployed internationally for years because of the tremendous privacy and safety benefit of its passive terahertz technology and it is a candidate for use at U.S. airports specifically because of those benefits.â

In 2013, the TSA removed about 200 full-body scanners after protests because the scanners used low levels of radiation to create what resembles a nude image of screened passengers. Critics called the device the ânudie scannerâ before the TSA ended its contract with the manufacturer.

Three years later, Congress adopted legislation requiring that all full-body scanners used at U.S. airports include privacy software filters that keep the devices from showing details of a travelerâs body on the screens monitored by the TSA.

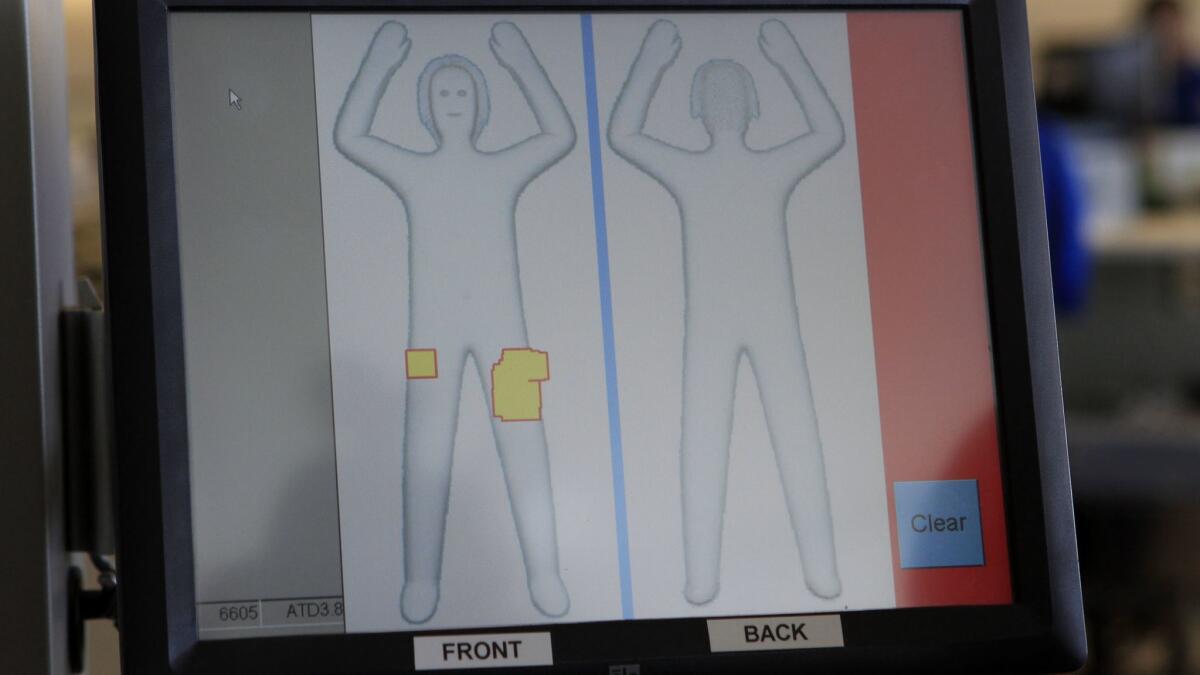

The full-body scanners used at the nationâs airport create a generic human avatar of each traveler that appears on TSA screens. Weapons or explosives hidden under the travelerâs clothes are shown as yellow squares on the screen.

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority in Los Angeles began using Thruvision scanners last year. An MTA spokesman said the transportation agency bought a handful of Thruvision devices but did not add privacy software because the images created by the device donât show details of a commuterâs anatomy but instead depict each person as a âgreen blob.â

The Thruvision scanner is one of several new technologies being tested under the TSAâs âInnovation Task Forceâ as part of an effort to improve screening and speed up the queues at airport security checkpoints.

The task forceâs efforts included the 2016 launch of a new conveyor belt system to move luggage and passengers through a security checkpoint faster.

Under the full-body scanning program, the TSA purchased several Thruvision devices to begin testing in November 2018.

The existing full-body scanners used at U.S. airports bounce millimeter waves off passengers to spot objects hidden under their clothes. But Gramer said the Thruvision device uses a passive terahertz technology that reads the energy emitted by a person, similar to thermal imaging used in night-vision goggles.

Thruvision has promoted its scanning devices as being able to screen up to 2,000 people in an hour and detect a concealed weapon at a distance of up to 25 feet.

The screening device was used in 2017 to scan people attending a tribute concert organized by U.S. singer Ariana Grande after her May 22, 2017, concert in Manchester, England, ended in a suicide bombing that killed 23 people and wounded 139 others.

To read more about the travel and tourism industries, follow @hugomartin on Twitter.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.