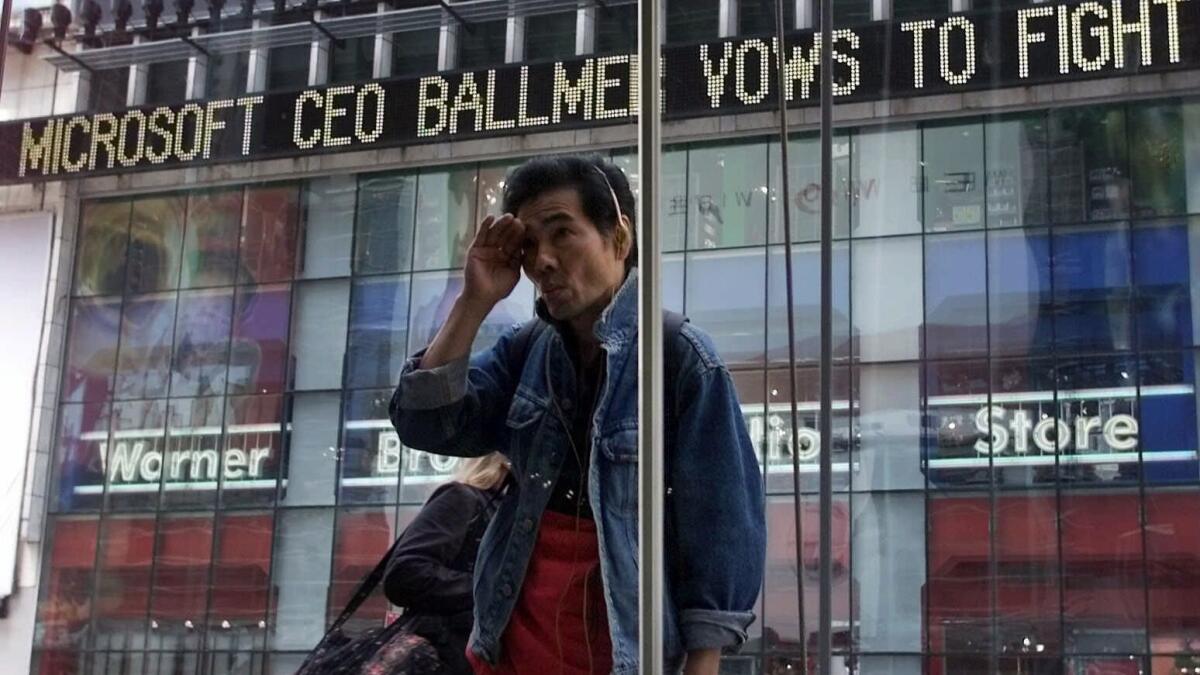

Microsoftâs past antitrust missteps offer lessons for todayâs tech giants

Of the five biggest tech companies in the U.S., Microsoft is the only one that isnât currently in the crosshairs of U.S. antitrust authorities. The software giant already took its turn through the regulatory wringer starting two decades ago, a years-long confrontation that resulted in the finding that the Redmond, Wash.-based company had illegally maintained its monopoly for personal-computer operating-system software.

The case dealt with the companyâs moves to kneecap the Netscape web browser by bundling its own product, Internet Explorer, into Windows, the dominant PC operating system. A federal judge ordered the company split in two in 2000, a fate Microsoft avoided when an appeals court reversed that part of the ruling and the company eventually settled. That 2002 settlement led to nine years of court supervision of the companyâs business practices and required Microsoft to give the top 20 computer makers identical contract terms for licensing Windows, and gave computer makers greater freedom to promote non-Microsoft products like browsers and media-playing software.

Because observers and legal pundits almost uniformly agree the software giant did virtually everything wrong in the course of the investigation â which had its start as early as 1990, followed by a 1998 Justice Department lawsuit â in retrospect its story serves as a useful instruction manual of what not to do.

Though no formal inquiries have yet been opened, the Federal Trade Commission and Justice Department carved up the territory of big tech â Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., Alphabet Inc.âs Google and Facebook Inc. â as they prepare to dig in on antitrust issues.

The Department of Justice will look at Google, which dominates the online search and advertising spaces, and Apple, whose pervasive App Store is likely to be under examination. The FTC drew Facebook, with its behemoth social networking and messaging apps and a slew of recent privacy missteps, and e-commerce giant Amazon, which has been pushing into areas like grocery and health.

As these companies build their legal teams and prepare strategies for the fight ahead, here are several lessons that Google, Amazon, Apple and Facebook can learn from Microsoftâs battle with the feds.

1. Donât deny the obvious

Or donât even put up a fight about whether you have a monopoly. Microsoft, whose Windows software accounted for about 90% of the market for PC operating systems, opted to argue that the space was actually competitive. Parts of the argument included videos where Microsoft employees offered a straight-faced marketing pitch for the benefits of rival Linux programs with a tiny share of the market.

The impulse is understandable â monopoly sounds like a dirty word. But U.S. antitrust law doesnât expressly forbid having a monopoly; it outlaws doing certain things to establish, maintain or extend one. That led some legal scholars to argue that Microsoft would have been better served by copping to the Windows monopoly and establishing a legal beachhead against the idea that it did anything illegal to gain it or keep it. Arguing against something so self-evident via the companyâs first witness strained credibility and started off the case on a bad footing.

Itâs easy to imagine a similar issue applying to Google, which has more than 84% of the web-search market and controls 82% of mobile-phone operating systems. In the app-store business, Google and iPhone maker Apple together control more than 95% of all U.S. mobile app spending by consumers, according to Sensor Tower data.

Apple CEO Tim Cook earlier this month told CBS that his company doesnât have a dominant position in any market. But regulators may look at the power it wields through its App Store. It could be more effective for these companies not to start by denying that leadership position â if you have 80% or 90% of a market, arguing that you donât really dominate isnât the hill you want your legal reasoning to die on.

2. Donât resort to spin

Microsoftâs credibility with the press was no higher, hurt by constant counterfactual statements and spin. Each day, after a bruising in court as government lawyer David Boies poked holes in executive testimony and Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson alternated between chuckling at the witnesses and chastising them, Microsoft deployed a hapless PR person to the steps of the courthouse to recite the words, âToday was another good day for Microsoft.â It never was.

3. Assume everything will be made public

Among the list of horrifying moments for Microsoft in court was the public showing of parts of the 20 hours of depositions of co-founder and Chief Executive Officer Bill Gates. The tapes (yes, they were tapes â this was the â90s) showed an ill-lighted, evasive and combative Gates engaging in Clintonian word-wrangling, such as asking about the definition of the word âdefinitionâ and arguing what âmarket shareâ meant.

Microsoft claimed it had been assured the tapes would never be shown in court, or the company would have taken greater care with Gatesâ appearance and manner. During their playback in court, the judge laughed at several points â not the impression the software giant wanted to make on either Jackson or the public. Jackson told New Yorker reporter Ken Auletta that Gates came off as âarrogantâ in the depositions.

Just as bad for Microsoft, an array of internal emails were read aloud in court that contradicted the testimony of its executives, which further angered Jackson. The takeaway? Assume everything will be aired in the court of public opinion. If it was true 20 years ago, itâs even more apparent in the current era of oversharing, thanks to the tech companiesâ own services.

4. Donât be condescending about the technology

Most lawyers, judges and regulators donât appreciate being told or having it implied that they lack the ability to apprehend certain tech concepts. Or that the reason they think thereâs been an antitrust violation is because they just donât âgetâ the technology. It was true that Jackson and Boies seldom used a computer at the time. But it didnât require a computer science doctorate to divine the legal merits of the case.

At the height of Microsoftâs hubris (or carelessness, or both), the company sent Windows chief Jim Allchin to the stand with a doctored video that purported to show how computing performance would be degraded when the browser was removed from Windows on a single PC. It was actually done on several different computers and was an illustration of what might happen rather than a factual test, as the company initially claimed â a fact that came to light only after several days of the government picking through every inconsistency in the video. Microsoft remade the simulation several times in an effort to save the testimony.

The company seemed to think it could get away with baldy stating a technological claim and mocking up something that backed it up, perhaps reasoning that no one would know the difference, but it miscalculated badly.

5. Choose your lawyers wisely

Microsoft took on the U.S. government led by a combative Gates and an equally aggressive general counsel, Bill Neukom. Gates, the son of an attorney, was outraged, frustrated and convinced the company was being unfairly targeted. One of the companyâs outside lawyers, from the firm Sullivan & Cromwell, said the company could put a ham sandwich into Windows if it wanted to. And throughout, Neukom not only failed to tamp down his executivesâ worst impulses, he seemed to amp them up. His legal style led observers to point out that his last name â pronounced ânuke âemâ â was quite fitting.

The U.S. governmentâs latest antitrust targets should take heed: If your top executiveâs style tends towards waving a red flag in front of a bull, you may be wise to consider a top lawyer with a more conciliatory style. Googleâs top executives have already raised the ire of lawmakers for refusing to appear before Congress, and no one has ever accused Jeff Bezos of being afraid of a fight. At Facebook, where Zuckerberg regards Gates as a mentor and observers see similarities in their styles and temperaments, this lesson might be particularly important.

6. There are many different ways to lose

Right now, the companies are at risk of only an inquiry â the agencies are deciding what, if any, action to take. But even at this stage, they should keep in mind that a loss doesnât only mean a full-scale breakup or forced divestiture. Companies can avoid that extreme fate and still find, as Microsoft did, that the years of distraction from the fight have hampered their business and sucked up executive time and mental energy.

In an interview last year at the Code Conference, Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith lamented the distraction the case caused, and cited it as a reason the company missed out on the search market â the business that fueled the runaway success of Google, now under the microscope itself. Others have pinned Microsoftâs abysmal performance in mobile computing partially on constraints and distractions from the case. Some of the companyâs business missteps can fairly be attributed to poor execution and strategic errors that had nothing to do with the government dispute.

Still, the notion that merely fighting an antitrust battle may do almost as much harm as losing one brings us to our last point.

7. Consider settling early

Itâs hard to say with certainty what the late 1990s and early 2000s might have looked like for Microsoft had it found a way to settle with the government earlier than 2002. Still, for the governmentâs current targets, itâs worth weighing a settlement against the effect of several years of investigation, a possible loss in court and potentially harsher restrictions or remedies.

Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google probably have a pretty good idea of what regulators may object to, and itâs worthwhile for them to consider ways to assuage those concerns while keeping the core of their businesses and future ambitions intact. The alternative is years of investigations, possibly damaging evidence and testimony, and ample distraction, all leading up to what could be a devastating loss in court.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production â and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.