We asked Californians to give us their tax returns. Here’s how the GOP plan would affect them

Republican tax plans are working their way through Congress. If the House and Senate can agree on a final bill, will you owe more or less? The answer, of course, is it depends.

It depends on how much you make, but also on other factors, such as whether you own or rent, whether you have kids and whether you’re a student.

To try to figure out how Californians would be affected, we asked Times readers to provide us their 2016 tax returns. We then took a sampling of those returns, and with the help of accounting firm Marcum, applied key elements of the different tax plans passed by the House and Senate. The result is a set of hypothetical returns that show what taxpayers would have owed had either of those plans been law last year.

Though they are just a snapshot, the returns suggest that there will be winners — and losers — under either version. Renters and other taxpayers who don’t take many deductions may see their tax bills fall. Homeowners, especially ones with pricier properties, could pay more.

Still, Rob Babek, a Marcum partner who reviewed returns for The Times, cautioned that much of this could change as GOP leaders work to reconcile the two bills into one tax plan.

“In one of these examples, someone would pay $800 more under the House version but save $500 in the Senate plan,” Babek said. “It’s really hard to tell where someone is going to end up until they come up with a final document.”

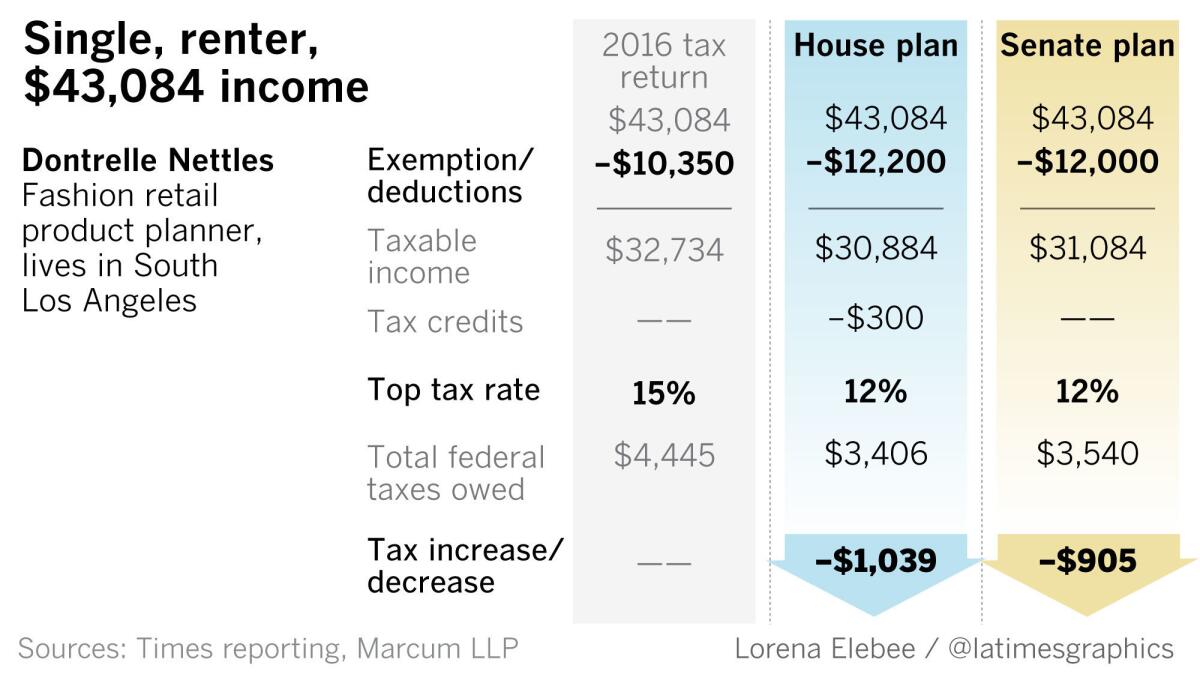

Dontrelle Nettles, a 27-year-old South Los Angeles resident, would see his federal tax bill go down under both the House and Senate plans.

Nettles made about $43,000 in 2016 working for now-defunct fashion retailer and manufacturer American Apparel. He’s now a product planner at Hollywood fashion retailer Chrome Hearts.

Nettles is single and has no children, so he took a single exemption that cut $4,050 from his taxable income. He rents a home, so he can't deduct mortgage interest or property taxes. He could have deducted his California income taxes, but those amounted to just about $1,200, so he was better off taking the standard deduction of $6,300.

That left him with taxable income of $32,734. He paid as much as 15% in taxes on part of that income, giving him a federal tax bill of $4,445 last year.

Both plans eliminate personal exemptions but also nearly double the size of the standard deduction to $12,000 or more, meaning Nettles would see his taxable income fall. He’d also pay a lower marginal tax rate, owing at most 12% on any portion of his income, and get a new $300 tax credit under the House bill.

That means his taxes would fall $905 under the Senate plan and $1,039 under the House plan.

Though the tax overhaul could put more money in his pocket, Nettles said that even the greater benefits of the Senate plan wouldn’t be a game-changer for him — and he worries about the long-term effects on the nation.

Like many opponents of the tax overhaul, he’s concerned that it provides much larger benefits to the wealthy and could lead to larger deficits and eventually cuts in programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

“I have quite a while before I retire, but I wonder how little changes now may affect me later,” he said.

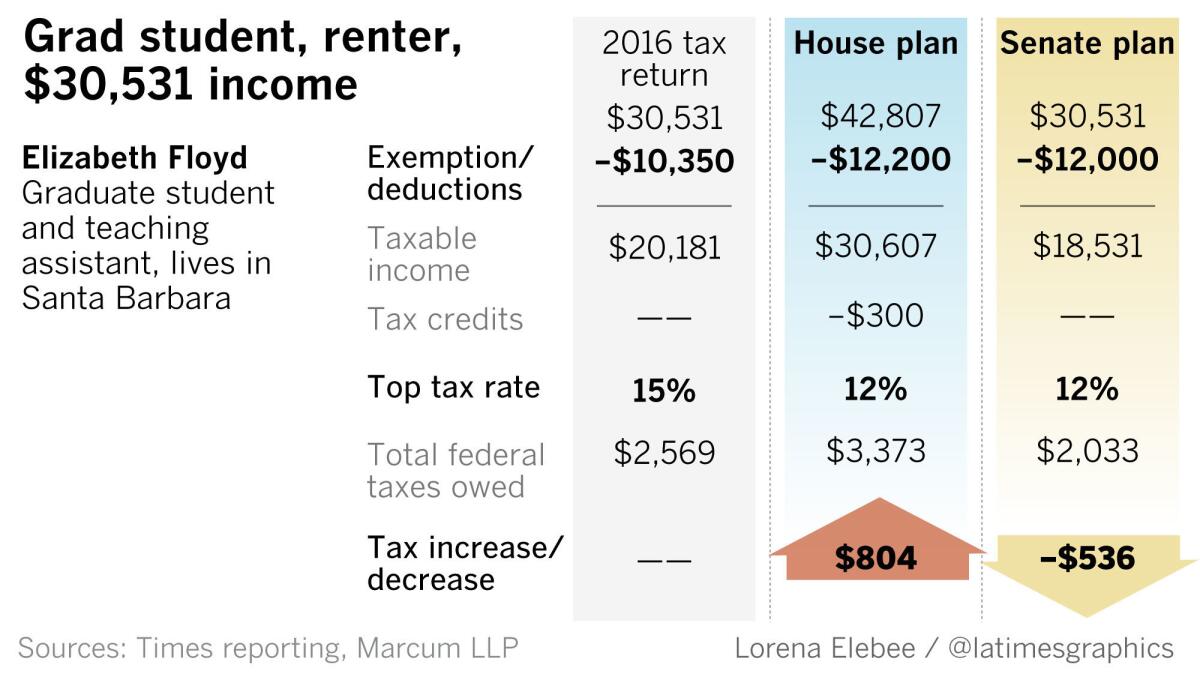

Elizabeth Floyd, a 30-year-old graduate student and teaching assistant at UC Santa Barbara, would see her tax bill cut by the Senate changes but would face an increase under the House plan.

Floyd, who’s studying post-World War II British literature, made about $30,500 as a teaching assistant and summer school instructor in 2016. She also paid nothing in tuition. Last year, her federal tax bill totaled $2,569.

Under the Senate plan, she’d see her federal tax bill go down. She took the standard deduction last year because she doesn’t own a home and doesn’t pay much in state income taxes. With the standard deduction nearly doubling to $12,000 and lower marginal tax rates, she’d owe $2,033, a tax cut of $536.

But under the House plan, she would owe more money even though its standard deduction is $200 more generous than the Senate version. That’s because the House proposes to count her free tuition as income — a change from the current tax code.

Taxing her free grad school tuition of $12,276 would increase her income to almost $43,000. (If she were attending a private university where tuition can be nearly four times that, she would be worse off.)

Despite the larger standard deduction, a lower marginal tax rate and a $300 tax credit, her tax bill would climb to $3,373, an increase of $804.

Floyd said her budget is already tight. Living in pricey Santa Barbara, she shares a two-bedroom apartment and pays $1,150 a month in rent, which eats up about half her take-home pay.

“I’m very much living paycheck to paycheck, and my income is only guaranteed for nine months of the year,” she said. “Whatever I’m able to save is so I can get through the other three months.”

Like many graduate students, she’s concerned that the House plan would make post-graduate education unaffordable for more would-be students.

“You want a well-educated society,” she said. “People getting PhDs, they’re the future educators of America. And having graduate students makes universities function. Tuition remission is one of the few benefits we get.”

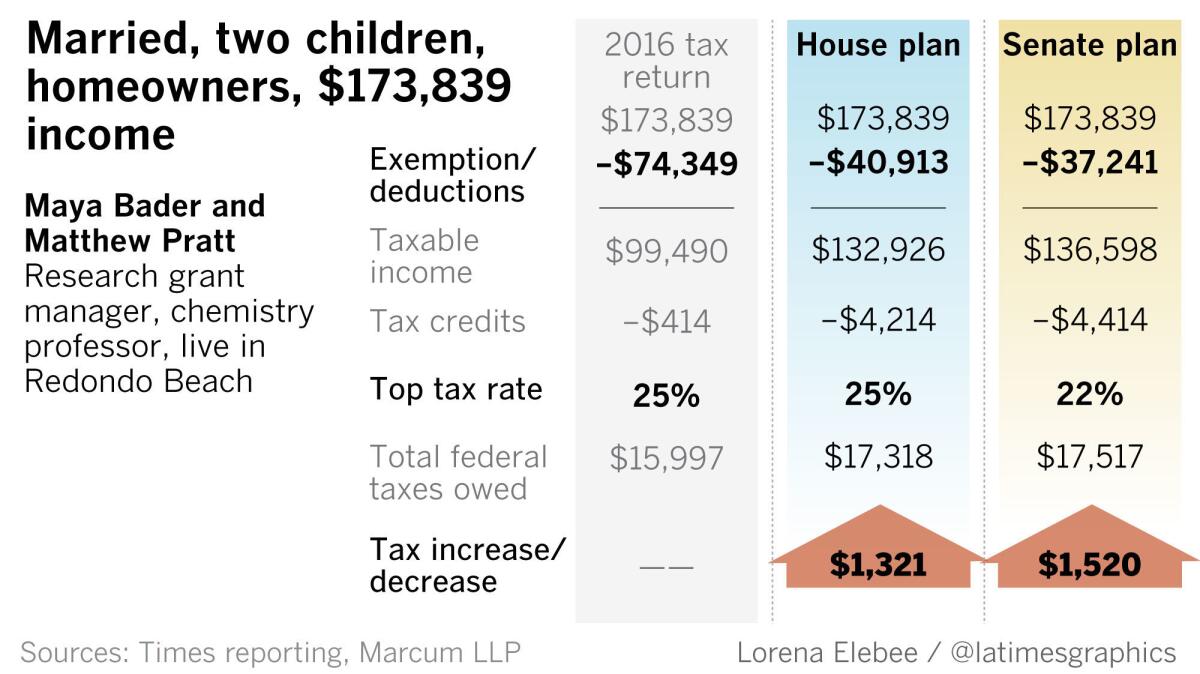

Maya Bader, 39, is a grants manager at the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network, an area nonprofit. Her husband, Matthew Pratt, 40, is a chemistry professor at USC.

The pair, who have doctorates, have two children — a 5-year-old and a 15-month-old — and about $174,000 in combined annual income. They also have a new house, with a big mortgage and a big property tax bill.

In March 2016, they bought the home, their first, paying $915,000, which got them three bedrooms and two baths in Redondo Beach.

After exemptions for themselves and their kids, and after taking big deductions for their property taxes, mortgage interest and California income taxes, Bader and Pratt had taxable income of less than $100,000 and a federal tax bill of $15,997.

Under both the House and Senate tax plans, they would pay more, though not by much.

Like all taxpayers, they would lose $4,050 personal exemptions for themselves and their kids.

They also would no longer be able to deduct their state income taxes, which were more than $12,000 last year, and would be unable to deduct all their property taxes. They paid nearly $14,000 in property taxes last year, but would be able to deduct only $10,000 under both the House and Senate plans.

They would, however, still be able to deduct most or all of the interest stemming from their home debt.

Under the Senate plan, they would be able to deduct all the interest on their $732,000 first mortgage, but would lose the interest write-off on a $90,000 home equity loan they took out for the purchase. Under the House plan, they could deduct the interest on both (though future home buyers would be unable to deduct interest on mortgage debt above $500,000 and any interest for new home-equity loans.)

Compensating for their loss of exemptions and deductions, though, are more generous child tax credits.

Those credits last year would have knocked $1,000 per child off their tax bill, but Bader and Pratt made too much to qualify. Under the new proposals, the credits would get larger — $1,600 per child in the House plan, $2,000 in the Senate version — and be available to families that make more money. The House plan would also provide a $300 credit to Bader and Pratt themselves.

All told, under the House plan they’d see a tax increase of $1,321; under the Senate plan it would be $1,520.

That’s not make-or-break money for Bader and Pratt, and they aren’t bothered at the notion of paying more. They’re big believers in government programs — Pratt noted that much of his research is funded by government grants — and said they were surprised by how little they paid in federal taxes last year.

“I think we’re undertaxed,” Pratt said. “It was quite surprising to me, once we started itemizing our deductions, how little we pay.”

They would prefer, however, that their small tax increase help pay for schools or medical research or affordable housing instead of a lower corporate tax rate and an exemption that would allow more wealthy families to avoid paying the estate tax.

“We’re not mad about the taxes, Bader said. “We’re mad about what they’re being used for.”

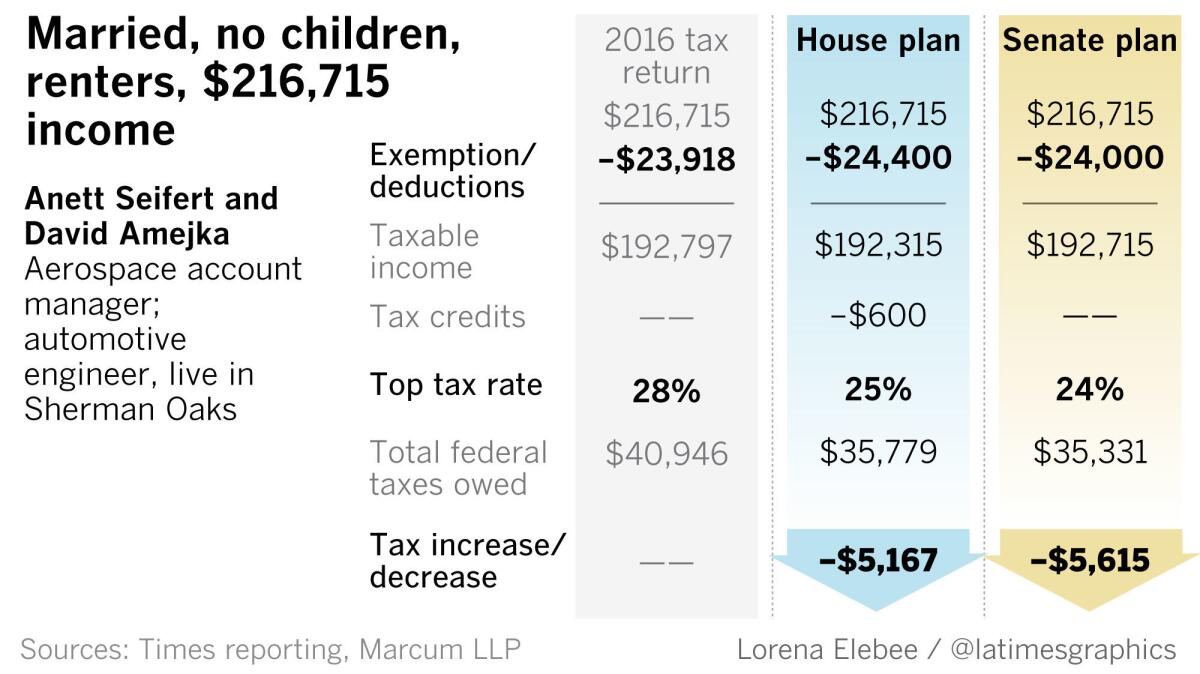

Anett Seifert, 33, and David Amejka, 39, are a married couple who make good money, don’t have children and rent their house — a combination that results in a high federal tax bill.

She’s an account manager at a Burbank aerospace firm; he’s an engineer for Mercedes-Benz in Long Beach. Together, they made about $217,000 last year and paid about $41,000 in federal income tax.

They took a total of about $24,000 in exemptions and deductions: Almost $16,000 in deductible state income taxes, plus personal exemptions of $4,050 apiece.

Without owning a home, they can’t take the deductions for mortgage interest or property taxes — items that result in big tax savings for homeowners in pricey Southern California. (By comparison, Bader and Pratt deducted about $27,000 in mortgage interest alone last year.)

Under both the House and Senate plans, Seifert and Amejka would no longer be able to deduct their state taxes and would lose their personal exemptions, but they’d still wind up with sizable tax cuts.

Both plans call for a larger standard deduction — $24,400 in the House plan for couples, $24,000 in the Senate — that would essentially match their current exemptions and deductions without itemizing.

That means they'd be paying federal taxes on almost exactly the same amount of taxable income, while lower marginal tax rates in both plans would result in thousands in savings.

Last year, they paid as much as 28% on some of their income. Under the House plan, they'd pay no more than 25%; the Senate plan would charge them no more than 24%.

All told, the House plan would give them an estimated tax cut of $5,167 and the Senate, $5,615.

The couple would be happy to the get a tax break but still thinks the plans don’t go far enough to even the playing field between homeowners and renters.

“We have a lot of housing costs, too,” said Seifert, noting the couple pays $3,500 a month for their home. “But we rent and there’s no incentive for that.”

Seifert and Amejka described their financial situation as comfortable and said they are not interested in buying a home — at least not for the seven-figure price tags that are common in their neighborhood.

"We have no debt," Amejka said. "We don’t owe anybody anything. I like it that way."

How we did it: Participants submitted copies of their 2016 federal tax returns, which were shared with accountants at Marcum. The Times and Marcum used income, deduction, family size and filing status from those returns and applied major elements of the tax plans approved by the House and Senate to compile two estimated tax bills for each filer. If the House and Senate agree to a reconciled tax plan that is signed into law by President Trump, the changes would take effect in 2018 and not affect tax returns for the 2017 tax year.

Follow me: @jrkoren

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.