Co-founder feuds at L.A. tech start-ups show how handshake deals can blow up

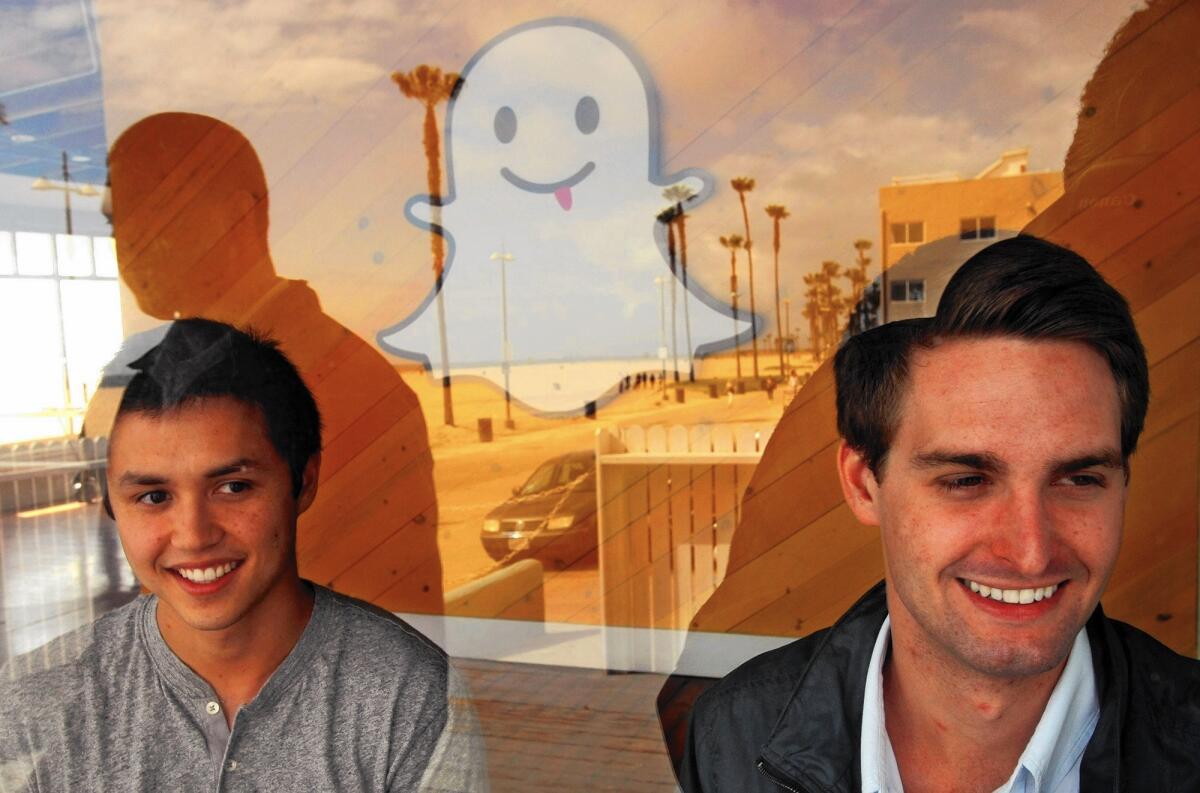

Bobby Murphy, left, Snapchat’s chief technology officer, and Evan Spiegel, chief executive. In 2013, co-founder Reggie Brown sued his former colleagues and venture capitalists, alleging breach of contract.

- Share via

Two Stanford University undergraduates shook hands in their dormitory in early 2011, agreeing to partner on what they hoped would be the next big technology start-up.

But as their dream came true, their simple exercise of trust became a liability when one co-founder was dumped. A flimsy foundation of oral OKs, napkin scribblings and youthful haste, it turns out, is a dangerous mix. And a common one.

Snapchat Inc., the Stanford residence hall creation that later moved to Venice Beach, is on a growing list of hot start-ups that have faced bitter lawsuits or wrenching behind-the-scenes battles over who played an essential role in a company’s birth and how much money and respect they deserve as a result.

Co-founder disputes are common in the business world, whether in television production, restaurants or real estate, lawyers say. But the staggering sums at stake for early employees when a technology company becomes a worldwide hit push the industry’s drama to the top of pop culture.

The blockbuster movie “The Social Network” highlighted Facebook’s internal drama. Twitter’s squabbling inspired a book, “Hatching Twitter.” As the Los Angeles tech economy strives to mirror Silicon Valley’s success, it’s producing its own tales of woe, with strife at Snapchat, Tinder, Maker Studios and Beats Electronics providing early chapters.

“As Silicon Beach businesses grow and become more successful, you’ll definitely see more co-founder disputes,” said Luan Tran, the Los Angeles attorney who brought the co-founder case against Snapchat.

Attorneys, venture capitalists and other technology leaders in Los Angeles hope the trend toward disruptive disagreements ends soon. With all the publicity about co-founder disputes, they say there’s no excuse for ending up in a lawyer’s conference room across from a onetime friend.

“Entrepreneurs are so psyched about their product and business that they don’t think about the worst case,” said Amir Hassanabadi, who represents 15 start-ups as an attorney at Fenwick & West. But founders must spend time and some money to set a company’s “bedrock,” he said.

According to Tran — who is embroiled in another co-founder squabble involving anonymous message board app Yik Yak — a common denominator underlies nearly every dispute: The co-founders are friends or family, and they expect the close relationship to substitute for a binding business contract.

“You don’t think not to trust people you know a lot, and you don’t think they are going to screw you,” Tran said. “It’s good to trust, but it’s much better to memorialize your trust in a document.”

Plenty of entrepreneurs have not, judging by the calls Tran has received since filing the Snapchat case two years ago. He recently signed two clients who plan to bring co-founder cases, and two new inquiries a week arrive from co-founders considering lawsuits, many in Los Angeles, compared with a call once every three or four months and rarely one from Los Angeles before.

That’s because Los Angeles is emerging as a world-class center of technology. It’s also because of the nature of start-ups in an app economy, where an item can go viral overnight with little financial investment.

The Snapchat situation, as laid out in a lawsuit by jilted co-founder Reggie Brown, began when the English literature major told product design student Evan Spiegel, now Snapchat’s 24-year-old chief executive, about an idea in which people could share a photo that quickly self-destructs after viewing. They recruited a third partner, Bobby Murphy, who remains Snapchat’s chief technology officer, to do the computer programming. An oral agreement cemented their triumvirate.

But soon after, Spiegel decided that Brown’s abilities didn’t measure up, according to Spiegel’s deposition. Spiegel and Murphy locked Brown out of the company’s systems and disavowed him.

As Brown worked an unpaid position elsewhere, Snapchat received $1-billion-plus takeover offers from Facebook Inc. In February 2013, Brown sued his former colleagues and venture capitalists who helped fund Snapchat’s development, alleging breach of contract. They reached an undisclosed settlement last summer. Tran and Snapchat declined to comment.

The disagreements are almost always precipitated by some climactic event involving money — either receiving a lot of it, as in the case of Snapchat, or running out of it, as in the case of Ari Rashti and his company SafeSoft Solutions Inc.

In 2006 as a senior at USC, Rashti teamed with three acquaintances to create software for call centers that analyzes voice data to decide when to connect an agent. He wanted to sign more customers before developing new features. But two of his co-founders opted to burn through cash on computer programmers. Two years in, Rashti quit rather than see the Woodland Hills company fold over the discord.

“It took us a while to get to a final agreement, and still no one is ... past resentment,” said Rashti, who regrets writing the company’s founding documents himself rather than seeking more outside counsel. “Not everyone’s on their merry way.”

Nima Hakimi, a SafeSoft co-founder and its CEO, said they could have avoided the trouble by setting goals besides “Let’s make money.”

“You can’t plan everything, but there should be some common understanding over where you want to go and by when,” Hakimi said. “As much as you can, manage based on objectives.”

SafeSoft weathered the disruption and now has about 15 workers and millions of dollars of annual revenue, Hakimi said. Rashti started his own digital marketing agency, ReDesign Digital.

When Tim Sae Koo started his company Tint, advice from a lawyer prevented some headaches during a co-founder divorce. Sae Koo graduated from USC a semester early in 2011 so he could work full time on a class project that evolved into an app for companies to display social media content.

The team of five founders — including Willy Wang, Sae Koo’s friend since elementary school — disagreed on their sales strategy and whether to move from Wang’s parents’ home in Arcadia to office space in San Francisco. In some cases, their skills overlapped, causing unnecessary duplication on such a small team.

Wang decided to quit, and another co-founder left soon after because of a separate conflict. Both still hold shares in the company.

The early legal assistance, which Tint didn’t pay for until it raised venture capital, saved Sae Koo from a nightmare. But he still acknowledges making a “rookie mistake” by hiring too many people too fast.

“I just thought more people equals a stronger team … and more opportunity to succeed as a business,” Sae Koo said.

Veteran venture capitalist John Morris, who also runs a management consulting firm, says too many co-founders can result in “three musketeers” who each feel entitled to more power than they deserve. A co-founder designation holds no legal significance, and its cultural definition is somewhat arbitrary. But investors and customers afford more credibility to “co-founders” because it suggests an appetite for risk and a mind full of ideas.

It’s “the naive” who award the title and “the smart” who push for it because of its value on a LinkedIn profile, Morris said.

Whitney Wolfe sued the dating app Tinder after Chief Executive Sean Rad wrote to her that she could call herself a co-founder, but then allegedly changed his mind a year later. The suit was settled in September. Wolfe still describes herself as a Tinder co-founder as she runs a competing dating app, Bumble.

Beats Electronics in September sued Steven Lamar, the founder of competitor Roam who called himself a Beats co-founder. He’s removed that title from online profiles and is seeking a dismissal.

Maker, a Walt Disney Co.-owned online video studio, was sued by four founders who allege that their power was fraudulently stripped by two founders and several board members who wanted to quickly sell off the company. This month a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge ruled against most of the plaintiffs’ claims.

Hassanabadi, the attorney, says newer clients have read the news about these cautionary tales. Still, he makes a stern request to co-founders on Day One: Go out for dinner, settle who’s who and what’s what. Then put it in writing.

Twitter: @peard33

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.