How Harvey Weinstein used his fashion business as a pipeline to models

It was the kind of evening Zoë Brock was accustomed to, an intimate dinner party at an Art Deco hotel on a waterfront avenue in Cannes. The Australian model was ushered to an empty seat at a long table on a lush patio overlooking a swimming pool.

She didn’t recognize the man seated next to her, but would quickly find out he was Harvey Weinstein, a brusque American producer in town for the film festival.

That first encounter of champagne and small talk would end in a much less elegant fashion hours later in a hotel room, where Weinstein stood before Brock naked and solicited a massage. She said she locked herself in a bathroom to escape him.

Still shaken by that night in 1998, Brock believes the events were set in motion by men connected to Weinstein.

“Someone put me there next to him — that was on purpose. I am pretty sure that there are a lot of people that would like to sit next to Harvey Weinstein,” said Brock, 43, who was represented by a Milanese modeling agency at the time. “So why was it me?”

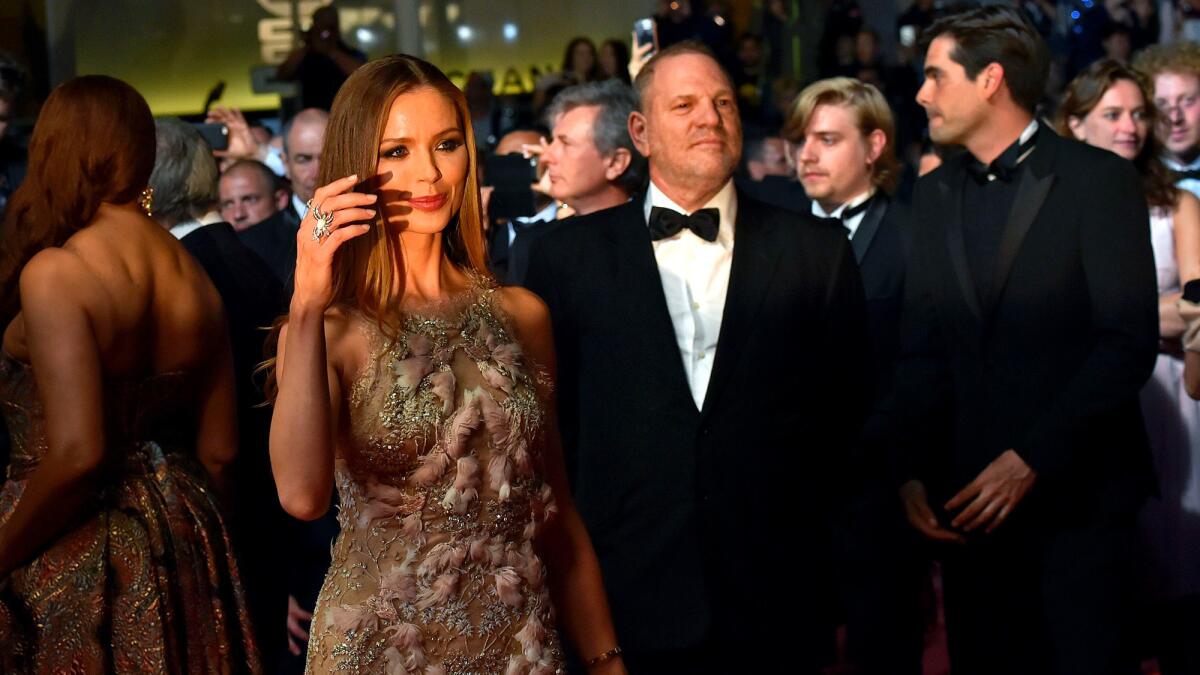

Weinstein, 65, is best known for his pioneering career in the independent film industry, but over the last two decades he has also carved out a significant business in fashion — executive producing the television show “Project Runway,” investing in the clothing brand Halston, and backing the high-end womenswear company Marchesa, which was co-founded by his wife, former model Georgina Chapman. The foray generated a profitable TV franchise, lucrative partnerships and cachet among the global jet set.

But that success was only one of the benefits for Weinstein. In interviews with the Los Angeles Times, nearly a dozen people with ties to the industry — including models, casting directors, publicists and executives connected to “Project Runway” — said that he used fashion as a pipeline to women. They said that models, oftentimes young and working overseas far from home, were particularly vulnerable.

In addition to Brock, more than 10 other former or current fashion models — including Cara Delevingne and Angie Everhart — have accused Weinstein of a wide range of sexual misconduct.

In a previously unreported incident, former Brazilian model Juliana De Paula told The Times that Weinstein groped her and forced her to kiss other models that he had taken to his loft in New York a decade ago. When she tried to leave, she said, he chased her through the apartment, naked. She fended him off with a broken glass.

“He looked at me and he started to laugh,” she recalled. “I was shocked. I was completely in disbelief.”

Another model, Samantha Panagrosso, said Weinstein made unwanted sexual advances toward her during the Cannes Film Festival in 2003. When Weinstein began touching her legs under the water at a hotel pool and she rebuffed him, he pointed at another model, she recalled in an interview with The Times. “Look at her, I’m going to have her come to my room for a screen test,” she said Weinstein told her.

When Panagrosso told friends about his continuing advances, she said, they laughed it off: “Sam, don’t be so naïve, you know Harvey can make you a star.”

Since the New York Times and the New Yorker first wrote about Weinstein’s alleged assaults earlier this month, more than 50 women have come forward to describe their experiences, and he has been fired by Weinstein Co., the indie studio he co-founded in 2005 that has released films including “The King’s Speech.”

Six women have accused Weinstein of rape or forcible sex acts, and he is under investigation for sexual assault in Los Angeles, New York and London.

Weinstein has entered counseling and apologized for some of his behavior. But, through his spokeswoman Sallie Hofmeister, Weinstein has “unequivocally denied” any allegations of nonconsensual sex. As for the accounts of Brock and Panagrosso, Hofmeister said, “Their recollection of events differs from that of Mr. Weinstein.”

Becoming a fashion fixture

Weinstein’s transformation into a fashion player was an unlikely turn for a movie producer at the zenith of his career.

By 2000, films released by Weinstein’s company, Miramax, had collected dozens of Oscars, including best picture awards for “The English Patient” and “Shakespeare in Love.” Weinstein had garnered a reputation for his bullying tactics and aggressive Academy Awards campaigns in pursuit of the gold statuette that burnished his reputation as a kingpin of prestige films.

He was also among a growing wave of major movie producers to expand into television. His “Project Greenlight” documented the travails of would-be filmmakers and made a splash when it launched on HBO in 2001.

Also around this time, the fashion world was being buffeted by change. Glossy magazines, such as Vogue and Elle, were putting A-list Hollywood actresses on their covers because they helped sell more copies than lesser-known fashion models. For high-end magazine publishers — and for models aspiring to break into Hollywood — Weinstein had the right connections.

And he thrived on being at the nexus of culture.

“For these powerful people, the most seductive currency is the one they do not own,” said a current business associate of Weinstein. “He used his Hollywood connections, which reflected well in fashion and in television — and even politics.”

It wasn’t long before the former fashion novice was just as much a fixture at New York Fashion Week as he was on the red carpet of Hollywood movie premieres.

Interviews with six people connected with Weinstein’s cable television show “Project Runway” help shed light on his fascination with fashion. These individuals declined to be identified, partly because of ongoing business ties to the Weinstein Co.

They said the success of “Project Greenlight” had increased Weinstein’s appetite for television — and what he wanted more than anything was a program that featured fashion models.

Weinstein’s spokeswoman said that “Project Runway” was developed as a replacement for “Project Greenlight,” which was ending its run — and not as a vehicle to meet women. He simply thought it was a good idea for a television show, Hofmeister said.

In the foreword of the 2012 book “Project Runway,” Weinstein wrote that he has “always been intrigued and inspired by the creative process.”

“I have learned along the way that talent can come from anywhere,” he wrote.

In the early 2000s, Weinstein introduced his Miramax executives to a German fashion model, Daniela Unruh, who was in her early 20s at the time, saying she had an idea for a reality show. Unruh pitched a program called “Model Apartment,” which would follow a group of models living together.

Executives were skeptical that such a show would be compelling, but optioned Unruh’s idea for a token amount — about $8,000, according to one former Miramax employee. Unruh receives modest royalties from “Project Runway.”

Her concept was retooled to focus on fashion designers competing for their big break. Development of the show gained traction when supermodel Heidi Klum signed on, but the process was slow — and Weinstein was growing impatient.

“He kept asking: ‘Where’s my model show?’” recalled a former employee. “He wouldn’t drop it.”

Fearful of Weinstein’s reaction — because the show featured designers with sewing machines and not models — the producers figured they needed to amp up the participation of beautiful women. The producers concocted an awkward competition within the show that allowed designers to pick the model they found most appealing, which resulted in aspiring models, occasionally in tears, being dismissed.

“That was designed as a vestigial element for Harvey,” the television executive said.

“Project Runway” launched in 2004, and over the course of its 16-season run, more than 200 models have appeared, according to the Internet Movie Database.

The hit program grew into one of Weinstein’s most lucrative franchises. He leveraged its popularity to land a huge $150-million, five-year deal in 2008 with Lifetime, where he moved the show from Bravo.

And he eventually got his model-themed reality show on Lifetime: “Models of the Runway,” which lasted just two seasons.

But after dozens of women came forward this month to discuss Weinstein’s alleged misconduct, his name was quickly stripped from the credits of “Project Runway.”

Deepening fashion ties

The same year that “Project Runway” debuted, Weinstein met his future wife.

Weinstein encountered Chapman, a British model and costume designer, at a party in New York in 2004, not long after he split from his first wife, Eve Chilton Weinstein, according to various published reports. Weinstein was in his early 50s and Chapman in her late 20s when they began to date.

That year she also co-founded the Marchesa fashion brand with Keren Craig, her longtime friend and classmate at Chelsea College of Art and Design. Weinstein worked behind the scenes to help them launch their label — again expanding his reach deeper into the fashion world.

Vogue was soon featuring the New York-based company’s clothes in its pages. Weinstein also asked actresses to wear Marchesa gowns to big award shows and events.

Within months, Renee Zellweger, fresh off winning a supporting-actress Oscar for “Cold Mountain,” strolled the red carpet in a strapless Marchesa dress at the London premiere of the Miramax-distributed “Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason.” A procession of Weinstein-connected stars soon followed, among them Cate Blanchett, Scarlett Johansson and Felicity Huffman.

Marchesa’s meteoric rise raised eyebrows — and questions about what accounted for it.

“Marchesa’s breathtaking success has the fashion world talking — and rolling its eyes too. Just how much of that success, observers wonder, is due to the Harvey Factor?” a Los Angeles Times article asked in 2006, a year before Weinstein and Chapman wed.

Competitors complained that stars wore Marchesa on the red carpet because they — and their agents, managers and lawyers — needed to please the powerful Weinstein.

“Now we have Harvey Weinstein married to the designer, who is able to put her dresses on … anybody in Hollywood,” said Julia Samersova, a former modeling agent who works as a casting director in New York. “Yes, it is really that simple. Who is going to say no to the wife of Harvey Weinstein?”

This week, amid the rapidly unfolding sex scandal, the actress Huffman confirmed, via her publicist, that Weinstein did demand that she wear Marchesa gowns at public appearances. But the publicist denied reports that he had threatened to withhold funding from her 2005 movie “Transamerica.”

Chapman, in an interview for the 2006 Times story, laughed off any suggestion that Weinstein was Marchesa’s guiding force. “If anybody looks at how Harvey dresses, they realize he doesn’t have terribly much to do with designing,” she said.

Neither Chapman nor Craig responded to requests for comment.

In 2007, Weinstein expanded his fashion holdings: Weinstein Co. and Hilco Consumer Capital bought Halston, the once-venerable American fashion house that had fallen on hard times. Weinstein became a member of the company’s board, and Jimmy Choo co-founder Tamara Mellon and actress Sarah Jessica Parker also got involved in the revival effort. But Halston soon foundered, and Weinstein departed the venture in 2011.

Some in the business, like Fern Mallis, the former executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, have now sought to downplay Weinstein’s role in the industry — while also expressing support for Marchesa’s founders.

“I’m appalled like everyone else about his behavior and support all the brave women speaking out,” Mallis said. “He was not an ‘influence’ in the fashion industry, and I feel very bad for Georgina and Keren, who are very talented designers and built a terrific business with Marchesa.”

Other industry power players with ties to Weinstein have also denounced him, including Vogue editor Anna Wintour, and designer Tom Ford, whose 2009 film “A Single Man” was distributed by Weinstein Co.

Chapman, 41, announced last week that she was leaving Weinstein and would focus on caring for their two children.

A pipeline to models

While the fashion industry proved lucrative for Weinstein and burnished his reputation as a tastemaker, it also filled his world with even more young, beautiful women.

Several women who have publicly accused Weinstein of misconduct described incidents in which he used his fashion business ties and ownership of “Project Runway” as enticements or pretexts for meetings.

Former aspiring actress Lucia Evans told the New Yorker that Weinstein said during a meeting that she’d “be great in ‘Project Runway’” before allegedly forcing her to perform oral sex. Model Ambra Battilana Gutierrez’s 2015 meeting with Weinstein began with discussions of her working as a lingerie model before he allegedly grabbed her breasts and put his hand up her skirt, according to the New York Times.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, a television actress claimed that when she rebuffed Weinstein’s advances about a decade ago — saying that she had nothing suitable to wear to events he wanted to take her to, including the Cannes Film Festival — he would tell her that he could deliver 10 Marchesa dresses.

Separately, a former British model said that when Weinstein was pursuing her about a decade ago in London, he persuaded her to switch modeling agencies to a higher-profile one where he had connections. She also said he suggested he could help her launch an acting career. “The whole thing was a control thing,” said the woman, who spoke on the condition of anonymity over concerns about repercussions from discussing the matter.

This sort of behavior is not new to the fashion and entertainment industries, which are plagued by a culture of exploitation, said Victoria Keon-Cohen, a model who spearheaded a unionizing effort a decade ago in London and is now a filmmaker.

“There’s a very dominant feeling of favors for work,” she said, adding that this is especially the case in fashion, where “very vulnerable young girls and boys are trying to advance their careers.”

An encounter in Cannes

Brock, the fashion model from Australia, traveled to Cannes in 1998 at the invitation of her Italian agent. Fresh off of working Paris Fashion Week, Brock, then 24, was eager to network.

Over dinner at the Majestic Hotel, Brock said, she and Weinstein had “a really good conversation,” chatting about a mutual friend — a female director whose film Miramax had recently distributed. “It felt like Harvey was family,” she said.

Eventually, some in the dinner group made their way to the Hotel du Cap Eden-Roc, a luxury property 30 minutes away where Weinstein had a suite. Brock said she soon found herself alone in the room with Weinstein.

Before long, Weinstein was naked and pleaded with her for a massage, Brock said. When she declined, Brock said, he asked to give her one. “I relented and let him touch my back and shoulders,” she said. “But I couldn’t handle his hands on me, so I bolted out of there, and bolted into the bathroom and locked the door.”

She still had to ride back to Cannes with Weinstein. On the way, an apologetic Weinstein offered to make Brock “a star” and be her “Rock of Gibraltar,” she said.

That night, she called her mother and actor Rufus Sewell, who stars on Amazon Studios’ “The Man in the High Castle,” to tell them what had occurred. Both confirmed speaking that night to Brock and hearing her account.

When she finally made her way back to the yacht where she was staying around 5:30 a.m., she said, she felt — and looked — like “a whore.”

“I was wearing yesterday’s dress, with yesterday’s makeup, and messed hair,” she said. “Having to crawl back into the boat looking like that made me look like the sort of person who would have slept with Harvey Weinstein to further my career. And I am not that person.”

‘This is not going to be fun at all’

Nearly a decade later and halfway around the world, another former model experienced an upsetting encounter with Weinstein.

One night in 2007, De Paula and some model friends were introduced to Weinstein during a karaoke party at the lounge above Cipriani Downtown, a buzzy Italian restaurant in Manhattan.

Soon, a plan was hatched to go to Weinstein’s loft in Soho, said De Paula, who previously modeled in Brazil and has since had other jobs in fashion, including as a manager of a photography studio in New York.

Once Weinstein, De Paula and three models were inside the elevator, he began fondling the women’s breasts and making them kiss each other, De Paula said. “Forcing. Like putting both heads together,” she said.

She said the women tried to resist, but were “embarrassed” and unsure of how to fend him off. The elevator opened inside Weinstein’s residence, and he began disrobing. “My [alarm] bells rang,” she said. “It was, oh my gosh, this is not going to be fun at all.”

De Paula said that Weinstein ushered the three models into his bedroom, but she ran into the adjoining bathroom. She heard at least one woman yell “stop” multiple times, but didn’t have a clear view of the bedroom.

After a while, De Paula said, she fled the bathroom, ran through the bedroom and into the kitchen. A nude Weinstein followed her there, she said.

“He was moving toward me. I got scared, and I was afraid,” De Paula said.

She reached for a wine glass, broke it, brandished it, and gave Weinstein an ultimatum: “You let me out of here right now, or this is going to have serious consequences.”

She said Weinstein, laughing, asked, “Are you serious?” before allowing her to depart.

The next day, De Paula told her then-roommate about the alleged episode with Weinstein. The roommate told The Times that he remembered the conversation, recalling a “distressed” De Paula describing the events at Weinstein’s loft.

“Mr. Weinstein says the story is a fabrication,” said Hofmeister, Weinstein’s spokeswoman.

A few months after the alleged incident, De Paula went to a Dec. 5 concert at Cipriani Wall Street where Aretha Franklin performed. Weinstein’s attendance was noted in a press release recapping the event.

“He came up to me, super nice — it seemed like it was somebody else,” said De Paula, who now lives in Brazil. “I didn’t have the courage to look at him. I looked down.”

Weinstein asked for her phone number. She declined.

Fashion looks inward

As with Hollywood, the Weinstein scandal has prompted the fashion industry to ponder how women are treated and whether it is doing enough to protect vulnerable participants.

Several people interviewed for this article acknowledged that Weinstein had, for years, a poor reputation in the fashion business, but little if anything was ever done to spotlight this. Some are hoping for big changes. On Tuesday, the Model Alliance, a nonprofit trade group, issued a statement saying, “No person should tolerate any sort of unwanted or inappropriate conduct, nor should our industry.”

Brock said that she hopes her personal story about Weinstein might help spur change in the business.

“I hope that from this moment on, young girls, from every country, start to value themselves as more than the objects the industry has always treated them as,” she said.

Staff writer Victoria Kim contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.