Column: Labor Dept. finally closes a loophole favoring union-busters — after 57 years

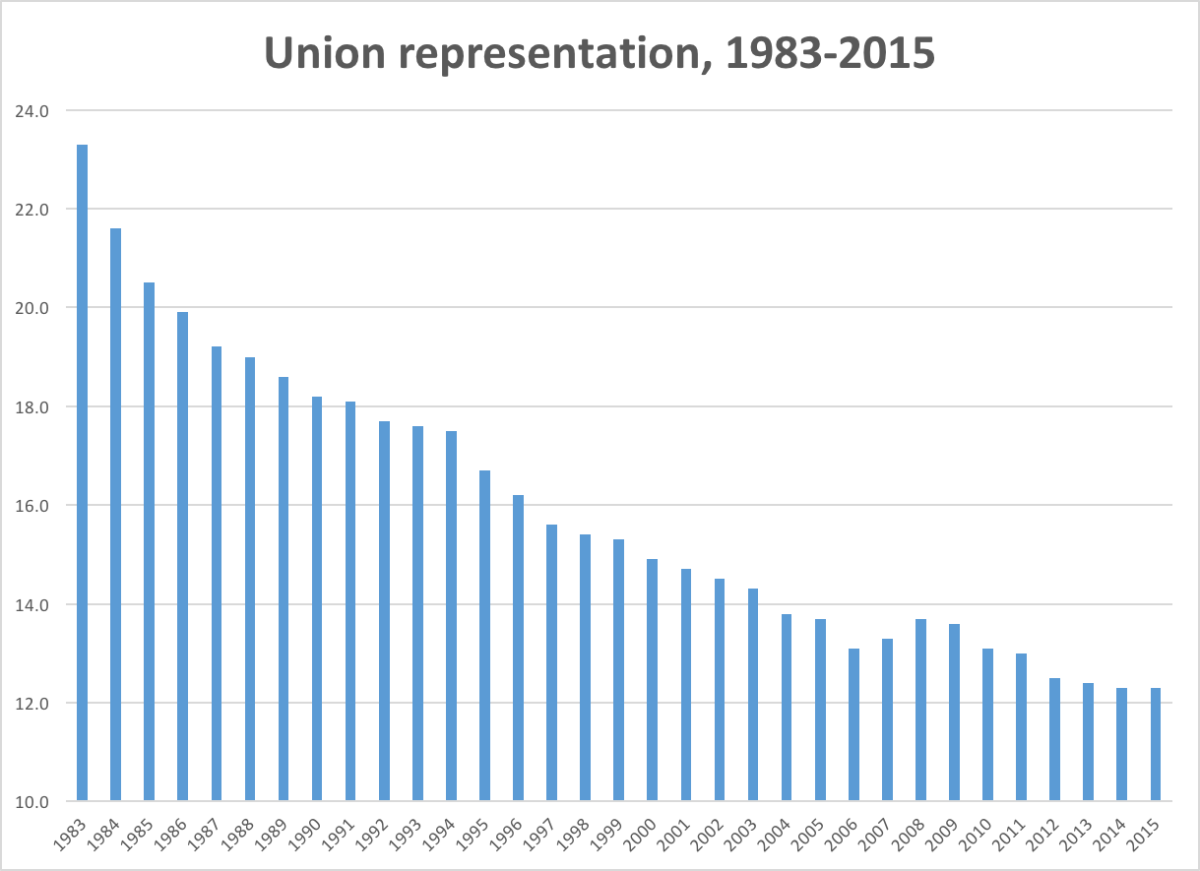

Explanations abound for the consistent decline of organized labor in the United States, especially in the private sector. But one important factor is the ability of employers to engage in union-busting almost without restriction.

Limitations on employers' activities exist, theoretically, but they've been enforced only spottily and are rife with loopholes. The Dept. of Labor finally has moved to close one loophole, created way back in 1959. This is the ability to hire anti-union consultants, familiarly known as "persuaders," without reporting the arrangements. The Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959, otherwise known as the Landrum-Griffin Act, required these deals to be reported only if the consultants were speaking directly with employees, but not if their influence reached the workplace floor indirectly, via intermediaries.

I come from a very dirty business.

â Former professional union-buster Martin Jay Levitt

In the opinion of a close observer, that was one of the "enormous, gaping errors in the law that have left room for a sleazy billion-dollar industry to plod through." The words come not from a union official, but a former union-buster â Martin Jay Levitt, whose 1993 book "Confessions of a Union Buster" should be required reading for every rank-and-file employee in the country. Thanks to the loophole, Levitt wrote, "I never filed with Landrum-Griffin in my life, and few union busters do."

Thanks to the new Labor Dept. rule, that dodge ends as of July 1. The goal is to make sure that when employees interested in organizing with a union are confronted with scripted arguments from supervisors or fellow employees, they know who wrote the script.

"Workers often donât know that their employer hired a consultant to manage its message in union organizing campaigns, including by scripting speeches by managers, talking points, letters, and other documents," the Labor Dept. says in an explanatory note. "Consultants may also direct supervisors to express specific viewpoints that donât match those supervisorsâ actual views as individuals â something workers may find relevant in assessing the information they receive from their supervisors."

Labor Secretary Thomas Perez cited the "Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain" from "The Wizard of Oz" in lecturing employers about the rationale for the new rule. "If you believe in what an outside expert drafted for you to say to your employees, if you were willing to pay the outsider to help you say it, then open the curtain and reveal who scripted the message and managed its delivery."

Over the years, these hidden persuaders have polished their techniques and their pitch. Typically, a company facing a union organizing drive arranges captive audience meetings characterized as "information sessions" at which the message delivered to employees is that unions are divisive, protect underperformers at the expense of hard workers and are just businesses that only want their dues money but don't really care about their welfare. But, of course, the choice still is the employees'.

In recent years, many of these sessions have been exposed by workers who record them on their smartphones and posted the results. A typical session at FedEx can be heard in the recording here; for this and other such recordings, see this 2014 compilation by Dave Jamieson of the Huffington Post.

These meetings, of course, are only part of the union-busting arsenal. According to a 2009 survey of union elections overseen by the National Labor Relations Board, the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute, "workers were forced to attend anti-union one-on-one sessions with a supervisor at least weekly in two-thirds of elections, ... employers used supervisor one-on-one meetings to interrogate workers about who they or other workers supported, and in 54% used such sessions to threaten workers."

That's not all. "Employers threatened to close the plant in 57% of elections, discharged workers in 34%, and threatened to cut wages and benefits in 47% of elections."

The union-busting business was the brainchild of Nathan Shefferman, an industrial psychologist and "efficiency expert" who hung out his shingle in the 1940s and developed a panoply of subtle and unsubtle anti-union techniques, including "the administration of opinion surveys, supervisor training, incentive pay procedures, ... job evaluations, and legal services," some of which masqueraded as mere management consulting. He also connived with union officials for the latter's own profit, including Teamster President Dave Beck, who went to prison (briefly) for racketeering in 1959.

That was the same year that President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Landrum-Griffin Act, which superficially looked like a fair-labor-practices law â it gave union members expanded access to their unions' finances, for instance â but "gave labor consultants glee," wrote Levitt, by forcing financial disclosures from unions and their officials without balancing regulations of management consultants.

In this atmosphere, Levitt became a disciple of Shefferman's methods. As he detailed in his book, his career in professional subterfuge eventually drove him to alcoholism, once he understood that "a union-busting campaign left a company financially devastated and hopelessly divided and almost invariably created an even more intolerable work environment than before." He renounced the business and turned to advising unions and speaking to union conferences, at which his first words would be, "I come from a very dirty business."

The Labor Dept.'s new rule will at least shine one more light bulb on that business.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.