Column: The Trump plan: Every bad tax idea, in one place

A hop, a skip and a jump ahead of Saturdayâs 100-day benchmark for President Trump, his administrationâs income and corporate tax plan was unveiled on Wednesday.

That might be the right word for it. The unveiling of the headstone is what happens in Jewish tradition a year after the death of the interred. But it wonât take a year to mark the burial site of this corpse: conservatives and liberals alike were picking it apart within minutes of its arrival.

âAmerica canât afford a $5-trillion tax cut,â declared the budget hawks at the conservative Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The CRFB based its judgment on an op-ed published last week by four Trump economic advisors that listed several of the major elements of the plan announced Wednesday.

The top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie.

— Thomas Hungerford, Congressional Research Service (2012)

House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and two other GOP congressional leaders were noticeably lukewarm about the plan in a formal statement Wednesday. While bowing to the Republican shibboleth of lower taxes, they described the elements of the Trump plan merely as âcritical guideposts for Congress and the Administration as we work together to overhaul the American tax system.â Thatâs praise so faint it barely registers on the microphone.

To examine the Trump plan specifically â not an easy task, given its dearth of specifics â one finds that itâs a digest of some of the worst ideas at large in the tax debate. Some lack any historical or economic support, some are transparent giveaways to the rich, and at least one is an openly political swipe at what the White House considers to be hostile (read Democratic) voters.

The plan, which is advertised as an instrument of higher economic growth, would cut the top corporate tax rate to 15% from 35% and allow business owners to pay the lower rate as a âpass-through,â a way of sheltering personal income. The plan also would offer corporations a one-time tax incentive to bring back home income sheltered abroad.

Trump would compress the current seven personal income tax brackets, which top out at a 39.6% rate, to three (10%, 25% and 35%), while eliminating all deductions except those for mortgage interest, retirement nest eggs and charitable contributions and doubling the standard deduction.

Also eliminated would be the deduction for state and local income taxes, which would strike hard at residents of such Trump-resistant states as California, New York and Illinois. Trump also would eliminate the estate tax, and a 3.8% surcharge on investment income enacted as part of the Affordable Care Act and devoted to funding for Medicare.

Some conservative economists think the corporate tax cut is the most powerful part of the package; even some progressive economists agree that eliminating corporate loopholes and lowering the statutory rate would be a good thing â if it could be done without expanding the deficit.

âLowering the corporate rate is really going to bear fruit,â says conservative economist Arthur Laffer, one of the coauthors of last weekâs op-ed. He says the cut in the top rate will discourage U.S. companies from relocating in low-tax havens overseas such as Ireland and even encourage overseas companies to move to the U.S.

âItâs not rocket science,â Laffer told me. âPeople move toward the lowest tax rate.â Asked if he believes that the tax package could raise U.S. economic growth by a percentage point per year, as the Trump administration claims, he said, âI think it could be a lot more than that.â

But not all economists agree with that optimistic outlook. Letâs take a look at some of the elements.

1. The flawed notion that lower tax rates âpay for themselves.â This ever-popular Republican rationale for tax cuts, especially those directed at the upper reaches of the income ladder, is based on the conviction that tax cuts invariably spur higher growth, and therefore the revenue loss from lower tax rates will be made up by higher revenue from more and richer taxpayers.

The notion has been debunked in theory and by reality. Thomas Hungerford of the Congressional Research Service, an arm of the Library of Congress, laid out the evidence in a 2012 paper, in which he found no relationship between top marginal income tax rates over the previous 65 years.

âThe top tax rates appear to have little or no relation to the size of the economic pie,â he wrote. Lowering the top tax rates, however, did contribute to increasing income inequality. Hungerfordâs paper infuriated Republicans, who managed to get it withdrawn from circulation.

A year later, Hungerford turned his attention to corporate taxes. He found that, if anything, lower corporate tax rates were associated with lower economic growth. For the most part, however, he determined that there was no correlation.

Conservative economists have been consistently skeptical that cuts pay for themselves. A 2005 paper co-written by N. Gregory Mankiw of Harvard, later to become President George W. Bushâs economic advisor, found that tax cuts paid for perhaps one-third of their initial cost and never for their entire cost. And that didnât count the economic burden of a larger deficit if the tax reduction wasnât balanced by spending cuts.

2. We already tried a tax break to bring home foreign earnings. It failed. In 2004, Congress enacted a one-time amnesty allowing U.S. companies to repatriate earnings parked abroad at a bargain tax rate â 5%, rather than the top rate of 35%. The idea was for them to spend the money on jobs and domestic investment.

Instead, corporations spent the money on stock buybacks to benefit their shareholders and to fatten executive pay. A Senate subcommittee report in 2011 determined that the 15 biggest companies taking advantage of the tax holiday, including Pfizer, Hewlett-Packard and IBM, actually cut jobs and reduced research spending. The treasury lost $3.3 billion in revenue over 10 years, the panel found.

âThere is no evidence that [the tax break] increased U.S. investment or jobs, and it cost taxpayers billions,â a U.S. Treasury report determined. After the tax holiday, U.S. corporations even stepped up their sequestering of profits abroad, figuring that sooner or later a new administration would offer them yet another break â as Trump is proposing. That hoard of what USC business professor Edward Kleinbard calls âstateless incomeâ now tops $2 trillion.

3. The pass-through for business owners Trump advocates for the U.S. has killed the Kansas economy. Trumpâs plan is to allow owners of âsmallâ businesses to avoid the personal income tax by paying the new, lower business tax, a device known as a âpass-through.â This is a linchpin of a tax program that Sam Brownback, the Republican governor of Kansas, has implemented.

For Kansas, itâs been a disaster, encouraging taxpayers of all types to claim ownership of a business in order to avoid the personal income tax.

The pass-through is a major reason for a sharp drop-off in Kansas tax revenue, experts say â in 2013, for instance, revenue âdropped by $700 million ($300 million more than predicted),â according to Scott Drenkard of the Tax Foundation. Desperate to fill the ever-widening hole in the state budget, Brownback has cut spending on state services and delayed a sales tax cut â making the stateâs tax system ever more regressive.

The pass-through is an invitation to tax manipulation. âIf they passed a provision like this in Washington, D.C., where I live and work, I would benefit from going to my employer the next day and ask them to start paying me as an independent contractor,â Drenkard told Kansas legislators in January. âI would still be doing the same job and contributing the same value to the economy, I just wouldnât be paying any income taxes.â

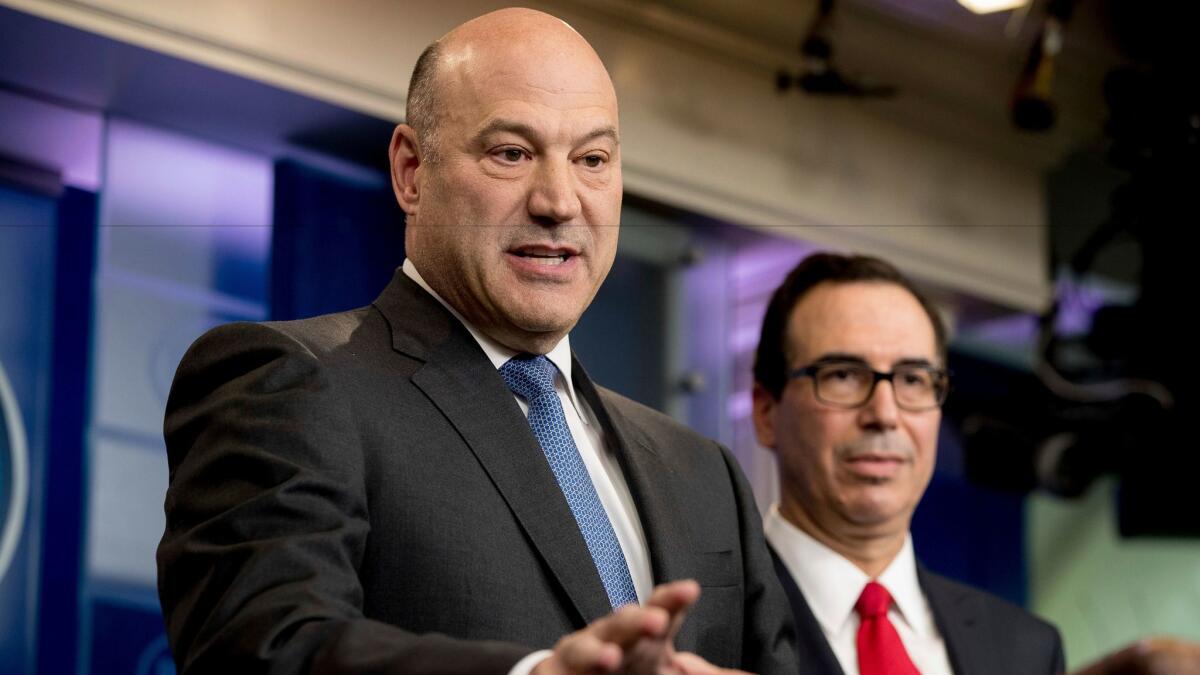

Although the pass-through is billed as a boon to small-business owners, in fact it would apply to owners of rich businesses structured as partnerships and sole-proprietorships, such as law firms and companies structured like the Trump Organization, the presidentâs business. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin says the White House has ideas to limit its abuse, but didnât mention specifics on Wednesday.

4. Killing the estate tax is a handout to the rich. Long rebranded as the âdeath taxâ by conservatives, the estate tax largely affects the richest Americans while perpetuating the development of aristocratic wealth that was abominated by some of the founding fathers, including Thomas Jefferson and Ben Franklin.

Trump during the campaign called the estate tax a burden on the âAmerican worker.â Yet the estate tax affects only a few thousand people at most, all of them multimillionaires with an average nest egg of more than $30 million. Currently, the tax is set at 40% of estates, with an exemption worth $5.49 million per individual and $10.9 million per couple.

Bowing to the power of the rich, Congress eliminated the estate tax entirely for 2010â the suspension was pushed by Sen. Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.), whose state hosted armies of well-heeled retirees, and Sen. Blanche Lincoln (D-Ark.), whose constituents including members of the Walton family (heirs to the Wal-Mart fortune). The tax was restored in 2011, leaving behind only a âLaw & Orderâ episode about rich families plotting to kill off their elders during the moratorium.

But the repeal movement lives on, fueled by the recurrent claim that the tax burdens small family businesses and farms with an unaffordable bill when the founders pass on, forcing them to sell. Real-life examples, however, are uncommon. Family farms can be valued for estate tax purposes as working farms, not as real estate, which cuts their tax liability sharply. The tax on most farms and businesses, moreover, can be paid over as much as 15 years.

Who would benefit from repeal? Owners of big family businesses, such as the Trump clan.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzikâs blog.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.