The remixed fairy tales of Mallory Ortbergâs âThe Merry Spinsterâ

Call Cinderella Paul.

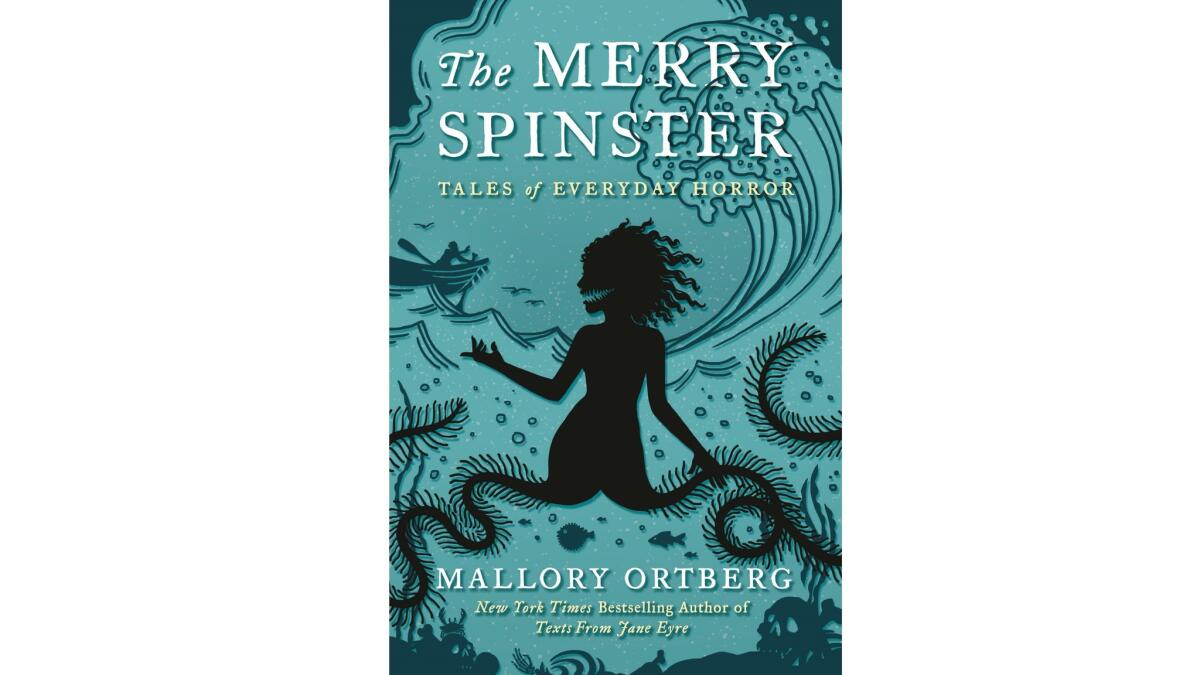

Mallory Ortberg, co-founder of the dearly departed feminist website The Toast, Slateâs âDear Prudence,â and the author of âChildrenâs Stories Made Horrificâ and âTexts from Jane Eyre,â turns beloved fairy tales on their heads in the new short story collection: âThe Merry Spinster: Tales of Everyday Horror.â

In âThe Merry Spinster,â Ortberg remixes âCinderella,â âBeauty and the Beast,â âThe Little Mermaidâ and more well-known sources into stories both weirder and yet somehow more familiar. Beautyâs mother, for example, is a high-powered executive with investment woes, and as the Little Mermaid discovers upon becoming a girl, there are many disadvantages to being human, including âone-way joints [and] a sudden and profound sense of isolation.â Ortbergâs tales are all the more enchanting â and humorous, and haunting â for falling so close to home.

Certain themes reappear throughout the collection, including explorations of gender. In âThe Thankless Child,â Cinderella is named Paul; in âThe Frogâs Princess,â a beautiful daughterâs gender pronouns are he/him. This exploration is personal: half-way through the writing of âThe Merry Spinsterâ Ortberg began attending gender therapy. Ortberg talked to me about transitioning while writing the book, how tough it is to define satire and the epic sadness of Hans Christian Andersen.

Orbertgâs book tour launches Saturday at Skylight Books in Los Angeles at 5 p.m. Our conversation has been edited.

Youâve been described as a satirist. Is there any oblique link between satire and fairy tale?

Probably? This is one of those moments when Iâm really aware of my own limitations, because I think, âDo I know exactly what a satirist is?â If you were to ask me, âCan you clearly and simply lay out the differences between humor, parody and satire?â I would try to jump out a window just to get away, because I straight-up donât know. Satire feels like a sending up of something, and thatâs not the type of work I do most often. I donât feel like this book is satirical in the sense of setting out to subvert or send up or critique any one particular idea. It felt more like an exploration of horror in a very specific context. Satire comes from a position of confidence as opposed to the way that writing this book felt, which was, âOh, Iâm anxious and afraid.â

In these âTales of Everyday Horror,â your riffs on âThe Velveteen Rabbitâ and âThe Wind in the Willowsâ in particular both got me good. Thereâs this terrible feeling of âwith friends like these, who needs enemies?â

Itâs that sense of âCan you trust your own instincts? Can you trust your own read of a situation? To what degree are you responsible for your own well-being and to what degree can you ask other people to safeguard you?â I wanted to explore what that looked like in the context of friends and family. A lot of the book asks: What does it mean to not recognize something that youâre very familiar with? What does it mean to be around something constantly and not know it? What would that make your daily life look like and in what ways would that make your own life essentially unbearable to you?

You began transitioning while writing this book. What is your preferred gender pronoun?

I havenât yet rolled out the name and pronoun change, but itâs going to be a male name and male pronoun. In the meantime, either she or they. I feel like Iâve come out before making the full switch, so thereâs this sense of âIâm out, but keep watching for the skies for updates!â Iâm aware that everyoneâs asking this question: What should we do in the meantime? And my answer has mostly been, âGreat question! Not sure!â

How did the writing of the book and your transition intersect?

I feel like weâve already talked about it in the sense of anxiety and fear and panic. One of the things that I was anxious about was that I wasnât sure if Iâd be out by the time the book was finished. Part of me was really stressed out about the idea of going on book tour and hearing, âHey, thereâs a lot of stuff going on with gender in your book: Whatâs that about?â and having to half answer, like, âYes, isnât gender interesting? Nothing personal going on here!â So itâs been a huge relief just to be able to talk about that as part of the context of the book.

In âThe Frogâs Princessâ you write that âbeauty is never private,â an observation that has chilling ramifications in the story. Whatâs going on there?

There are so many different ways in which, especially for girls, other people will let you know when your childhood is done. It has to do with physical beauty; it has to do with looking queer, so many different things. People will say things like, âThis person is really beautifulâ as if that were a good and a fun thing to say to somebody else. You have ceded ownership of your own image and own body by looking a certain way, and thatâs traumatizing a lot of the time.

Obviously, there are also a lot of privileges that come with beauty, but I was just thinking of a lot of the people that Iâve known in my life who have been told that they were beautiful in various ways, many of which were violent and painful and deeply damaging to oneâs sense of independence. Having that done to you and then being told âthis is good, this is a favor, you should be grateful for thisâ is painful in such a specific way. Sometimes other people will use the word beauty as way of saying, âI want to hurt you. I want to hurt you and I donât want you to know that youâre being hurt so Iâm going to call it beauty.â

Reading âThe Merry Spinsterâ I thought often of Angela Carterâs âThe Bloody Chamber.â What were your literary influences?

Shirley Jackson is another obvious influence here. I read âWe Have Always Lived in the Castleâ for the first time when I was 16. I was in a bookstore and I stood there and read half of it. Then bought it and was just like, âOh, Iâm changed at a cellular level now.â I think also âThe Pilgrimâs Progressâ by John Bunyan. Thereâs so much in it that has to do with what I would call âreligious horror,â which I probably should have gotten from Flannery OâConnor, but Iâve barely read Flannery OâConnor. I just know sheâs what comes up when people talk about comedy and horror and religion.

Both of your parents are ministers. Did Bible stories play a subconscious role in your thoughts about the book?

Very much so, and my conscious thought too, frankly. I have that little bit in the end where I clarify what liturgical or theological sources influence each chapter. The liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas Aquinas and the Desert Fathers all pop up throughout the book. That felt like a very natural and exciting to get to do.

Did you have a favorite fairy tale growing up?

The Andrew Lang Fairy Book collectionsâ âSnow-White and Rose-Red,â and anything by Hans Christian Andersen, who was just so distressing. That man was just sadder than anyone who ever lived. He invented Pixar 100 years early but his version of Pixar was just, âWhat if every object in your home was desperately sad and wanted a soul more than anything else in the world and wanted to go to heaven and was in love with the poker over by the fireplace but they could never touch because they canât move, wouldnât that be terrible?â And itâs just like, âYes, Hans, it would be. These are very sad stories. I am very sad now.â

Your book is clearly for adults, but itâs also unequivocally a book of fairy tales. Itâs satisfying to discover that at every age these archtypical stories matter.

Iâm right there with you. Not to put too fine a point on it, but thereâs this idea that as Iâm writing this book Iâve also entered a second puberty, and thereâs something hilarious about that. This is not what I expected in my 30s, and yet here I am. Which is not to say that thereâs any sense of regression â itâs not that Iâm returning to a lost adolescence â thereâs a powerful sense of experiencing something I have done before in a very different way, and itâs familiar and itâs totally alien and itâs not like anything else Iâve experienced and itâs also a lot like any other change. Itâs not like I thought, âAh ha! Because I am transitioning I will do this book now!â but rather that you donât always know when childhood has let you go, and you donât always know when adulthood is coming for you and you donât always know when oneâs going to call your name.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.