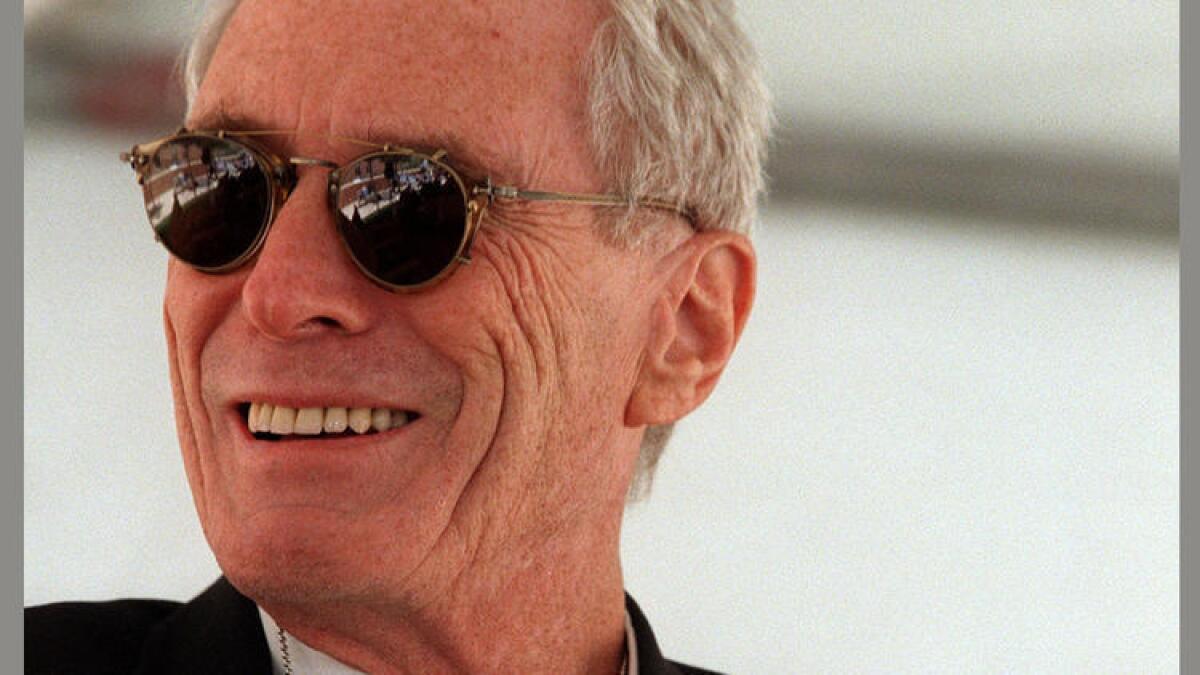

Mark Strand, a revelatory poet of love and death

One of the many clichĂŠs about poetry is that it is an art with just two subjects: love and death. Mark Strand, who died on Saturday at 80, duly addressed love and death in his poems, but in radically lyrical, revelatory ways.

He was an unconventional poet of love, due to his natural aversion to âearnestâ poetry -- by which he meant the self-absorbed enshrinement of the autobiographical. Yet he could write a love poem as eerily sensual as âSheâ: âHer eyes half-open, she saw the man across the room, / she watched him and could not choose / between sleep and wakefulness. / And he watched her / and the moment became their lives.â A moment of altered mutual perception, as love reinvents time, is as romantic as he would get.

He allowed death freer access. In fact, he welcomed death so readily into his lines that the reaper became a vaguely cheerful figure in the Strandian landscapes. Death rather shyly calls out someone named Strand in 2002âs âMan and Camelâ:

I am not thinking of Death, but Death is thinking of me.

He leans back in his chair, rubs his hands, strokes

his beard, and says, âIâm thinking of Strand, Iâm thinking

that one of these days Iâll be out back, swinging my scythe

or holding my hourglass up to the moon, and Strand will appear

in a jacket and tie, and together under the boulevardsâ

leafless trees weâll stroll into the city of souls.

His early books made their nod to surrealism, but like his close friend, the poet Elizabeth Bishop â surrealism grew out of the music of poetic consciousness itself. In Strandâs case, this meant lyric thought was imagistic, painterly, but also articulated in a voice unlike any other. The monumentality and seeming imperturbability of this singing inner self occasionally gave aspiring poets the impression that Strand was an easy poet to imitate.

The wreckage of these misguided attempts at mimicry can be viewed in and out of writing workshops and derivative chapbooks. How to celebrate originality of this order and intent (âand here the dark infinitive to feelâ) and yet neatly articulate its origins? Iâm saying that, despite the luminous clarity of his words, there is an intentionally unsolvable mystery in the wilderness of each Strand poem.

In the night without end, in the soaking dark,

I am wearing a white suit that shines

Among the black leaves falling, among

The insect-covered moons of the streetlamps.

I am walking among the emerald trees

In the night without end. I am crossing

The street and disappearing around the corner.

I shine as I go through the park on my way

To the station where others are waiting.

⌠That, if anyone suffers, wings can be had

For a song or by trading arms, that the rules

On earth still hold for those about to depart.

--âProem, Iâ (from âDark Harborâ)

It may seem contradictory, but beyond the dream-like elegiac treks through his questioning and dark-lit landscapes â Mark Strand remains one of the funniest poets ever. Anarchical wit runs through his entire oeuvre: his fourteen or so collections of poems, a couple prose books, three volumes of translations (including Rafael Alberti and Carlos Drummond de Andrade), three art books, three books for children and his five edited anthologies. (Strandâs âCollected Poemsâ appeared this year.)

His humor wasnât exactly deadpan, but it was joyfully low-key lunatic:

It was clear when I left the party

That though I was over eighty I still had

A beautiful body --

And, look, somebody left a mirror leaning against a tree.

Making sure I was alone, I took off my shirt.

-- âOld Man Leaves Partyâ (from âBlizzard of Oneâ)

And suddenly we heard the explosion.

A man whoâd been cramped and bloated for weeks

Blew wide open. His wife, whose back was to him,

Didnât turn right away to give everything â

a chance to settle.

-- âXXIII, Proemâ (from âDark Harborâ)

I was in the bathtub when Jorge Luis Borges stumbled in the door. âBorges, be careful,â I yelled.âThe floor is slippery and you are blind.â

-- âTranslationâ (from âA Continuous Lifeâ)

Mark Strandâs awards were bountiful and ever-mounting. He won a MacArthur fellowship, the Pulitzer Prize, the Bolligen Prize and the Gold Medal for Poetry from the American Academy of Arts & Letters. He was poet laureate of the United States. He taught at many universities, most recently at Columbia in New York.

For those of us fortunate enough to have counted him as a friend, the clichĂŠ of the ongoing reincarnation of the poet through his recorded genius, his published poems and prose, is close to true. He did write for the ages, his work is canonical â his voice unparalleled â and reading and rereading his poems does indeed sustain the reader. Almost. Except in the bleak recognition that Mark Strand the man is gone forever from us. But even in this unthinkable loss, he seemed to have planned ahead, as always, in leaving notes to posterity in his poems.

âNo need to rush,â he said at the close of the reading, âthe end

Of the world is only the end of the world as you know it.â

How like him, everyone thought. Then he was gone.

And the world was a blank. It was cold and the air was still.

Tell me, you people out there, what is poetry anyway?

Can anyone die without even a little?

-- âThe Great Poet Returnsâ (from âBlizzard of Oneâ)

Muske-Dukes is the author of several books of poems and novels, as well as professor of English/creative writing at USC and founder of the PhD program in literature and creative writing there.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.