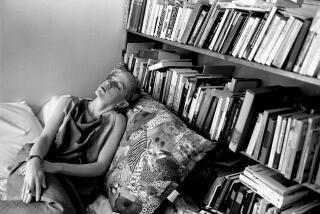

Cathy on the couch

This weekend marks the end of an era for American women. Cathy, the weight-obsessed, chocolate-loving, shopaholic comic strip heroine who has appeared in newspapers (including this one) for more than three decades, will make her final appearance on Sunday.

Cathyâs creator, Cathy Guisewite, has been chided for plenty of things over the years, not least sabotaging female progress by trafficking in hoary and reductive female stereotypes. The title character had a nagging mother, a fear of dressing rooms and a straight-from-the-container Haagen-Dazs response to all of lifeâs frustrations. Curiously, she didnât have a nose, but if she did, you can bet sheâd have longed for rhinoplasty.

In fairness to Guisewite, itâs no small thing to be counted among the first nationally syndicated female comic strip artists and, moreover, to do so with a character that was at least theoretically positioned to offer some insights into the lives of contemporary women. Cathy had a job, her own apartment and a rescue dog. Her debut in 1976 involved waiting for the phone to ring, but even with that start, she might have been running a company by 1986 or running for president a few decades later. Instead, Cathy remained a largely static figure.

Comic strip characters have a way of doing that, of course. (We donât really want to see Charlie Brown on antidepressants, though he could probably use them.) But as Cathy became a brand and her neuroses decorated clothing, mugs, calendars, mouse pads and other accessories for the home and cubicle, the strip came to be read as a kind of shorthand for the state of American womanhood, an invitation to join the sisterhood of chronically sad but ever hopeful âmodern gals.â

Does Homer Simpsonâs couch-potatodom makes him chief representative of âall menâ? Letâs hope not. If most men were like Homer, the world would screech to a halt. Somehow, though, Cathyâs binge eating and thigh-related anxiety werenât idiosyncrasies but, well, just the way women are: insecure, needy, periodically psychotic. (Cue the PMS joke.)

Cathy had ubiquity on her side; she was in the paper every day for all those years (there was even an Emmy-winning TV special in 1987). And her format required a punch line in four frames, which kept her on message and accessible. But more important, she tapped into something Homer couldnât: a supportive wave of murky, squirmy and highly popular womenâs media.

That behemoth, of course, is the realm of the Lifetime channel, âfem jepâ ( âfemales in jeopardyâ) movies of the week and Dr. Philâs entire career of hectoring âtherapy.â This is the genre that censures normal bodies while pretending to celebrate them, that pathologizes relationships while claiming to help heal them, that makes you feel like crap while offering you 10 tips on how to feel like a million bucks.

Cathy, with her custom blend of self-loathing and attempts at self-help, was a shoo-in for this sorority, an icon of the crabbiness-as-empowerment movement that the womenâs media cabal has been specializing in since roughly the 1970s. (Presumably, its let-it-all-hang-out M.O. was a reaction to the girdles and good behavior of pre-Betty Friedan America.) But in the end, to a lot of women (and men), Cathy â and her sweat pants, her co-dependency and her ceaseless expressions of need â somehow seemed more a casualty of the new regime rather than a beneficiary of it.

On the one hand, you have to hand it to Guisewite. She got rich in this bargain and, in fairness, the issues at the root of âCathyâ â workplace inequities, body image, the never-ending Mars/Venus communication breakdown â are not only personal but also potentially political in important ways.

But the apolitical Cathy never got there. She may have rid herself of the single-girl cliches (she eventually married, long after Guisewite did). But she never outgrew the cliche of woman-as-emotional-train wreck. Hers was a world in which sisterhood wasnât so much powerful as it was a club of shared misery. And that was not only totally unfeminist; it was totally unfunny.