THE WORLD : China faces reckoning over lead : Thousands have been sickened in a region where a cluster of factories processed the heavy metal for years.

- Share via

JIYUAN, CHINA — People in their 30s and 40s here complain of unpredictable senior moments: They go to the store and can’t remember what they wanted to buy, or they forget the names of old friends.

The children lose so much weight that they look like they’re shrinking instead of growing.

The leaves drop from the trees throughout the year -- not just autumn -- and the corn crop is stunted. Piglets are stillborn.

Now thousands of Chinese are trying to flee a landscape poisoned by decades of lead manufacturing. Within the next year, about 15,000 people will be evacuated from villages around a cluster of lead production facilities in the city of Jiyuan, in Henan province.

“What choice do we have?” said Han Haibo, a 51-year-old resident of Qingduo, a village of 1,000 that probably will cease to exist within months. “People don’t want to leave, especially the old people who have spent their whole lives here, but the pollution is just too heavy.”

Perhaps it is a sign of China’s coming of age that people are waking up to the dangers of lead.

China is the world’s largest producer and consumer of lead, but until recently its toxicity rarely entered the Chinese consciousness; in 2007, when millions of Chinese toys were recalled over lead in the paint, many people here grumbled that Americans were too fussy.

Now the Chinese are getting themselves and their children tested. And after finding shockingly high levels of lead in their blood, they are demanding action, in some cases rioting to get attention.

Since late summer, there has been a spate of lead poisoning cases in Hunan, Henan, Yunnan and Shanxi provinces. More than 3,200 cases have been confirmed, most of them in children.

The lead poisoning is so bad that at least 10 villages are being evacuated around Jiyuan, headquarters of the Henan Yuguang Gold and Lead Co., the largest lead producer in Asia.

“The Chinese people have had to learn that you shouldn’t make a profit by destroying the environment,” said Yuan Hong, a 56-year-old activist who is helping villagers.

Jiyuan lies 60 miles northwest of the provincial capital of Zhengzhou, along a highway lined by cornfields and factories -- power plants, metal works, chemical plants, textile mills. It still looks like countryside here, but the smell is more like the worst stretch of the New Jersey Turnpike.

Peering out at the landscape is like looking through a dirty windshield. Everything from the rosebushes to the withered squash drooping from vines in gardens is covered with a fine dust.

“When they let out the lead exhaust at night, there is this yellow smoke streaking the sky and a sick smell, kind of sweet,” said Zhang Zunbing, 34, whose village, Diantou, is about half a mile from the lead factory.

His year-old son was tested last month for lead poisoning and was found to have a blood count of 355 micrograms per liter. (Any level over 100 is considered dangerous for children.) The boy, Chenpeng, suffers from chronic diarrhea, nausea and nosebleeds, and his weight has dropped from 25 to 22 pounds in the last month.

“It is like my son is shrinking,” Zhang said.

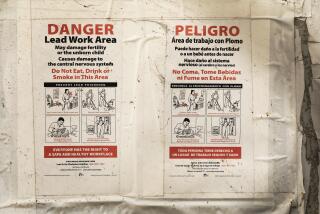

Children are most susceptible to lead poisoning because the dust from the heavy metal gets into the ground where they play.

They also suffer more from the consequences, as lead can cause developmental delays. The vast majority of the children in villages near the plant have elevated levels of lead in their blood, as do many adults.

According to the Jiyuan city government, 203 children are currently hospitalized for lead poisoning, and 115 have been treated and released. The local government has provided funds for treatment as well as extra money for fresh milk, which is believed helpful in reducing lead levels.

For the time being, production is suspended in 32 of 35 facilities for making electrolytic lead, a key ingredient in car batteries.

“The company is facing the reality and not avoiding its responsibility,” said Cai Liang, a spokesman for Yuguang, a 50-year-old company that trades on the Shanghai stock exchange.

The lead-poisoning story here doesn’t strictly follow the template of so many other cases of industrial pollution in China, with stock villains like greedy industrialists and corrupt politicians. Yuguang had a good reputation in Jiyuan, funding public buildings and sports, underwriting a women’s basketball team and providing jobs.

Lead was a boom industry in a rapidly industrializing country. As automobile use soared in China, so did demand for the electrolytic lead needed for batteries. The lead smelters in Jiyuan also imported ores to be refined into electrolytic lead and exported to the United States and Europe.

“We did the work that developed countries don’t want to do, making huge profits from a product that damages the environment,” said Li, a 41-year-old lead factory worker from Jiyuan who asked to be quoted only by his surname.

After he got out of the army in 1991, Li started working in the lead industry, first for Yuguang, later for another firm, Wanyang. He says he didn’t have much choice because the land in his village had been expropriated for smelters.

“We sort of knew it was dangerous, but the lead factories were the only ones that paid on time and provided stable work,” said Li, who made about $300 a month, almost double the wages at other factories.

He had a key job, separating lead from ore at the smelting stoves. Although factory workers were instructed to wear masks, they often removed them because it was difficult to breathe.

Li fell ill 16 months ago, spitting up blood and suffering from stomach problems. Standing 5-foot-10, he now weighs 130 pounds. He also complains of memory loss; he is constantly going out and then forgetting what he intended to do.

“It is like my brain doesn’t work anymore,” Li said.

But before it brought illness, the lead brought money. In the villages near the smelters, it is not uncommon to go down narrow dirt alleys and enter a home with nice tile floors, flat-screen TVs and leather sofas.

And despite their anger over their situation, many of the residents say they would leave the villages of their ancestors rather than force the factories to close.

“They will knock down our village and expand the factory and put us somewhere else,” Li said. “Maybe the old people won’t want to move, but the rest of us are happy to go.

“There is no reason to be sentimental about it. There is nothing on this land anymore -- even the grass doesn’t grow.”

--

Tommy Yang and Nicole Liu of The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.