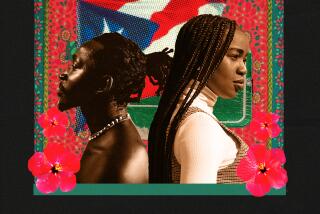

Two sides to Sonia Sotomayor

PRINCETON, N.J., AND WASHINGTON â It did not take long after moving 60 miles from the ethnically diverse neighborhoods of the Bronx to the campus of Princeton University for Sonia Sotomayor to make it clear she was not happy with the way the overwhelmingly white, male school was run.

In her sophomore year, Sotomayor walked into the office of university President William G. Bowen to demand more Latino faculty and students. Not satisfied with his response, she and others filed a complaint with the federal government, accusing the school administration of âan institutional pattern of discrimination.â

âThe facts imply and reflect the total absence of regard, concern and respect for an entire people and their culture,â she wrote in the Daily Princetonian.

Sotomayor, considered a brilliant student, graduated summa cum laude from the Ivy League school in 1976. While there, she was a passionate advocate for minorities and displayed an intense interest in her heritage: Her parents had moved to New York from Puerto Rico before she was born.

From Princeton onward, a look at her life has shown, she has viewed the law as a tool for social empowerment.

But critics of Sotomayorâs Supreme Court nomination fear that as a justice she would take that concern too far, siding with the underdog as a matter of principle rather than on the basis of cleareyed legal judgment.

âIt is perfectly appropriate for people to bring their life experience to their judging,â said John C. Eastman, a former clerk to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas who now serves as dean of the Chapman University School of Law in Orange. âBut thereâs a difference between having that perspective and being able to put one thumb on the scale to benefit one group over another.â

After Princeton, at Yale Law School, as a prosecutor and a corporate lawyer in New York, and while serving as a federal judge for 17 years, Sotomayor continued to display a passion for minority rights. She was active on the board of directors of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund when it sued New York City over alleged discrimination in police hiring and the drawing of voting districts, as well as when it challenged New York stateâs death penalty law.

Eight years ago, while sitting on the federal appeals court in New York on which she still serves, Sotomayor said it was âshockingâ that there were not more minority women on the federal bench.

But little of that activist sentiment is revealed in the hundreds of cases Sotomayor has decided in her 11 years on the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals, raising the question of which jurist will present herself if she is given the lifetime tenure and complete independence of a Supreme Court seat.

Thomas Goldstein, a Washington lawyer with a Supreme Court specialty, said last week that he had reviewed 50 appeals involving race in which Sotomayor participated. In 45 of those cases, a three-judge panel rejected the discrimination claim -- and Sotomayor never once dissented, he said.

âThis is a judge who does not see it as her job to fix all the social ills in the world,â said Kevin Russell, a Washington appellate lawyer who also has analyzed Sotomayorâs opinions.

But in her 1974 letter to the student newspaper, Sotomayor complained that the university had no faculty members of Puerto Rican or Mexican descent. The incoming freshman class that year numbered 1,141. Of those, 36 were Latino. The inequities she felt she confronted there cut her deeply, friends said.

In her junior year, Princeton tapped Sotomayor to serve on a student committee that advised the administration on replacing an outgoing dean dedicated to minority issues.

But she grew disillusioned with the assignment. She objected that her committee had little power to influence the selection. In a 1974 article in the Daily Princetonian, Sotomayor was quoted as saying: âWe were token students, period. The decision was made without consulting us.

âWhat we in effect want is for the school to realize weâre not here to play patsies, weâre not a front.â

On campus, she was active in Accion Puertorriquena, which served as a kind of social and political center for Latino students.

She spoke up for gays who were being harassed on campus. One of her public policy professors, Jameson Doig, recalls that she also spoke out against police abuse.

âPolice brutality was an area that was of greater concern to those who are familiar with poorer areas in New York. She was an articulate person in expressing concerns about that kind of misbehavior and in suggesting ways that one could reduce problems of police and public housing violence,â Doig said.

As a junior, Sotomayor helped design a course called âHistory and Politics of Puerto Rico,â which she described as a framework for evaluating the U.S. territoryâs problems.

She devoted her 169-page senior thesis to modern Puerto Rican history, conceding her bias in favor of its legal independence but asserting that her conclusions were based on her research, not her leanings. It was dedicated to, among others, her âhusband-to-be, Kevin -- for the love and supportâ and for teaching her âto approach life with an open mind.â

She and Kevin Noonan were married after graduation. They divorced seven years later.

âI donât know if she would have traded the Pyne Prize for anything,â said Sergio Sotolongo, a friend who went to Cardinal Spellman High School and Princeton with Sotomayor, who won the universityâs top undergraduate academic award in 1976. âBut I think in her heart of hearts, she would have wanted to see more change while she was there.â

Sotolongo, who was born in Cuba, said: âThe same issues Sonia pressed, we pressed as well: to get more faculty of color and more students of color. And after graduating, I can tell you, for the first five years I didnât want to go back.â

Sotomayor went on to Yale, where the environment was strikingly similar. She was one of a handful of Latinos in her law school class of about 160 students. There were slightly more African Americans. None of the 30 or so members of the faculty was Latino, one was black, and two were women.

âIt can be pretty intimidating,â said Stephen Carter, a black classmate who now is a Yale professor. âBut I donât think she was intimidated.â

Sotomayor immersed herself in the law -- and fused it to her Latina identity. For the Yale Law Journal, she wrote a treatise on how Puerto Rican statehood might affect the commonwealthâs mineral rights.

And as she had done at Princeton, she found ways to engage in advocacy. Instead of the ready-made support groups that Sotomayor found at Princeton, there were so few minority students at Yale that she could only join an umbrella organization of Latino, Asian and Native American students. She eventually became a co-chair, meeting with the law school dean and others about adding more minorities to the student body and the faculty.

Sotomayor was quietly forceful, not dogmatic or inflexible, her classmates said.

âWe did advocate for diversity. We did it together,â said Rudolph Aragon, who was a close friend of Sotomayorâs. âShe was not a radical. Iâve seen people try to portray her as an ethnic radical. She was far from that.â

But Sotomayor reached a breaking point over her heritage. Lawyers for a well-known Washington law firm made what she viewed as insulting remarks at a recruiting dinner, suggesting that Sotomayor was at Yale only because of affirmative action.

Instead of shrugging it off, she filed a formal complaint. Student groups quickly backed her -- and demanded that the firm be barred from recruiting on campus.

A faculty-student tribunal was convened to hear testimony, with Aragon acting as Sotomayorâs counsel. Two of the three faculty members, all white men, sided with the law firm against her -- something that stayed with her. The tribunal as a whole, however, ruled in her favor, and the law firm was forced to apologize.

But Sotomayor declined to return for another interview.

After earning her degree, she decided to go into public service as an assistant district attorney in New York.

Thirty years later, she is poised to go to Washington if the U.S. Senate confirms her, making her the first Latina on the Supreme Court.

--

Times staff writer Tina Susman in New York and Andrew Zajac in the Washington bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.