The rubber meets the road

Chastised by lawmakers and President-elect Barack Obama last month for not offering enough rationale for a federal bailout, the Big Three automakers returned to Washington this week and asked for even more money. They replaced their previous request -- $25 billion in low-interest loans and credit lines -- with an increasingly desperate-sounding bid for $34 billion in aid. At the front of the line stood General Motors, which warned that it would fail very, very soon unless it received $12 billion in loans within the next few months. Chrysler said that it too could go belly up by the end of the year.

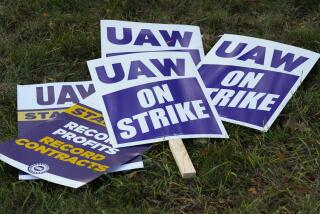

Along with their supplications, the carmakers promised to make changes to the way they do business. These ranged from the purely symbolic, such as eliminating chief executives’ salaries, to the painfully substantive, such as dumping entire brands and thousands of dealerships. The latter points to the cold, hard facts of the situation: Unless the Big Three produce and sell cars more efficiently, they won’t have any hope of ending a three-decade slide in market share.

But efficiency is just part of the problem, and it may be the least difficult to solve. After all, the three companies have made great strides in recent years in narrowing several of the performance gaps between their factories and those operated here by foreign automakers. There’s little difference these days in the average wages paid and benefits offered to new employees, or in the time spent producing each car. Nor do large gaps remain in quality, reliability and innovation.

Today, the biggest challenges for the Big Three are their top executives’ insularity and sense of self-importance, the public’s perception that their products are inferior and the recession that’s sapping demand for cars. The first two could be addressed by sweeping out the current management and declaring a fresh start, as Chrysler did when it brought in Lee Iacocca to rescue the company (with the help of federal loan guarantees) in the late 1970s. Iacocca not only brought out products that matched the new demands of the market, as the Big Three are rushing to do today, but he convinced people that Chrysler had fixed its quality problems. He had the credibility his predecessors lacked, even though some of those new products weren’t that much of an improvement.

The recession’s effect on car buying poses the thorniest issue for policymakers, but it also supports Detroit’s case for temporary help. When even Toyota’s and Honda’s sales drop by a third, it’s clear that there are endemic troubles beyond the industry’s control. It’s also apparent that no matter which way Detroit goes -- bailout, bankruptcy protection or liquidation -- taxpayers are going to be on the hook for billions of dollars, given the unwillingness of private lenders to take on the risk and the massive liabilities for workers’ pensions. We think there would be less pain caused by restructuring into smaller and more efficient units without dipping into liquidation. What’s still missing is a plan that forces the Big Three to make specific improvements -- not only to raise their efficiency and competitiveness but also to restore the public’s elusive confidence in their brands.