Caltech geneticist linked DNA, aging

- Share via

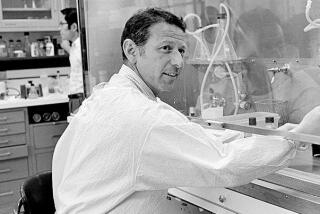

Dr. Giuseppe Attardi, the Caltech geneticist who played a key role in illuminating the function of mitochondria and linked mutations in mitochondrial DNA to the aging process, has died He was 84.

Attardi died Saturday at his home in Altadena, Caltech announced without specifying the cause of death.

Mitochondria are tiny organelles within every cell of the body that convert the energy in food into a form of chemical energy, called adenosine triphosphate, that can be used by the cell.

They thus provide the energy for everything from whacking a tennis ball to contemplating the nature of the universe. Until the work of Attardi and others in the 1960s and 1970s, however, little was known about how they functioned.

It was known that mitochondria were the only sites outside the nucleus of the cell that contained DNA, the genetic blueprint for life. This DNA is inherited only from the mother, and researchers now often use it to trace the genetic history of individuals and groups.

Attardi was the first to show that mitochondrial DNA, also known as mtDNA, was functional, producing messenger RNA that was used to manufacture proteins.

He isolated and identified the messenger RNA that was produced from each of the 37 mitochondrial genes and the proteins that were produced from it, said Caltech biologist David Chan, his friend and colleague. He showed “what the products of the mitochondrial genome were,” Chan said.

Attardi also played a crucial part in showing how mutations in mtDNA contribute to disease. Before his work, it was impossible to separate the contributions of such mutations from those of mutations in nuclear DNA.

He developed a technique for stripping all of the mtDNA out of a healthy cell, then replacing it with the corresponding DNA from cells of a sick patient. He could then determine how the mutations in mtDNA affected the functions of the cell.

In this way, he was able to show that a rare form of dementia now known as MELAS syndrome -- or mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes -- was in fact caused solely by mutations in mtDNA.

Other researchers have subsequently used the same technique to prove that a variety of other congenital disorders are also produced by mutations in mtDNA.

Over the years, researchers have speculated that declines in the functioning of mitochondria over time leading to a decline in the chemical energy available to cells might be responsible for many of the effects of aging.

In 1999, Attardi and his colleagues at Caltech and the University of Milan demonstrated that mtDNA from the elderly contains mutations that are not present in younger people, suggesting that changes at these DNA hot spots may be the cause of loss of function.

The results suggest that aging of the cell begins within the mitochondrion.

In 2003, Attardi found that a rare inherited mutation in mtDNA is associated with a longer life. This mutation may provide a survival advantage by speeding the replication of mtDNA, allowing aging cells that carry it to produce more energy than those who do not.

Giuseppe M. Attardi was born Sept. 14, 1923, in the small town of Vicari, Italy, in the province of Palermo on Sicily. Although he was in Italy during World War II, he avoided being drafted into Mussolini’s army because he was in medical school at the University of Padua, where he received his degree in 1947. He remained on the faculty there for 10 years. As a Fulbright Fellow, he also spent time at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm and the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

He joined the staff of Caltech in 1959 and remained there for the rest of his career, running a productive laboratory until last summer. He became a U.S. citizen in 1974.

According to his wife, Anne Chomyn, he was interested in art and in classical and ethnic music. In his younger years, he was an avid mountain hiker. He climbed Mt. Whitney as late as the 1970s, she said, and the couple hiked the Alps in the 1990s.

“One of the things I will always remember about him was his constant excitement for all types of biological questions,” Chan said. “I think his intense curiosity was one reason he accomplished so much as a scientist.”

Biochemist Gottfried Schatz of the University of Basel’s Biozentrum in Switzerland added that Attardi “embodied a vanishing breed of scientists whom I would define as ‘gentlemen intellectuals.’ ”

“He had a superb grasp of European history and world culture, had mastered French and German at a very high level of proficiency and even in his most spirited discussions refrained from personal invective or overt aggression,” Schatz said.

In addition to his wife, a senior research fellow emeritus at Caltech, Attardi is survived by a son, Luigi, of Rome; a daughter, Laura Attardi of Palo Alto; and a grandson.

Services will be private.

--