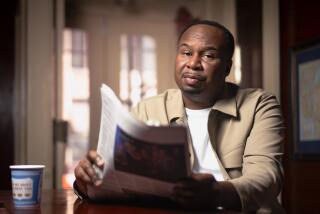

Good ol’ Charlie, our favorite anchor dad

Charlie Gibson this week officially occupied the anchor desk on ABC’s “World News Tonight,” becoming Charles Gibson in the process but otherwise remaining recognizably himself. Other anchors have kept their nicknames when they took the job: Tom Brokaw was never Thomas, nor Dan Rather Daniel, nor Bob Woodruff Robert, in his brief term. (Will Katie Couric be Katherine at CBS?). But Gibson is running against the additional weight of his congenital boyishness, his regular-guy demeanor and an all-purpose cheerfulness burnished over nearly two decades in the daddy chair of “Good Morning America,” which required him to seem terrifically interested in anything at all. He is a Princeton graduate who has interviewed several presidents of the United States, but he does look like one of the junior Waltons.

The anointing of a network nightly news anchorman is news itself if only because it happens so rarely: They are chosen less frequently than presidents -- Peter Jennings was the ABC anchor for more than 20 years and would be there now if death hadn’t intervened -- and, indeed, of all jobs in television it is the most presidential, a position both real and symbolic. The anchorman stands not just for his particularly corporate nation-state but for his constituents, his viewership; he represents them to the world, just as he represents the world to them. He must be a coolheaded voice of reason when all around, including actual presidents, are losing theirs -- their cool, their heads, their reason -- or a hurricane hits, or something blows up.

And like the presidency, it is not just a job you do, but a part you play. It’s not to question the journalistic bona fides of Gibson or any of his colleagues to say that their hiring is first and foremost a casting decision, just as a TV news program is first and foremost a television show, one that earns its keep in just the same way as do “Two and a Half Men” and “American Idol.” At the same time, the part dignifies the actor: Some presidents were doubtless presidential in the cradle, just as some anchormen may have sucked pacifiers and shaken rattles with precocious dignity, but in each case, the job bestows some kind of gravitas on the holder, although, as we have seen, it can’t work miracles.

There is always the question with a new anchor of whether (1) he or she is sufficiently within the tradition to deliver something as important and serious as the evening news and (2) whether he or she departs enough from the tradition to draw the younger audiences the old media are losing to the new. It’s important to be both different and not too different. And there is here the corollary question of whether Gibson, like Couric, is so identified with the burble of the morning shows that audiences will not be able to credit him seriously as an evening newsreader, but that issue’s a non-starter, dispensed with in two words: Tom Brokaw.

The fact is that the distance between the morning shows and the evening news is not as great as all that, a matter of emphasis rather than kind -- each mixes the hard and the soft -- just as the dad who plays catch with you in the morning is the same dad telling you to take out the trash at night. Gibson, who is hanging around “Good Morning America” through the end of June, has been doing double duty and has been equally convincing dealing with matters of war and with the amount of money you can save using coupons to dine in New York restaurants.

Gibson is not a new broom sweeping clean but a mark of continuity in a time of unasked-for change -- an old broom sweeping some of the dust back in to keep things cozy. As Gibson himself put it on his first-night sign-off, “I don’t know if I’m a new old face or an old new face on this broadcast.” On some level, the choice seems counterintuitive: He’s 63, nearly two decades older than the two anchors he’s replaced -- Bob Woodruff, recovering from a roadside bombing in Iraq, and Woodruff co-anchor Elizabeth Vargas, who could not hold the ratings and is leaving under cover of pregnancy. He’s a mark of solidity, which is not to say stolidity, in a time when the biggest question in TV news is how to create a new audience, not just hang on to the shards of the rapidly thinning old.

Since the anchorman proves his mettle and writes his legacy in extraordinary circumstances, those moments when he must think on his feet and feel for the nation, there’s not much to say about Charlie yet. (He may be Charles in the credits, but he’s still “Charlie” to the correspondents who address him from the field.) He isn’t dashing like Jennings, or a flak-jacket reporter like Dan Rather, where Woodruff -- globe-trotting, multilingual, embedded -- was a bit of both. He’s likable without having to work at it and communicates an air of capability, like an early Ford, and the sense of being a team player. One imagines he’d be a good dinner guest, that he wouldn’t dominate the conversation, even though his stories would be better than anyone’s, and that he’d help with the dishes afterward.

His signal quality, I think, is a kind of egolessness. You don’t become an anchorman without some sort of ego, of course, but still one feels -- and it’s only a feeling, but that is how we choose between anchorpeople, since they all deliver more or less an identical product -- that he never coveted the job and that even now that he’s got it, it’s something he could walk away from. (And there does remain the open question of what happens when Bob Woodruff gets better.) It’s exactly the quality one wants in a president, and rarely gets.